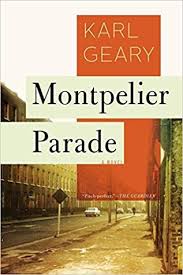

Karl Geary’s first novel, Montpelier Parade (217 pages; Catapult), presents us with the fraught experience of first love, told in beautifully doleful prose that sometimes exhibits Salinger-esque sparseness. Referring to his protagonist, Sonny, as “you,” Geary draws the reader into a hypnotic and haunting intimacy. The directness of the second-person point of view demands both Sonny and the reader are left weary by the cloudy Dublin skies and by the “howl of feeling.” It’s a delicate work that treats its subject with great sensitivity, ensuring we experience that same tenderness of feeling that Sonny does, and hear the words on the page like the brutally honest voice of a friend.

Karl Geary’s first novel, Montpelier Parade (217 pages; Catapult), presents us with the fraught experience of first love, told in beautifully doleful prose that sometimes exhibits Salinger-esque sparseness. Referring to his protagonist, Sonny, as “you,” Geary draws the reader into a hypnotic and haunting intimacy. The directness of the second-person point of view demands both Sonny and the reader are left weary by the cloudy Dublin skies and by the “howl of feeling.” It’s a delicate work that treats its subject with great sensitivity, ensuring we experience that same tenderness of feeling that Sonny does, and hear the words on the page like the brutally honest voice of a friend.

Sonny is a pitiful Irish teenager growing up on the decaying outskirts of Dublin. He longs to escape from the drab confines of his father’s expectations, his mother’s depression, and the mindlessness of his TV-consumed brothers. More than any of this, he longs to feel a sense of belonging and the soft embrace of a devoted lover. He is so alone he seems afraid of being noticed. A quiet and keen observer, Sonny breaks the reader’s heart in the most banal of ways. The moments of tragedy in Sonny’s life are delivered in the same quietly devastating manner as his mundane experience: the novel begins with the accidental death of a drunken man leaving the butcher shop at which Sonny works and ends with the suicide of a character he literally worships, yet Sonny reacts as though these events are no more momentous than the stale loaf that rests forgotten on his kitchen counter. All too accustomed to pain from every direction in his life, Sonny appears to regard suffering as both inevitable and unavoidable. All the while, his hunger for love proves so fundamental one wishes to somehow feed him. For Vera, the older woman who becomes both his secret lover and the hope he is terrified to possess, continues to deny Sonny––for she, too, is frightened by her own desperate need.

And so Sonny is left in that space between longing and pursuit, kept company by a slight boredom, the hum of the refrigerator, and the rustling of spiders. When he’s not in the shed fixing his bike with stolen parts or working at the butcher’s shop, he’s usually with his friend Sharon at the Cats’ Den. Sharon, the girl whose punches “hurt and were lovely and a comfort” and who’s been everybody’s girlfriend, shares her cigarettes with Sonny and follows him to the museum even when he’s thinking of Vera. It is Sharon who reminds him of the world he is expected to belong to, the everyday world his mother inhabits. Walking arm and arm with Vera, at one point, Sonny sees his mother struggling with the pull of “four or more plastic bags…like demanding toddlers,” but he never breaks his stride. He only turns to look back once she becomes a shadow, and is ashamed by his betrayal of the woman who raised him and never hugged him back. By the time Sonny’s two worlds collide––the world he lustfully imagines and the one that comprises his waking life––Montpelier Parade leaves us as it leaves Sonny, pondering how life can be both empty and full at once.