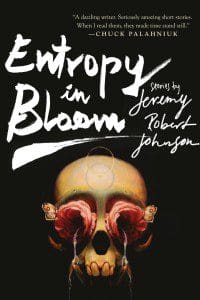

It’s the rare writer who is able to straddle the line between literary and horror fiction. For every author like H.P. Lovecraft and Shirley Jackson who has since been adopted into the canon, there are countless others who remain on the outskirts of the literary scene. Of course, working in the fringes of any genre allows one to take creative risks and make provocative choices. Readers who find themselves drawn to the new story collection Entropy in Bloom (252 pages; Night Shade Books) by Portland writer Jeremy Robert Johnson will likely believe that the author has indeed gotten away with something.

It’s the rare writer who is able to straddle the line between literary and horror fiction. For every author like H.P. Lovecraft and Shirley Jackson who has since been adopted into the canon, there are countless others who remain on the outskirts of the literary scene. Of course, working in the fringes of any genre allows one to take creative risks and make provocative choices. Readers who find themselves drawn to the new story collection Entropy in Bloom (252 pages; Night Shade Books) by Portland writer Jeremy Robert Johnson will likely believe that the author has indeed gotten away with something.

One of the pleasures of reading any collection that culls together stories produced over a span of time is witnessing a writer’s preoccupations and obsessions emerge on the page. With stories written between 2004 and 2011, Entropy in Bloom reads like a tableau of Johnson’s pet themes. Despite their Lovecraftian titles, stories such as “When Susurrus Stirs” and “Cathedral Mother” explore Johnson’s fascination with the way microscopic entities like parasites and tapeworms can alter human physiology for their own purposes. The idea of an invisible passenger in our bodies (“…I imagine the fibers of my spinal cord stretching out towards him like feelers”) has long been a potent theme in the genre, particularly in the body mutations conjured by filmmaker David Cronenberg, but in these tales Johnson tends to go for the gross-out rather than generate the lingering psychological effect of the best literary horror.

Far more interesting are the numerous stories, including the novella The Sleep of Judges, which examine masculine identity in our post-modern society. “Trigger Variation” offers a terrifying glimpse into the world of the EndLiners, a fictional group of straight-edge fitness junkies whose philosophy sounds not unlike many in the so-called Alt-Right movement—despite the fact that the story was written a decade ago. “The strongest beasts crush the weak. They consume without sentiment. They conquer!” their leader Frank shouts to pump them up before an organized pillow fight in a public park, a fight in which their pillow cases will be filled with wrenches, hammers, and other assorted weapons. “The laziest of beasts are slaughtered and those that struggle must survive!” The story’s vision of the EndLiners and their promotion of an ideology that “freed them from believing in the nobility of anyone other than themselves” read as all too real in the wake of recent clashes between far-left and far-right protestors in cities like Johnson’s own.

Elsewhere, Johnson probes the conflicts that arise in the wake of burglary and theft, particularly what personal violations such as being robbed or violently accosted do to the mental state of his male protagonists. In “A Flood of Harriers,” a liberal-leaning couple on their way to Burning Man finds their relationship strained after a knife attack on the outskirts of a reservation: “You looked so scared,” the narrator’s girlfriend tells him. “You just didn’t look like the guy I thought I knew.” This revelation causes him to break down and seek revenge, in a manner that recalls Dustin Hoffman in Sam Peckinpah’s controversial 1971 film Straw Dogs.

In The Sleep of Judges, the longest and possibly strongest piece in the collection, main character Roger returns home from a birthday party to find his family’s house has been burglarized. The resulting stress sends Roger down a rabbit hole of paranoia and insecurity, such that—even when a supernatural menace is uncovered in the neighborhood—the real terror is the increasingly dire lengths Roger proves willing to go to fortify his home and “protect” his family. (There is also a question of just how much of his fervor remains rooted in his jealousy of a rugged neighbor who flirted with his wife at the party.) Arriving at the scene of the crime, a cop observes the lack of locks on Roger’s windows and states, “You were so easily penetrated.” His remark continues to reverberate in Roger’s skull for the entire story. As Johnson himself admits in his Author’s Notes: “If you’ve ever been burglarized…then you know the theft is just the very beginning of a long and unsettling road.”

While it’s rewarding to witness Johnson return to his favorite themes throughout Entropy in Bloom, his writing often proves more interesting when he heads in unexpected directions: “States of Glass” follows a woman’s complex array of emotions upon learning her husband might have been killed in an auto accident, including her intense attraction to the coroner in the moments before she is showed a glimpse of the body that may or may not be her spouse (“…I don’t want to understand this experience. I just want to smash it away”).

Most tender and surprising is likely “Swimming in the House of the Sea,” a painful slice-of-life story about a twenty-one year-old college dropout poisoned by bitterness after witnessing his parents’ divorce and being forced to supervise his mentally-challenged younger brother. He allows that bitterness to taint his interactions with everyone around him: “Aggression without reason is a bit of a stress reliever in itself. Let somebody else absorb the shit I’ve been through today.” During a stay at a rundown motel in Bakersfield, a chance encounter with a middle-aged father whose son faces his own developmental challenges delivers the narrator some unexpected clarity, displaying that even in a story collection full of flesh-rendering parasites and supernatural prowlers it’s man who proves capable of the most cruelty, and any bout of grace must be hard-won.