It’s that time of year when some people hit the beach while others hit the bookshelves. Here’s a look at what the ZYZZYVA team has been reading these last few months in order to beat the “heat” of summer in San Francisco:

It’s that time of year when some people hit the beach while others hit the bookshelves. Here’s a look at what the ZYZZYVA team has been reading these last few months in order to beat the “heat” of summer in San Francisco:

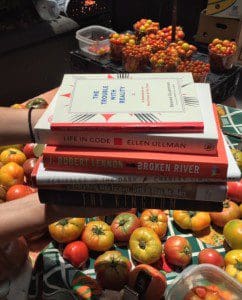

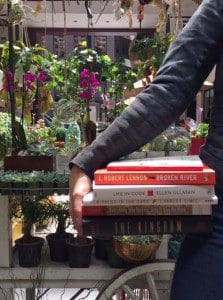

Laura Cogan, Editor—What is it about summer that makes a thriller especially enticing? Is it the contrarian in me, looking perversely for some shade to counteract the sunny aesthetic of the season? There may be some anecdotal evidence to support this theory, at least in my case: I was visiting the preternaturally well-appointed Marin Country Mart a few weeks ago—a place radiant with fine weather, fresh produce, happy children, and an overall sense of well-being—when I stopped in at DIESEL, and left an hour later with several fairly dark titles.

J. Robert Lennon’s Broken River (Graywolf Press) is a terrifically satisfying entry in the too-often elusive category of literary thriller. As with any good thriller, the plot is propulsive—but, as with any work of literary fiction, the plot is also, ultimately, not the most intriguing or memorable aspect of the book. The murder mysteries of Broken River are layered with mediations on narrative and storytelling, including a wonderfully eerie, developing entity Lennon calls the Observer. Brooke Gladstone’s slim nonfiction volume The Trouble With Reality (Workman) is subtitled “A Rumination on Moral Panic in Our Time”—a predictably seductive framing to those of a certain mindset in this summer of 2017. It’s a slight book, both in heft and in depth (after all, there is much, almost too much, to be said on the subject), but it does offer a pleasingly pared-down distillation of important ideas—chief among these the concrete threat that the lack of a shared reality (or, put differently, lack of agreement on “the terms of the debate”) poses to the basic functioning of democracy. I enjoyed having it in my purse for a week, and found myself reading a few pages while commuting or waiting in line rather than looking at the news on my phone—a most welcome change. It was Charles Simic’s latest collection, Scribbled in the Dark (Ecco), however, that spoke most directly to my troubled mind in this uneasy season. “All Things in Precipitous Decline” is the perfect title of one especially perfect poem. Each exquisite poem seems to inhabit the same haunted village, and the characters and ghosts and abandoned courtrooms and libraries and stray dogs all have the sense of both a memory and a premonition. And now, as July draws to a close, I’m looking forward to Ellen Ullman’s Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology (MCD/FSG, August 8). I’ve been anticipating this collection of essays reflecting on technology and culture for ages. In the meantime, I’m dipping back into my long-term reading project: Musil’s The Man Without Qualities. Which, with its arch interrogation of the decay of culture and society leading up to World War I, feels only superficially ill-suited to the literal season, while astonishingly, painfully relevant to the political and cultural season.

Libbie Katsev, Intern—In Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation, UC Berkeley anthropologist Alexei Yurchak explores why Soviet citizens found the USSR’s collapse both unthinkable and inevitable. Hoping to avoid the binary thinking that dominates language about the Soviet Union, (“official public” and “hidden intimate”; “truth” and “falsity”), Yurchak analyzes interviews, personal writings, jokes, newspaper articles, speeches, and more to examine the paradoxes of late socialism in the words of those who lived it. Though academic, Yurchak’s lively prose and vivid anecdotes make this ethnography an entertaining as well as illuminating read.

Aya Kusch, Intern—W.S. Merwin’s final collection of poems, Garden Time (Copper Canyon Press), offers new insights into the classic Merwin themes of loss, aging, memory, and the beauty of the natural world. In this conclusion to his extensive body of work, there is a comforting consistency to his voice, which maintains both a lyrical quality and lightness no matter how difficult the subject matter. His poetry is not so much about a surrender to the passage of time as it is an acceptance of it, even as life’s harsher aspects inevitably ebb and flow. Despite his impending blindness and the loss of loved ones, Merwin never gives way to a sense of bitterness. Rather, Merwin praises the serenity of the moment, while expressing a deep gratitude for the cherished memories that remain meaningful in the face of their growing distance.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant—When French author and filmmaker Emmanuel Carrère collaborated on the acclaimed television show The Returned, about a small mountain town in which the dead return from the grave and try to resume their prior lives, his thoughts kept returning to the Apostle Paul and his expectation that the deceased would one day be called back to life for judgment day. His musings led to The Kingdom (FSG) — part memoir, part fictional interpretation of the early Christian church, this conversational novel imparts Carrère’s varied thoughts on art, life, and love in that charmingly droll and erudite way that seems intrinsically French. Whether comically discussing his children’s nanny and her resemblance to Kathy Bates in Misery, or espousing his love of all things Philip K. Dick (“the Dostoevsky of our time”), Carrère’s voice registers as warm and intimate as a close friend. At the book’s heart is a man grappling with the illogic of his beliefs in an age that has traded faith for reason.

Samara Michaelson, Intern—I keep returning to James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Of all the novels I’ve read this summer, this is the book I’ve been most keen on savoring. I enter it like a dimly lit room. It’s not as though most people are unfamiliar with Joyce’s canonical work, but this year I find myself cracking the door to see how much of myself I can fit in it. I like to travel into all those dark little crevices that Joyce is such a master at shining just a touch of light upon, so that one may see but never touch. As in Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, there is a certain tenderness that accompanies the often melancholic and agonizing candor of a mind consumed by itself, as we see with the character of Stephen Dedalus. Jocye’s semi-autobiographical antihero seems to lead a life that is at once lonely and yet full. Full of what, I’m still figuring out. Everything is plainly there — but how can it be translated? Joyce makes me wonder at the immensity of life and just how much of it is unreachable through language. He crafts his web of words stitch by tiny stitch, though he utilizes this fabric to point to something that cannot be grasped, for to grasp it would be to obstruct its truth, to spoil its inherent intimacy. Maybe it’s the difference between feeling and knowing, and only an artist can stun you with the conviction of feeling.

Samara Michaelson, Intern—I keep returning to James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Of all the novels I’ve read this summer, this is the book I’ve been most keen on savoring. I enter it like a dimly lit room. It’s not as though most people are unfamiliar with Joyce’s canonical work, but this year I find myself cracking the door to see how much of myself I can fit in it. I like to travel into all those dark little crevices that Joyce is such a master at shining just a touch of light upon, so that one may see but never touch. As in Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, there is a certain tenderness that accompanies the often melancholic and agonizing candor of a mind consumed by itself, as we see with the character of Stephen Dedalus. Jocye’s semi-autobiographical antihero seems to lead a life that is at once lonely and yet full. Full of what, I’m still figuring out. Everything is plainly there — but how can it be translated? Joyce makes me wonder at the immensity of life and just how much of it is unreachable through language. He crafts his web of words stitch by tiny stitch, though he utilizes this fabric to point to something that cannot be grasped, for to grasp it would be to obstruct its truth, to spoil its inherent intimacy. Maybe it’s the difference between feeling and knowing, and only an artist can stun you with the conviction of feeling.