In Lima, Peru, in 1904, two wealthy young men wrote a letter to the Spanish Nobel Laureate poet Juan Ramon Jimenez, entreating him to send them a copy of his new book of poems. The young men believed the poet would be more likely to write back if they pretended to be a beautiful young woman. To their surprise, their joke backfires in an explosion of emotional shrapnel.

In Lima, Peru, in 1904, two wealthy young men wrote a letter to the Spanish Nobel Laureate poet Juan Ramon Jimenez, entreating him to send them a copy of his new book of poems. The young men believed the poet would be more likely to write back if they pretended to be a beautiful young woman. To their surprise, their joke backfires in an explosion of emotional shrapnel.

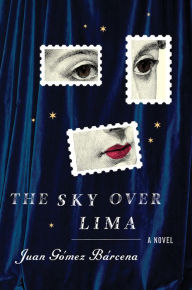

Based on this true story, Spanish author Juan Gómez Bárcena makes his literary debut with The Sky Over Lima (translated by Andrea Rosenberg; 288 pages; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), the charming retelling of a hoax that occurred a little over a hundred years ago. The novel’s satirical charm and witty re-creation of historical events take us into its embrace, but more than that, Barcena never allows us to forget that this story is, like our own lives, an artistic creation.

The men behind the letters are Jose Galvez and Carlos Rodriguez. Jose comes from a family with a well-known aristocratic name and even better known wealth, while Carlos’s father made his money in the recently developed rubber business. They fancy themselves bohemian poets, renting a room in an old apartment, living among immigrants and dockworkers while they write their puerile lines. Aware their writing is insipid, Jose and Carlos are nonetheless determined to throw tradition back in the faces of their fathers, rejecting the fates their families hold for them. They believe that by writing to the Maestro, whom they worship as a romantic figure and a true artist, they will learn the secret to being great poets.

But first they create Georgina, the imaginary woman who is to become Jimenez’s muse. Through her, they craft hopeful, perfumed letters and are astounded to receive a reply from the celebrated author. Their ecstasy is written into the next letter and the next, and eventually they weave themselves deeper into the deception. But there is a limit to their knowledge about women, which of course makes it difficult to write as one. Soon they are lead to Cristóbal, a notary who has written love letters for every person in Lima for years, and who is able to advise them in matters of courtship and seduction.

At this point, the pair starts to diverge in their opinions concerning the letters. Jose is more preoccupied with being called a writer than with writing. And Carlos, the more sensitive of the two, has fallen in love with their creation. The struggle with their desires and ambitions is complicated by their search for masculinity and understanding their place in the world—all of which is reflected in not only the novel but in the letters they write as Georgina.

Bárcena has an incredible voice, and The Sky Over Lima evinces the attention to detail and characterization of a Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The narrative paints the past, present, and future on the same canvas, adding to the novel’s theme that reality is created and that “everyone’s lives are literature.”

As the story reaches back into the young men’s upbringing to show how they have become the men they are today, and it also reaches forward to cheekily play on current events that have a deep connection with Latin America’s cultural history. In one instance, Bárcena writes that Carlos, who is arguing with Jose, would like to quote Foucault and Lacan to prove to Jose that “the entire world is a text constructed of words alone” but sadly cannot because neither scholar has not been born yet. In another scene, we see Jose as a young man in his father’s house, in love with the indigenous maidservant who takes his virginity and who will be preserved in Jose’s mind as the image of Georgina.

This is what keeps The Sky Over Lima from becoming just another charming historical novel—the grand Brechtian gesture with which Bárcena treats the narrative. As the story unfolds, the narrator explains how the story is being told, how the characters or the scene is being constructed. In one of the later chapters, Carlos visits a brothel and drunkenly follows one of the girls up to her room. Here Bárcena takes a moment to point out that she lacks the “discreet beauty of secondary characters, designed to entertain for a single chapter and then disappear without a trace. Perhaps aware of her modest role in Georgina’s novel, she doesn’t even open her mouth.” In another section, Carlos reflects on the letters he has written as Georgina, which number 249 pages. This reflection delightfully appears on page 249 of the book, another playful reminder of the interwoven nature of reality and fiction.

The novel is self-aware, revealing the scaffolding of its structure just as its characters are set in motion. The result is refreshing, breathing new life into a story and utterly revolutionizing it. For just as we are getting caught up in the action, the narrator will reveal himself again, pointing out with such perfect timing so as not to spoil the momentum of the book that the plot, though based on a true story, is a fabrication.

These reminders waver dangerously close to occurring too often, perhaps becoming kitschy or overstated for some. But the charm of the story and of the characters, and the ultimate illumination that floods Carlos and Jose at the end, tying all the meta-references together in service of the novel’s central them, make these risks forgivable.

The Sky Over Lima is a magician’s conjuring through which we are made to see our own artifice. As Cristóbal says to Carlos over drinks, placing a hand on the young man’s shoulder, “Open your eyes, my friend; love, as you understand it, was invented by literature, just as Goethe gave suicide to the Germans. We don’t write novels; novels write us.”