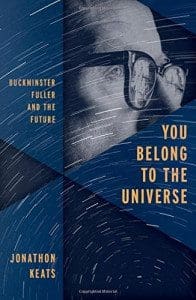

This Thursday at 7 p.m., author (and ZYZZYVA contributor) Jonathon Keats will be at City Lights to discuss his newest book, You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future (Oxford University Press). Called by Douglas Coupland a “wonderfully written and highly necessary book about one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic outliers,” the book takes Fuller’s life and personal myth as a basis for applying his world-changing ideas in the present.

This Thursday at 7 p.m., author (and ZYZZYVA contributor) Jonathon Keats will be at City Lights to discuss his newest book, You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future (Oxford University Press). Called by Douglas Coupland a “wonderfully written and highly necessary book about one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic outliers,” the book takes Fuller’s life and personal myth as a basis for applying his world-changing ideas in the present.

The following is an excerpt from Keats’s book.

Late one evening in the winter of 1927, Buckminster Fuller set out to kill himself in frigid Lake Michigan. At thirty-two years old, he was a failure. He had neither job prospects nor savings, and his wife had just given birth to a daughter. A life insurance policy, bought while he was in the Navy, was all that he had to support his family.

So Fuller walked down to a deserted stretch of shoreline on the North Side of Chicago. He looked out over the churning water and calculated how long he’d need to swim before succumbing to hypothermia. But as he prepared to jump, he felt a strange resistance, as if he were being lifted, and he heard a stern voice inside his head: “You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the universe.” Then the voice confided that his life had a purpose, which could be fulfilled only by sharing his mind with the world, and that his family would always be provided for, as long as he submitted to his calling.

He went home and told his wife. He explained that he no longer needed a job. He said that he had to think, and would not utter a word until he knew what he truly thought. For two full years, Fuller was silent. He filled five thousand pages with notes, as if in a trance. His jottings and sketches revealed the secret to making the whole human race successful for all eternity. He spent the rest of his life openly sharing the secret with everybody.

At least that’s how he later characterized his 1927 transformation, addressing lecture halls crowded with disciples listening to his wisdom for seven or eight hours at a stretch. Sometimes he changed details, such as whether his daughter was born before or after his lakeside epiphany, or the number of years he was silent, or how many pages he’d written. In interviews he might embellish his tale, claiming that he’d slept just two hours each night, or become a vegetarian, or moved his family into a slum where the neighbor was an Al Capone henchmen. Such details could easily be adjusted because even the essentials of his tale were essentially invented.

Scrutinizing the copious records he kept of his life—a 45-ton archive that he dubbed the Dymaxion Chronofile—scholars have found no evidence of a suicide attempt, or even a change in diet. Fuller did lose his job shortly after his daughter was born, but he found work within months. He became an asbestos flooring salesman, hardly a silent profession. Nonetheless, his files contain hundreds of pages of notes from the late ’20s, and the notes show that he was conceiving the philosophy and technology that would later mark his career as a self-proclaimed comprehensive anticipatory design scientist, distinguishing him as the inventor of the Geodesic Dome and the man who coined the term Spaceship Earth. During this period—as he started lecturing, and self-published his first book—he also began the process of crafting a personal myth.

The myth became more elaborate with repetition. It also grew more important as a narrative that illustrated his ideas and revealed linkages, rendering his worldview more intelligible to the broad public he sought to convert. Given his ambition of making the whole human race successful for all eternity, comprehensive anticipatory design science necessarily drew on bodies of knowledge as disparate as architecture, cartography, biology, economics and cosmology. His life story helped to unify these fields for his audience.

And also for himself. Every time he recounted his myth, Fuller reformulated his vision, combining his ideas differently with each variation. Self-mythologizing was his way of thinking. Autobiographical fraudulence afforded intellectual flexibility.

He was too priggish to admit it. He insisted that he was being completely forthright. Time and again, he advertised his openness by dramatically confessing his suicide attempt, and justified his candor by modestly describing himself as a human guinea pig. His life was “an experiment to discover what the little, penniless, unknown individual might be able to do effectively on behalf of all humanity”. The man who’d stood on the shore of Lake Michigan could have been anyone. Everybody could succeed as he had done, if only they embraced his beliefs and belonged to the universe.

In Fuller’s telling, every experience is essential because all knowledge is interconnected. His personal myth is the epitome of comprehensivism. Fuller didn’t need literally to stand by the lakeside in 1927—let alone spend the following two years in silent contemplation—for his vision of total global commitment to motivate audiences. “It’s a poet’s job he does, clarifying the world,” observed the literary critic Hugh Kenner. In his lifetime, Fuller was poet laureate of Spaceship Earth. There has not been one since.