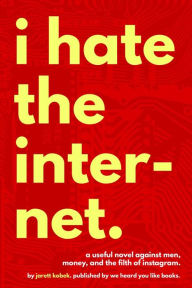

The last two years have witnessed several novels lamenting the changing cultural landscape of the Bay Area, setting their sights on the runaway capitalism of the tech industry. But few of these books have actually assimilated the language of tech into their critique. This is part of what makes Jarett Kobek’s novel I Hate the Internet (We Heard You Like Books, 288 pages) so potent.

The last two years have witnessed several novels lamenting the changing cultural landscape of the Bay Area, setting their sights on the runaway capitalism of the tech industry. But few of these books have actually assimilated the language of tech into their critique. This is part of what makes Jarett Kobek’s novel I Hate the Internet (We Heard You Like Books, 288 pages) so potent.

I Hate the Internet is ostensibly the story of Adeline, a middle-aged comic book artist living in San Francisco circa 2013. When Adeline, who purposefully affects a Trans-Atlantic accent a la Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, delivers a guest lecture at a Bay Area art school, she has no idea that her off-the-cuff remarks will be recorded and uploaded to the web by a student, generating a firestorm of Internet outrage in the process. While Adeline’s story remains an anchor throughout the novel, her dilemma is not the main focus of the book. Instead, her story serves as a springboard for Kobek to examine the state of San Francisco in the 21st century.

The narrative transitions from subject to subject at the speed of a mouse-click; a reference to Adeline’s former boyfriend working at LucasArts leads to several digressive paragraphs in which Kobek offers his own explication of the Star Wars property and its billion-dollar acquisition by the Disney corporation in 2012. This technique occurs on nearly every page, creating the impression that the reader has disappeared down a rabbit hole of URLs, following link after link on Kobek’s version of Wikipedia. It also allows Kobek to tie together several disparate threads throughout the book, while maintaining his central thesis that comic book publishers like Marvel and DC Comics—whose artists, such as Jack Kirby, saw almost none of the dizzying profits made off their intellectual properties—were the forerunners of companies like Facebook and Instagram, which earn massive revenues based on the content its millions of users produce for free.

The book’s self-stated intent is to imitate the computer network “in its obsessions with junk media” and “its irrelevant and jagged presentation of content.” The opening chapters lay out Kobek’s rejection of traditional “literary merit” as a relic of the previous century, a time when the CIA funded writer’s workshops in an attempt to utilize the American novel as a weapon in the cultural war against Soviet Russia. Questions of good taste and artistic merit are rendered meaningless in a world that, post-9/11, no longer makes sense.

But a cold discussion of I Hate the Internet’s stylistic technique undersells just how damn entertaining the book is, even as it lights a funeral pyre for the San Francisco of old. The city that was once a haven for artists and misfits is now a hotbed for companies like Twitter and various other start-ups, which Kobek wonderfully lampoons by charting the rise of “Bromato,” an app that allows tech jocks to recommend personal trainers to each other. The writer offers succinct takedowns of everything from polyamorous relationships to Burning Man and online dating, to the point that the reader often feels like a member of some future alien race sifting through the relics of the 21st century, trying to determine what led to the fall of Western civilization.

At times, I Hate the Internet is too self-referential for its own good: by the third instance of Kobek reminding the reader the book they are holding is a “bad novel,” you might be tempted to roll your eyes. There is also the sense that in critiquing a culture that makes it virtually impossible for an individual to opt out, it becomes necessary to implicate oneself as part of the very same system. Fittingly for a novel that frequently takes jabs at Objectivist writer Ayn Rand, the story ends with a John Galt-style rant, in which Kobek reminds us that “Every critique of the racist cisgender homophobic misogynistic patriarchy that you post on Tumblr just makes money for Tumblr!” There is simply no escape.

I Hate the Internet may be the first novel that arrives with its own “trigger warning,” cautioning the reader that they are about to experience “capitalism,” “despair,” and “seeing the Facebook profile of someone you knew when you were young and believed that everyone would lead rewarding lives.” Much like the latest clickbait article or Buzzfeed list floating through your Facebook feed, the book encourages its own voracious consumption, though Kobek’s writing ensures it won’t be as easily forgotten. Like a mad priest presiding over the death of our disposable culture, Kobek has delivered a fitting eulogy for the digital age.