A feature of Bruce Bond’s immense talent is his poetic economy. What he is able to articulate or suggest in a few lines requires paragraphs of exposition, a feature he shares with other truly great poets. At a recent reading, Bond briefly discussed his training as a musician, and thus a partial explanation for the elusiveness of his poetry was provided. They have a rhythm and musical sonority that propels many of them, investing their already laden words with a further force.

A feature of Bruce Bond’s immense talent is his poetic economy. What he is able to articulate or suggest in a few lines requires paragraphs of exposition, a feature he shares with other truly great poets. At a recent reading, Bond briefly discussed his training as a musician, and thus a partial explanation for the elusiveness of his poetry was provided. They have a rhythm and musical sonority that propels many of them, investing their already laden words with a further force.

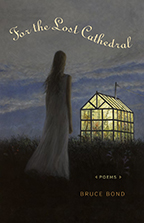

In his latest collection, For the Lost Cathedral (84 pages; LSU Press), the poems run a gamut of subject matters, from the Bone Church of Sedlic to Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project, from the seemingly small and personal, to the broad and historical. The poems are exceptional, because they raise grand metaphysical, religious, and psychological questions and expound upon possible answers, yet leave them aptly unresolved, knowing that only partial elucidations will have to suffice. The book’s first poem, “The Gate,” begins this questioning as the speaker states: “When I first learned of heaven, / it was something we lost, or was / loss simply the word we gave it.” Here Bond makes the point that much of what may seem to be a religious conceptualization of existence has an analogue in our private psyche, and thus originates there and not from some external divinity. The story of a lost paradise pervades much of Western theology, and therefore must be rooted in a distinctly human, psycho-linguistic understanding of our place within the world. We construct and perpetuate grand myths such as Eden in order to make sense of our place. “Loss” is the word given but does not necessarily have to be the reality experienced.

“Monotheism” is a meditation on the plurality of literature, as something that shares a permeable border with the forces of the natural world. The poem posits its “monotheism” as the variegated profundities which exist within a single bookshelf, and the moment of its instillation expands into a multitude of thoughts and situations, such as in the striking image that each book “waits for a reader, / the way a laurel tree waits for one to listen, / to sit beside the river and so drink / the words of the dead into those we speak.”

However, Bond’s poems do not shy away from bleakness, and he is ever attuned to the harsh realities of an imaginatively bankrupt modernity, such as in “Harvest,” where he raises the question, “Must it be the broken will / that bends our knees to speak with the unknown,” or in “Idolatry,” as the speaker sardonically ruminates on the compulsion toward consumption: “My things give me comfort, I tell my fear / in jest, in the knowledge I will lose them. / Gods come and go, they say, but things, / they are immortal.”

The poem “Proud Flesh” offers one possible alternative to this state of being, taking as its subject the human capacity for quiet suffering and endurance, casting this as a sort of triumph of autonomy, as pictured in “the man who lost his wife / to cigarettes and a plot upstate / that had no use for words” who “turned around to double-up / his own smokes and hours at work, / beating his heart to hell, to raise / some veil over the emptiness / and in its place a tower.”

If salvation exists, it seems to exist for Bond in the workings of the inner life. Our capacity for intellectual curiosity, creative speculation, skepticism, and imaginative understanding is the passage out of the drudgery; the redeeming element is the faculty of cognition. As Bond articulates it in “Air,” “dismantling the emptiness taught me / I am always there, in the music /of thought that blooms out of nowhere / and so returns.” It is not just thought, but the music of thought—the substantive something else beyond cognition—that is of central importance in these poems. This concept relates back to one expressed earlier in the collection, a verse charged with religious diction yet altered in its expression, and thus vested with an original and significant declaration of its own: “Say I am the offspring of the thought / I just had, flesh of its flesh, and so / different, in some measure culpable, free, / as anything alive.”