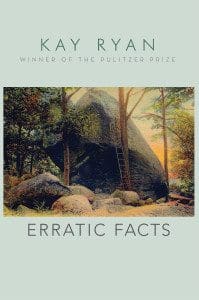

“The things we know / cannot be applied,” begins a poem in Kay Ryan’s new poetry collection, Erratic Facts (Grove Press, 64 pages), the first release since her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Best of It: New and Selected Poems. The former U.S. poet laureate returns with her signature narrow, rhyming poems to awaken and astonish us, to tilt us toward the underbelly of everyday observations.

“The things we know / cannot be applied,” begins a poem in Kay Ryan’s new poetry collection, Erratic Facts (Grove Press, 64 pages), the first release since her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Best of It: New and Selected Poems. The former U.S. poet laureate returns with her signature narrow, rhyming poems to awaken and astonish us, to tilt us toward the underbelly of everyday observations.

In the epilogue of Erratic Facts, Ryan notes:

erratic: (n) Geol. A boulder or the like

carried by glacial ice and deposited

some distance form its place of origin

This idea of displacement—a separation of boulder from its place of origin, of object from meaning—crops up again and again in her book, repeatedly overthrowing our expectations of conclusion and poetic movement. A poem titled “Shoot the Moon” ends with the shattering “bagged now and / heavy as a head,” and in “Erasure” she leaves us with the startlingly blunt statement: “this / whole area / may have been / a defactory.” The unabashed awkwardness of Ryan’s syntax also mimics the unstable nature of the erratic, as it seizes us from turn to turn: “Walls of shelves of / jars of dots equal / one dot”; “Even how / the crow / walks is / criss crosses.”

What is most important about displacement is the traveling from Point A to Point B in her poems, during which understanding is upended and the reader arrives in a world both abstract and familiar. We have the uncanny feeling we have been to Point B before, but we’re not sure how we got there. It’s like déjà vu—the halted step on a known sidewalk. In the course of this shift, Ryan creates unique spaces—like isolated, alternate worlds—of contemplation. In “Ship in a Bottle,” she opens up a universe while entrapping us behind its very walls:

It seems

impossible—

not just a

ship in a

bottle but

wind and sea.

The ship starts

to struggle—an

emergency of the

too realized we

realize. We can

get it out but

not without

spilling its world.

A hammer tap

and they’re free.

Which death

will it be,

little sailors?

In eighteen lines, she creates a Robert Browning-esque turn, transforming the reader from viewer to entangled subject. We are the actors in the bottle’s destruction as well as the little sailors spilling out. To “free” the ship means to release the reality of our world to the contained other, to reverse their definition of the word. In doing so, the word “free” reverses itself in our minds as well. At the end of the poem, we are on both sides of the glass.

These reversals, in terms of language and in the constant overturning of “the things we know,” are embedded in each of Ryan’s poems. For her, nothing is stable if we tip it the right way. In “Sock,” she writes, “Imagine an / inversion as / simple as socks: / putting your hand / into the toe of / yourself and / pulling.” As we’ve seen, this pulling inverts our understanding of reality. But it also destabilizes us emotionally, revealing a different kind of displacement at the “toe” of ourselves: sorrow. Take, for example, her poem “Eggs”:

We turn out

as tippy as

eggs. Legs

are an illusion.

We are held

as in a carton

if someone

loves us.

It’s a pity

only loss

proves this.

As we move down the page, the image of the egg morphs, invoking both the round warmth of love and the austerity of loss. How perfect of a metaphor in its eerie simplicity, how quickly we move from the familiar to the aching root of ourselves. “Eggs” is one of many poems in Erratic Facts that delivers an unsettling treatment of loss—Ryan renders it as something not curable but naturally occurring. Loss is the minor conclusion to the smooth edges of eggs; sadness is but another train of thought that follows the observation of an object.

However, Ryan also seems to say that sadness is exceptional. This emotion, pure and small and subtle, can be extracted like rare minerals from volumes of the everyday. “Bunched Cloths”—“the soft collapsing / tents, the human / moment past”—are beautiful vessels of nostalgia, and “Musical Chairs” a picture of absence. By identifying the film of loneliness veiling all that is ordinary, sorrow becomes utterly pervasive, remarkable, and most of all, real. “No / loss is token,” Ryan writes. It exists in the niches, a detectable vibration that Ryan coaxes out.

To the end, Erratic Facts is not merely an exercise in transposition but an earnest endeavor toward understanding. In the title poem (also the last poem in the book), Ryan writes that erratic facts are:

Like rocks

that just stop,

melted out

of glaciers…

As though

eggs could

really be

made backwards,

smoothed from

something

stranded

and angular.

The inversions of Erratic Facts are just a way to look at things backward so as to reach the core of each object, whether inanimate or breathing—the bright yolk of dragons or tables or socks. Ryan shares in our surprise at how each episode of understanding creeps up on us. In “On the Nature of Understanding,” she writes, “You made progress, / understanding / it would be a / lengthy process… So it’s / strange when it / attacks.” She wishes not to instruct us or claim a role in our understanding, but to emulate her own response to comprehension—to make us a part of the wonder. “Let’s think / it’s still early / in the work” she writes in the last few lines of “Erratic Facts,” “and later / the eggs / will quicken / to the center.”

One thought on “Upending What We Understand So as to Get to Wonder: ‘Erratic Facts’ by Kay Ryan”