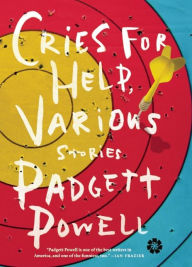

Of the various genres travestied by the entertainment industry, perhaps comedy has become the most befouled. With a few notable exceptions, inane millennial hi-jinx, “awkward” situations and encounters, and mundanely quirky characters flit across American television and computer screens with an unsurprising steadiness. In the face of this, a writer like Padgett Powell is of the greatest importance, as reminder of what comedy, specifically literary comedy, can be. Wry, strange, and with a sense of tragedy only partially concealed by the stories’ peculiar and surrealistic narratives, Cries for Help, Various (200 pages; Catapult) exhibit’s a comedy which is still in possession of its humanity.

Of the various genres travestied by the entertainment industry, perhaps comedy has become the most befouled. With a few notable exceptions, inane millennial hi-jinx, “awkward” situations and encounters, and mundanely quirky characters flit across American television and computer screens with an unsurprising steadiness. In the face of this, a writer like Padgett Powell is of the greatest importance, as reminder of what comedy, specifically literary comedy, can be. Wry, strange, and with a sense of tragedy only partially concealed by the stories’ peculiar and surrealistic narratives, Cries for Help, Various (200 pages; Catapult) exhibit’s a comedy which is still in possession of its humanity.

The highlights of the collection are the stories that have something closer to a discernable, cohesive narrative, which read less as prose poems or a mapping of a given character or narrator’s impressions. Those pieces—”Horses,” “Joplin and Dickens,” “Mrs. Fiberung,” and even “The Retarded Hermit”—have a strong, sardonic authorial voice that is largely absent from the short-short or flash fiction.

“Horses” details the situation of a nameless narrator following a group of cowboy poets, some of whom get into fights over accusations of the use of “too many feminine endings,” and who have as their absurd intention, “to take horses into Big Horn and to be ambushed by an equal or larger band of Indians and surrender them, the horses, to the Indians, and by doing so initiate a reversal of history….” The clever, peculiar strangeness of the overarching situation showcases an imaginative wealth, but the subtle details (such as the feminine end-rhyme fisticuffs) are what reveal Powell to be a comic writer of the highest order. Yet among the humor and the absurdity, there is a poignancy evoked by the inner lives of many of Powell’s characters. Having been transported to the hospital and conversing with an employee who has cleaned up the excrement of a patient who “esploded,” the narrator in “Horses” ruminates: “the way this fellow shakes his head, incredulously admiring the misfortune of the exploding patient, and the way we snicker together on the lawn is pleasing, very pleasing, in the long array of not final things during our time on Earth…I am happy…on a lawn with cold blue feet in the sun, my bowels not urgent, a friend to chat with.”

“Joplin and Dickens,” which depicts the two historical personages as middle-school classmates, fabricates a series of romantic and decidedly human interactions between the story’s unlikely pair. In the face of the young Dickens’ magniloquence, the teacher, Ms. Turner, as well as the students of the class, are forced to reflect on their existential standing: “She could not know that the children sensed their own mundane trapedness there, as she sensed hers, and that they divined in Charlie Dickens’s excesses a chance that he would by them escape and go into an orbit they themselves would be denied.” In moments like this, Powell displays a remarkable ability to articulate this sense of pervasive, private tragedy. This is also what makes the final scene of “Horses” so moving. The tranquil moment shared between the narrator and the shit-cleaning hospital employee is one of mutual understanding and mutual relief from their stations as nobodies in a farcical, blithe modernity in which hospital patients’ backed-up excrement “esplodes” and where there are gym teachers named “Dick Leech.”

After a succession of thoroughly strange and distressing events not altogether dissimilar from those depicted in the stories described above, the eponymous character of “Mrs. Fiberung” is confronted with “odd words and ideas,” which, in turn, “suggested to her the idea that she could be a radically different person from that she had been to this point in her life. Was that possible, or was it only an idea that everyone entertained once in a while and…could not quite really posses or effect?” Many of the characters within this world of variegated cries for help seem to be asking the same: to what extent can you effect autonomous change, and to what extent are you jailed in circumstances? This is by no means a novel concern in fiction, but the combination of wit and pathos employed by Powell as he constructs these surrealistic moments of relative crises are what make his take on the subject unique and eminently worthwhile. The story, aptly, leaves Mrs. Fiberung to her own quotidian issues, and ends with a discourse on the inventive brilliance of the “human buttocks.” What, in the face of absurdity both macro and microcosmic, is there left to do after all?