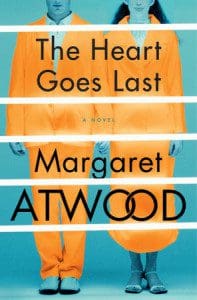

Margaret Atwood knows a thing or two million about the dystopian novel. Atwood’s latest, The Heart Goes Last (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday; 320 pages), begins familiarly: in the midst of a dire economic and social depression, a young couple chooses between freedom and chaos or comfort and constraint. As The Heart Goes Last develops, though, the form evolves from sociological study to fable. People and places turn out to not be what they seem, offering complexity but also dream-like distortions. Stan and Charmaine, the couple at the center, discover that the pressure for them to choose between good and bad, right and wrong, has little to do with embracing either notion. They begin to wonder if they are choosing anything at all. What starts as a traditional dystopian take on human mores becomes a surreal look at the breakdown of free will.

Margaret Atwood knows a thing or two million about the dystopian novel. Atwood’s latest, The Heart Goes Last (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday; 320 pages), begins familiarly: in the midst of a dire economic and social depression, a young couple chooses between freedom and chaos or comfort and constraint. As The Heart Goes Last develops, though, the form evolves from sociological study to fable. People and places turn out to not be what they seem, offering complexity but also dream-like distortions. Stan and Charmaine, the couple at the center, discover that the pressure for them to choose between good and bad, right and wrong, has little to do with embracing either notion. They begin to wonder if they are choosing anything at all. What starts as a traditional dystopian take on human mores becomes a surreal look at the breakdown of free will.

After losing their jobs and homes in a massive fiscal downturn, Stan and Charmaine are living in their car, fleeing from roaming vandals and looters, and surviving off of Charmaine’s meager tips at a sleazy dive and off the spongy fried chicken wings she gets from the shop next door. Theirs is a contemporary situation taken to a logical extreme. When Charmaine sees an advertisement for a program offering families and individuals a return to the comfortable and quaint middle class existence they had before, she can’t resist. “Remember what your life used to be like?” the man in the ad asks. Neither she nor Stan fully realize the repercussions of their signing up for the Consilience/Positron twin cities project.

The town of Consilience seems too good to be true, because, like a proper dystopia, it is. Participants in the project agree to spend one month living as “civilians” with full time employment, access to health care, and well-kept suburban style homes. They are even given adorable electric scooters to zip around town, saving on emissions and transportation costs. On the alternate months, they serve as prisoners in the local Positron Prison. It’s a system motivated by ideas not far removed from our current prison-industrial complex: “And if every citizen were either a guard or a prisoner, the result would be full employment: half would be prisoners, the other half would be engaged in the business of tending the prisoners in some way or other,” Ed, the founder of Consilience, explains. It’s all very practical. Despite the sacrifice of certain personal liberties, the possibility of future comforts tantalizes the desperate participants in a way that mimics ideologies of consumerism: good debt leads to better credit scores.

Life in Consilience starts out like the Doris Day records played on repeat there, meant to evoke nostalgia and banish bad feelings (though The Heart doesn’t address how this might evoke opposite feelings in participants who do not have the best of historical associations with 1950s U.S.). Stan and Charmaine have all the security they missed so much while living in a car. And while life during the months in the Positron Prison does become a little tedious, boring, and even constricting, Stan views this as he views his relationship with Charmaine. “Transparency, certainty, fidelity: his various humiliations had taught him to value those.” This is what they bargained for; they accept the costs. However, with time, Stan and Charmaine slip further into a maze that distorts everything they thought they understood.

The second half of the novel takes us down a rabbit hole, transforming the story from dystopia to surreal thriller and farce. Charmaine leads the dizzying spiral. As her indiscretions come to light—adulteress, liar, manipulator, and far worse—so do those of the town of Consilience and its slick as an eel leader, Ed. Charmaine and Stan become pawns in an elaborate plot to bring down Consilience for reasons that may not be wholly good, but like everything else, are skewed beyond recognition. For not only are the objects of the characters’ decisions illusions, but so is the very act of choosing, imbued as it is with crooked self-interests and problematic histories.

At one point, a woman from Consilience presents Charmaine with an offer. “You can choose,” she says, “to hear it or not. If you hear it, you’ll be more free but less secure. If you don’t hear it, you’ll be more secure, but less free.” The Heart Goes Last supposes what it would mean to be free of the stress of having to make decisions or exercise free will. What lays beyond that premise are continuing labyrinths twisting across a dark landscape.