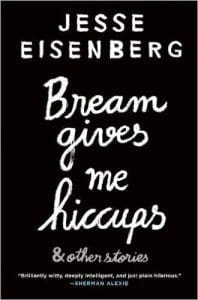

If Jesse Eisenberg’s first fiction collection were made up of simple extended bits, in which Eisenberg takes an initial premise and wittily wrings it for every drop of comedic juice possible, the book would still be an entertaining read. What makes Bream Gives Me Hiccups (Grove; 256 pages) more than that, however, is the dissection of social anxiety underlying each piece. Through a myriad of perspectives—from a precocious, broken-homed nine-year-old boy and an obnoxious college freshman with self-projection issues to Carmelo Anthony after an irritating run-in with a fan—Eisenberg relates a collective understanding of how difficult it is to both like others and also feel liked.

If Jesse Eisenberg’s first fiction collection were made up of simple extended bits, in which Eisenberg takes an initial premise and wittily wrings it for every drop of comedic juice possible, the book would still be an entertaining read. What makes Bream Gives Me Hiccups (Grove; 256 pages) more than that, however, is the dissection of social anxiety underlying each piece. Through a myriad of perspectives—from a precocious, broken-homed nine-year-old boy and an obnoxious college freshman with self-projection issues to Carmelo Anthony after an irritating run-in with a fan—Eisenberg relates a collective understanding of how difficult it is to both like others and also feel liked.

At first it’s hard to imagine any continuity in a collection that features the Bosnian genocide, Alexander Graham Bell, and a guy at a bar tripping on manufactured hallucinogens. But Eisenberg, through intimate points of view, a commitment to each comic premise, and a nerdy but unpretentious deployment of knowledge, links these seemingly unrelated stories. He shows that at base everyone has that Charlie Brown-like combination of hope and disappointment: cynical enough to know the football is going to be swiped away at the last moment, but hopeful (or possibly deluded) enough to try again, anyway.

In the section titled “Dating,” there are four takes on the set-up “A [blank] tries to pick up a [blank] in a bar,” and in each Eisenberg milks the joke ad absurdum. My personal favorite, “A lifelong teetotaler embarrassed by his own sobriety, tries to pick up a woman at a bar,” features a speaker desperate to fit in to bar culture, and terrified by the prospect. His or her far too eager insistence on loving alcohol is hilariously awkward. The speaker notes how many different types of alcohol there are, “which is so cool,” provides histories of alcoholic etymology, and buddies up to a barkeep who clearly has no idea who the speaker is: “He’ll hook me up. He’s a friend. On account of me being here so frequently and drinking alcohol.” By the end, the word “alcohol” alone becomes a joke.

Eisenberg’s characterizations are light and dexterous, and almost neurotically close. Even when not using the first person point of view, the reader is given enough unpolished quirk to not just think we know the character, but that we are watching our very social anxieties manifesting in the stories. In “An email exchange with my first girlfriend…” the unidentified high school Romeo messages his first love, Amy, “I really like too… / I mean I really like YOU too! / Whoops…” and the typo is so awkward and familiar that it hurts.

Harper Jablonski, fictional author of “Letters from a Frustrated Freshman,” is arguably the most unlikable character in the book: vapid, self-centered, and judgmental to boot. The proximity with which Eisenberg depicts her produces humor, yes, but also sympathy for the student. After going out to dinner with her roommate (whom Harper has nicknamed “Slutnick”) and her roommate’s parents, Harper realizes she just experienced a family who enjoys each other and looks out for each others’ interests and, to her surprise, she likes it. The sentimental moment, though, is cut short when Slutnick walks back in the room after a shower and Harper writes, “I thought it was embarrassing that I had a fat roommate and I was worried people would think I was fat, just by association.” Eisenberg tempers his character’s emotional growth with these more unbecoming thoughts: becoming a better person is often an unglamorous battle with the less attractive versions of ourselves.

The learning in the book is written as vividly as the characters. Eisenberg’s clear fascination with the “stuff” of the world—history, sports, artifacts, figures, Yelp reviews—instigate as much storytelling and wit as the characters and their crises or foibles. “My Prescription Information Pamphlets As Written By My Father” is as hilarious an interpretation of a lovingly manipulative father as it is an exacting look at modern well-being. The father writes tongue-in-cheek recommendations for four drugs his son has been prescribed: Ativan, Adderall, Zoloft, and Haldol, all of which are incredibly common, but as the bit implies, pretty insidious. Everything the father writes earns a laugh (“If you want me to keep paying for your COBRA so you can pay this shrink, you need to get a job”), but also a cringe. He harbors a deeper knowledge of what these drugs do to someone who perhaps does not need them but just wants to feel good, even if it’s the most artificial sort of good feeling. Regarding Adderall, the dad notes, “In case of overdose: Taking any amount of this medication is an overdose.”

Bream Makes Me Hiccup attests to Eisenberg’s understanding of our cultural moment in which art and pop are still meeting, and still clashing. It is not the most uplifting book, and endearingly so; rather than sacrifice reality for sentiment (or vice versa), Eisenberg vacillates between the two. The results are characters and stories that at first make you laugh, then think, then sigh.