During the Renaissance, it may have been the Italians who mastered the painted canvas, but it was the Northern Europeans who mastered the print. Perhaps the best artist to come out of that period, Albrecht Dürer (1472-1528) sought to prove he could do with woodblocks and copper plates what any Italian painter boasted with his paintbrush. Perspective, proportion, and balance, Dürer achieved it all.

In Reformations: Dürer and the New Age of Print, an exhibit running at the Thacher Gallery at the University of San Francisco till February 22, prints by the legendary print-maker are showcased along with some of the first books to be made using moveable type and printing presses. Collectively, the pieces consider the impact of this Renaissance technology as it transformed social, cultural, and artistic movements. While slow, these transitions are striking; one enters the dimly-lit space to examine cases of manuscripts—hand-written works of art that alone warrant a visit to this free show—and continues along to see some of the earliest surviving printed books, mainly religious texts beautifully bound and hand-colored. These texts, though old, reveal not only the developing technology of bookmaking but also the technology of reading. Bookmakers used visual tricks to draw the reader’s eye to important parts of the text. Red marks often highlight the beginning of each sentence, making the mass of letters on the page more digestible.

For those further intrigued by the evolution of books, the exhibit continues upstairs at the Donohue Rare Book Room (open Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.). Featuring an impressive collection of some of the first printed humanist books—including works by Virgil, Ovid, and Dante, along with the first printed edition of Vitruvius (with woodcut printed illustrations accompanying the text) and an intriguing pocket-sized, hand-colored botanical book chronicling the characteristics and benefits of various herbs —the display captures the way printed books were used to disseminate different forms of knowledge across Europe.

But it is Dürer who rightfully holds center stage here. Born in Nuremberg, a city known at the time for its guilds and artisan culture, he grew up among goldsmiths-turned-printers. One of these was his godfather, Anton Koberger, who founded Nuremberg’s first printing press. Studying under another artist and working for his godfather, Dürer became an expert in the field.

His talent is unfathomable. The curators wisely supply magnifying glasses so visitors can examine the expert detail Dürer meticulously incorporated into his works, despite the difficulty of overworking wood (it splinters, cracks, expands, etc.). Dynamic scenes fill the foreground, while cityscapes and landscapes (which the Northerners were known for) flank the background. Keen observers will look past the bold lines depicting the scenes from the prints from “Small Woodcut Passion” (1509-1511) and “Life of the Virgin” (1500-1511) to notice miniscule goats roaming the hillsides, birds migrating home in the distant sky, and cracks forming at the foundation of a building. In a print aptly called “The Ascension” (1511), an ascending Christ leaves footprints behind him on the hill.

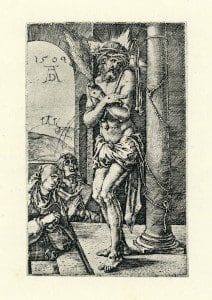

But perhaps most striking of all are Dürer’s engravings from the intaglio series “Engraved Passion” (1508-1513). For those unfamiliar with the art form, intaglio, or “engravings,” differ from relief prints (like woodblocks, for example) in which one carves away the empty space, leaving behind the image to be inked and printed. In intaglio, one etches into a copper plate. The sunken line left behind is then filled with the ink and becomes the positive image on the paper, creating positive space from the negative. The plate allows for more precision but is much more difficult to carve. Unlike his woodcuts, which were made for the general public, Dürer’s engravings exhibited his finest skills and were aimed at collectors. Before Dürer it was common to view printmaking as simply another element of book manufacturing rather than a form of fine and intellectual art. Dürer proved this notion false.

The faces are worth mentioning, too. As Professor Kate Lusheck, one of the show’s curators, pointed out to me, Dürer depicts a complicated and subtle narrative with his characters’ array of diverse and striking facial expressions. The scenes are dynamic. In the woodcut “Christ Taken Captive” (1511), we see Christ’s dramatic expression of repulsion as Judas gives him a treacherous kiss, war unfolding chaotically about them.

Lusheck and John Hawks, Head of Special Collections, came up with the general idea for this exhibit. They wanted to give students in USF’s master’s in Museum Studies program the experience of putting together a show, while putting the university’s amazing collection of rare books on display for the public. The result is a remarkable experience.