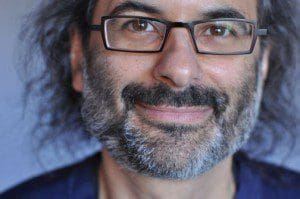

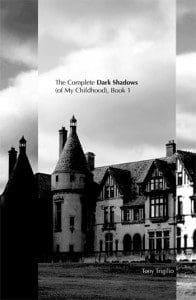

The Complete Dark Shadows (of My Childhood): Book 1 (BlazeVOX; 104 pages) is a batty new book-length poem from Chicago poet Tony Trigilio that takes as its inspiration the ’60s Gothic soap opera, Dark Shadows. Since he watched the series as a child with his mother, Trigilio has been haunted by the series’ vampiric hero, Barnabas Collins, whose compulsive bloodlust fostered a host of neuroses in the young poet. In an effort to face his demons, compose his memoirs, and keep alive the memory of his mother—all the while combining elements of kitsch, ekphrasis, and new formalism—Trigilio writes one sentence for each of the 1,225 episodes of Dark Shadows, which he then enjambs into series of couplets. Book 1, comprising episodes 210 through 392, is the first installation of the project. By turns comic and heartrending, lyric and absurd, The Complete Dark Shadows (of My Childhood) collages elements from dreams, memories, and pop-culture into a strangely compelling portrait of the little boy who turned into Tony Trigilio. We interviewed Trigilio about his new book via email.

ZYZZYVA: I want to start by asking how this book came about. You mention that David Trinidad sent you the link to the boxed set on Amazon, but I wonder if you had conceived of the project before then—if systematically revisiting Dark Shadows was a task you knew would be necessary for creative and psychological growth?

Tony Trigilio: David’s soap opera epic, Peyton Place: A Haiku Soap Opera, is a direct inspiration for my book. He’s a very close friend, and we regularly exchange and critique each other’s poems. As we talked about his Peyton Place haiku—he wrote one haiku for every episode of Peyton Place—we occasionally found ourselves on tangents about the Dark Shadows fixations that haunted me as a child. He encouraged me to write about them, and the idea for the poem took off from there. I felt I couldn’t just respond to individual episodes or scenes or images. Instead, I had to write about the show in its totality. The only way to do this was to watch every minute of every episode—one sentence per episode, trusting the ekphrastic mode to guide the poems where they needed to go autobiographically.

Sounds great, but here’s where I nearly went off the rails: I thought Dark Shadows only consisted of 300-400 episodes when I started the project, and I didn’t realize until I was 38 episodes into the project that the show actually lasted for 1,225 episodes. Watching over a thousand episodes of a soap opera seemed too outrageous to even imagine. So I decided to try to imagine it. After all, I had only written 38 sentences at this point in the project, which made me feel like the poem could absorb any kind of radical change in my method. I really hadn’t become attached to anything structural in the poem yet, except working from sentence-based phrasing and breaking the lines into couplets, and then concluding each segment of the poem with a final, one-line stanza. The poem became a kind of impossible object once I realized I had committed to 1,225 sentences. And I loved how this change in plans introduced a new tension in my writing process, forcing a collision between my fixations on the minute particulars of language-making and the patience required for writing as an act of radical endurance.

I actually had tried to write about Dark Shadows a few times in the past, but not in any kind of procedural or systematic way. Barnabas Collins appeared as an allegorical figure in a couple poems that I eventually cut from Historic Diary. I haven’t done anything with these poems since then, but I’ve let them rattle around in my unconscious and I have a feeling they could show up in a future volume of The Complete Dark Shadows (of My Childhood). Earlier, in the mid-1990s, I started what I thought would be a long essay on my Barnabas Collins childhood nightmares. I didn’t get very far before abandoning it, but I did find the essay recently. It was printed on recyclable paper that is now brittle and yellowing. I’m including an excerpt from this essay at the beginning of Book 2 of this poem. (I’m happily working on Book 2 right now—finally out of the interminable 1795 plot-line and now filtering Dark Shadows, and my life, through the violence of 1968.)

I think I’ve always known that revisiting Dark Shadows was important to my creative and psychological growth. The Barnabas Collins nightmares in my childhood were incessant—he was almost like a family member for me. Dark Shadows was where I became first acquainted with the rudimentary activities of my psyche. I was way too young to know anything about the unconscious mind, but at the same time, the constant Barnabas nightmares taught me that the events of the day roiled somewhere in the back of my mind and got dramatized at night when I slept with my shoulders hunched to ward off vampires.

Z: For me, a lot of the most uncanny moments of the book were points when I wasn’t sure whether you were referring to a person in your life or a character or actor from Dark Shadows. This was compounded by the facts that the same actor would play several different roles in the soap, and that your mother shared her name with one of the leads: Maggie. (All the more uncanny since it’s my name, too.) Did you find yourself noticing resonances between the real and the fictional? How did you see narratives from your own life reflected in the show, particularly in the character of Little David?

TT: My hope is that the leaps between the real and the fictional in the book will blur the boundaries between my life and the lives of the characters in Dark Shadows, and I’m glad to hear how much this comes out in the poem. I watched the show at such a young age that I personalized everything in it. The bite marks on Maggie’s neck were my own. Victoria Winters’s exposed neck was my own. And when I got to the plotline where Barnabas stalks Little David, I could see, of course, where I got hooked as a child. Here’s a little boy who, like me, suffers from insomnia because a vampire wants to destroy him—no wonder I was convinced Barnabas was watching me outside my bedroom window every night! Little David is also a psychic child, and as a boy I identified with his attraction to the occult. His mother was a Phoenix; my mother was a mere mortal, but her own mother practiced a kind of voodoo Catholicism as a girl in Italy (and this, along with my mother’s fascination with the Salem witch trials, inaugurated my lifelong interest in psychic phenomena). Plus, Little David could contact a ghost girl with his crystal ball. I would’ve given anything as a child to possess a supernatural crystal ball!

Z: At what point did you understand that Dark Shadows was camp? Was there a point as a child when the lightbulb went on that this, to quote Sontag, is “good because it’s awful?” Did noticing the bloopers, melodramatic production, and low-budget effects make you any less scared of or invested in the series?

TT: This is such a great question—one of my most exciting discoveries, watching the show now as an adult, is that it’s so kitschy. But it felt real to me when I first watched it as a child. I think I was too scared of it back then to notice the bloopers. (Also, when I was a boy, we had a small black-and-white TV, which probably made some of the production values seem less contrived. You can’t see the stagehands mistakenly caught on videotape, for instance, on a tiny TV.) I actually believed at one point that Barnabas Collins lived inside the walls of my house. The exposed-brick wallpaper pattern in our living room, bought from K-Mart, was definitely kitsch—but I was too frightened to really pay attention to the brick pattern because a vampire lived in the walls.

Z: The Complete Dark Shadows (of my Childhood) is chock-full of literary and pop-cultural allusions: Poe, Johnny Depp, Joy Division, John Cage, Mates of State, and Kafka are just a few of the names mentioned. I learned from Wikipedia that Dark Shadows itself is rich in literary references; a lot of the episodes are inspired by stories, poems, and myths. What is the connection, in your mind, between the soap opera and literature as artistic media?

TT: I watched so many soap operas as a child with my mother, not just Dark Shadows, and I think soaps are where I first learned to think of literature in serialized terms. By “serialized,” I don’t just mean the linearity of serial narrative, but also the associative, non-linear movements of what we’d call a serial poem. I’m working on Book 2, for instance, and I just finished a 92-episode narrative arc that took place in the year 1795. The 1795 plotline didn’t feature a lot of distinctive events. Instead, it stretched and elongated a few plot twists as far as they could possibly go—while occasionally introducing short, four-or-five-episode tangents that absolutely spun the show’s narrative out of control. Soap opera storylines are interminable—and this is part of what I love about them, because they offer so much space for the linear and non-linear to clash.

Z: Often, you applied additional formal constraints to your couplets, shaping them into ghazals and sonnets, end-rhyming them and making use of anaphora. How did you choose when further formal constraints were called for, and did you find that these constraints were more generative or restrictive?

Z: Often, you applied additional formal constraints to your couplets, shaping them into ghazals and sonnets, end-rhyming them and making use of anaphora. How did you choose when further formal constraints were called for, and did you find that these constraints were more generative or restrictive?

TT: I try to let these choices suggest themselves organically, and they usually present themselves during moments when I feel like I need to add more dynamic range to the poem’s voices. The formal constraints are almost magically generative and restrictive. When I started the ghazals, for instance, I worried at first that I was adding too many tentacles to the poem—autobiography, ekphrasis, couplets, and then, yow, the ghazal. But of course the restrictiveness of the form radically changed the direction of what I could say and, in turn, intensified what I was seeing.

I also sometimes choose a formal constraint to highlight, celebrate, or commemorate a significant episode or plotline. Occasionally, I also choose a form to mark a significant event from real life, such as when I acknowledged the death of Jonathan Frid (the actor who played Barnabas) with a series of rhyming couplets that made this segment of the poem feel, I hope, more self-consciously elegiac. In a segment I recently finished for Book 2, I use an abecedarian to dramatize the moment Barnabas is actually turned into a vampire. This forced a compactness in the language and the lines that might not have occurred to me otherwise during this huge moment in the show.

Z: There’s a moment on Page 41 when the speaker breaks from his account of the episode to say, “I worry I’m not writing a long poem but building an impossible object like Ken Applegate’s Matchstick Space Shuttle, which I saw this weekend at the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Museum’s Odditorium in San Francisco… .” That kind of self-referentiality can be really annoying in poetry, I think, but it works so well here—it reads as boyish and paranoid and irreverent. Because its characters and settings were already so numerous, did you find this poem lent itself to reflexivity and digression? Did you find it easier to jump associatively from place to place?

TT: Thanks for your comments on the self-referential and digressive moments. I worried that those moments could be annoying or gimmicky. But, as you suggest, the show’s multiple characters and settings almost seemed to require self-referential excursions in the poem. When Barnabas, for instance, ages four decades in one episode, becoming stooped and elderly, it invited me to consider—with lots of anxiety—that I might still not be finished with the poem and its 1,225 episodes until I, too, am frail and aged. And that’s only if I get to live to be frail and aged. The endurance required to actually finish this poem makes me think a lot about my own death—the frightening reality of my future death, the possibility that I might not outlive my own poem—and this has given me permission for self-referential digressions in the poem that recognize the presence of death.

I never could have anticipated that the writing of this poem would make me reflect so much on my own mortality. I’m grateful for this. (All the same, I’m only 47, and I hope to live a long, healthy life.) I don’t know why the self-referential tangents about dying should have surprised me. I mean, after all, I am writing about coffins, mausoleums, ghosts, and all manner of undead. Also, I began the poem rattled by a series of deaths I’d recently experienced. In the five years leading up to the beginning of this poem, my father, my brother, my ex-mother-law, and my dear cat died, and I went through a divorce, another kind of death. No surprise, I guess, that this project really started to take off as I emerged from the fog of these losses.

I’m glad you also experienced the self-referential moments as irreverent. The irreverence of this book is, I think, partly an effect of surrendering to all kinds of autobiographical realities—exuberant moments, but at times also snarky, anxious, or paranoid states, too. When all the volumes are finished, the poem will be big enough for all states of consciousness, I hope. All my nerves are welcome.

Z: So what’s the deal with pop culture and vampires? Is there something transpersonal and/or deeply psychological about their appeal, do you think? Put differently, what does our cultural obsession with these bloodsuckers tell us about ourselves?

TT: I think one of the reasons I’m writing the poem is to answer this question for myself. This question has been bothering me for as long as I’ve been obsessed with vampires—before I even came into language. Maybe it’s that they’re the perfect fusion of our sex and death drives. The slick sex appeal of vampires is obvious, but really crucial, I think. I remember learning what a hickey was in junior high and realizing—yow!—there’s a fine line between a hickey and a vampire bite. (By the way, this is the first time I remembered the hickey-vampire moment, so don’t be surprised if it turns up in a future volume of the poem. I’ll be sure to cite our interview!) To go a bit further, I think the vampire represents the fear and allure of hypersexuality for us: even though the vampire myth is a malleable narrative, vampires usually are portrayed as insatiable, and I think that we see with some anxiety and excitement our own insatiability in them—a fear of, and attraction to, our wildest animal libido. Werewolves, for instance, don’t do the same thing, I think, because they’re so obviously associated with canines. Vampires, on the other hand, are us, fully human as much as they are dead. They’re both dead and alive at the same time. They’ve seen “the other side,” and they’ve come back to walk among us. They died and were placed in satin-lined caskets . . . and then walked back out, alive. I can’t imagine not being obsessed with what they know and what they’ve experienced.

Z: Bonus question, to satisfy my own curiosity: did you ever get into Twin Peaks? I feel like you would really like it (except maybe not, because it self-consciously does a lot of the anachronistic campy stuff Dark Shadows does in earnest.) Anyway, Lynch fan or no?

TT: Absolutely, yes. I keep a photo of him taped to my computer at work so that I can remember that the strange and surreal can exist even underneath the most predictable moments of the workaday world. As I said recently in an email conversation with my friend, the poet Angela Genusa (another Lynch fan), I consider David Lynch the patron saint of everything creative in my life.