In a 1917 appraisal of Siegfried Sassoon’s first collection of war poems, The Huntsman, Virginia Woolf lauded the poet for revealing all those things about the present war that are “sordid and horrible.” To Woolf, Sassoon’s poetry surpassed mere reportage to offer civic value by underlining the tacit complicity of a silent British home front. Sassoon is able to produce in his poems, Woolf writes, “an uneasy desire to leave our place in the audience.”

In a 1917 appraisal of Siegfried Sassoon’s first collection of war poems, The Huntsman, Virginia Woolf lauded the poet for revealing all those things about the present war that are “sordid and horrible.” To Woolf, Sassoon’s poetry surpassed mere reportage to offer civic value by underlining the tacit complicity of a silent British home front. Sassoon is able to produce in his poems, Woolf writes, “an uneasy desire to leave our place in the audience.”

Pity, it would seem, is what Woolf admires in Sassoon’s war realism; pity is the impetus of this “uneasy desire” to leave the audience. Wilfred Owen, who stopped imitating Keats for working in the shadow of Sassoon’s realism, famously expressed the primacy of this quality in a preface he drafted to his poems (before dying in battle): “Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

But poets Ivor Gurney, David Jones, and Isaac Rosenberg cultivated a poetics of individual experience around the Great War, as well, one in which poetry is not a melodramatic witness meant to upend glorified depictions of war (such as with the work of Sassoon and Owen) but a site of imagination, trying to carve a space for humanity in reaction to depraved and destructive forces. In Gurney’s words from a 1916 letter to Marion Scott, the artist is a point of crystallization wherein later generations can learn “what thoughts haunted the minds of men who watched the darkness grimly in desolate places.”

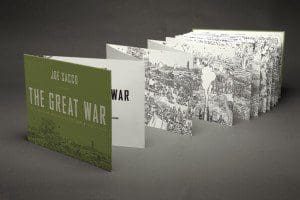

Joe Sacco’s new book, The Great War (W. W. Norton & Company)—a twenty-four-foot, foldout panorama depicting preparations for and the carnage of the first day of the Battle of the Somme—is the historical analogue of Gurney’s artist. Rather than showing what haunts the mind of infantrymen gripped by vacillations between extreme boredom and violence, Sacco trenchantly depicts the thoughts that haunt the minds of contemporary men and women as they look back at the atrocities of World War I. Sacco has compressed archival footage from, among other sources, London’s Imperial War Museum into pungent arabesques. In a marching procession, soldiers smile and wave at cameras while others maintain stern countenance, seemingly in anxiety. In another panel, at 7:30 a.m. on 1 July 1916, soldiers clamber up trench ladders, wading out into no-man’s-land. Disaster is seen in the periphery and the eye scans to the right to see swirls of artillery debris mix with clouds of white chalk sent up from machine gun fire. Tiny body parts are scattered across the page or are carried back on stretchers to be stacked in ambulances. There are faces in frightened apprehension, in contorted pain and in despairing bafflement staring at the dead being buried. All of this happens without a single dialogue balloon or exposition-carrying box. The Great War is a book of witness without commentary by an author who, in all but a matter of speaking, wasn’t there.

Although this absence marks a seeming departure from Sacco’s globe-trotting journalistic endeavors in which he draws a caricature of himself into most panels—works including “Footnotes in Gaza,” his 2009 account of the 1956 massacre killings of over 300 Palestinians in Khan Younis and in Rafah by Israeli forces; “Safe Area Goražde,” his 2000 account of the Serbian siege of the Bosnia city of Goražde; and “The Fixer: A Story from Sarajevo,” a chronicle of a former paramilitary who becomes a “fixer,” selling stories to war correspondents in Sarajevo—the differences are merely formal and topical. While conflict remains a concurrent theme in each of Sacco’s works, their most pressing concern is historical memory. Exemplarily, in the foreword to “Footnotes in Gaza,” Sacco describes his frustration after an editor at Harper’s magazine decided to excise an account of the Khan Younis massacre:

“I found [the excision] galling. This episode—seemingly the greatest massacre of Palestinians on Palestinian soil, if the U.N. figures of 275 dead are to be believed—hardly deserved to be thrown back on the pile of obscurity. But there it lay, like innumerable historical tragedies over the ages that barely rate footnote status in the broad sweep of history—even though, as El Rantisi alluded, they often contain the seeds of the grief that shape present-day events.”

The asymmetrical relationship between objective historical record and the collective or personal historical conscious is central to most of Sacco’s poignant work. His narrative arcs forego facile linear progression in favor of inextricable webs of personal narrative—narratives that often do not meet the criteria of historians—and factual record, moving fluidly between degrees of past and the present. The result is a story in which clock-time gives way to the reader concurrently experiencing the past and present.

The Great War offers a variation on a similar theme, as Sacco hints at in the Author’s Note:

“The First World War has loomed large in my psyche since my schoolboy days in Australia when every April 25 we commemorated the anniversary of the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli. I was cognizant then, that a war dubbed The War to End All Wars must have thrown up such horrors that the survivors believed it was the last word on the matter. My fascination with the war in which armies clubbed each other for year after year over small bits of ground has never abated. I own shelves of books about the subject.”

To explore how the loss of this war has informed his contemporary worldview, Sacco has created an immersive memory of intractable materiality, an echo chamber in which we inhabit a cultural memory. To view the panels completely unfurled, one must spread the book out upon a long stretch of flooring, and crawl on hands and knees, fittingly in pain at points. The psychic pain is different from Owen’s pang of pity. It is a pain formed in the apprehension of how difficult remembrance and commemoration are against the ease with which everything can slip into oblivion. In most homes, there will not be a vantage point high enough to see both the panel of General Douglas Haig walking outside Château de Beaurepaire and the panel of a baffled solider staring across fresh graves, holding in his hand what one can only assume is a book tabulating the names of the dead (almost 20,000 British soldiers were killed, and another 40,000 were wounded, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme); and if a home did afford such a view, one would certainly lose any sense of history as a place of participation of equal loss, where the viewer can constantly make discoveries within a memory.

Three years after being honorably discharged on account of shell shock, Ivor Gurney was admitted to a mental asylum where he died fifteen years later. Gurney’s tragedy is similar to that of an account of a solider in Martin Middlebrook’s First Day on the Somme:

“Later that year [a soldier who partook in the recovery and identification of corpses] was in Nottingham, on leave, and happened to meet the mother of one of the men he had identified. She had always refused to believe that her son was dead, even when notified that his body had been found. [The solider] was forced to tell her that he had personally recovered and identified [her son’s] body. She died within a month.”

For Gurney, the men who served, and family members, World War I did not have a fixed end. Across time to the contemporary, the Great War remains a baffling force that requires belated witness.