The recent award of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Alice Munro was one of those cultural events which seemed uniquely well-deserved, if just because of the Canadian author’s modest attention to the little disturbances of men—and women— that give life meaning and shape. It may mean—I hope it means—a rebirth of interest in the short story, a form that while notoriously hard to “brand” in the publishing world, is uniquely qualified to communicate such particularities.

The recent award of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Alice Munro was one of those cultural events which seemed uniquely well-deserved, if just because of the Canadian author’s modest attention to the little disturbances of men—and women— that give life meaning and shape. It may mean—I hope it means—a rebirth of interest in the short story, a form that while notoriously hard to “brand” in the publishing world, is uniquely qualified to communicate such particularities.

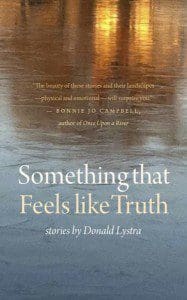

Donald Lystra explores this territory with tact and precision in his new collection, Something That Feels Like Truth (Switchgrass Books/Northern Illinois University Press). A Michigan native and retired engineer who came to writing late in life (his first novel was Season of Water and Ice), Lystra’s quiet stories recall the rhythms of Raymond Carver’s and the unhappy angst of (early) Beattie, although Hemingway’s Nick Adams tales are the more obvious antecedents.

The first story, “Geese,’’ sets the collection’s tone. It is told through the point of view of Glenn, who is accompanying his wife on a visit to her brother, Carl, just before he goes in for cancer surgery. But first, Carl wants to put down his sick dog—shoot him, not take him to the vet—an irrational request on an already stress-filled day.

“Eileen and Carl were closer than most brothers and sisters, and that was something I had learned to live with,” Lystra writes. “When they were just kids their mother had run off to Oregon with a man who raised hunting dogs, and she had not come back, so Eileen—who was nine years older than Carl—had become a sort of surrogate mother…More than once I’ve awakened in the middle of the night and found her downstairs at the kitchen table, the telephone in her ear, talking to Carl in that sweet, measured voice of hers, that sweet, middle-of-the-night voice that held the promise that, come morning, everything would be all right.”

Everything isn’t all right. Over his wife’s objections, to avoid an escalating brother-sister argument, Glenn volunteers to kill the dog himself, and buries him back of the house. When he calls the hospital to check on Glenn’s condition, he’s still in shock:

“I still had that feeling from being back in the woods and my heart was pounding like crazy. I moved over to the picture window and looked out onto the lake. The Canada geese were still down there, only now the north wind was riffling the water and a black skin of ice was starting to form. The geese paddled and flapped their wings, trying to keep some open water around them. At Eileen’s end, I heard a door slam.’’

It’s all absorbing and understated. In some ways, Lystra’s work is reminiscent of his fellow Michiganite Elmore Leonard (absent the mobsters and melee) in its admirable Midwestern reserve.

Other pieces in this worthy debut worth mentioning: “Reckless,’’ an account of a hunting trip gone bad that explores class differences between the youthful narrator’s father, a GM worker who’d crossed the line into “management,’’ and his one-time pal, who deliberately trespasses in an increasingly clear effort to rattle his upwardly mobile friend’s cage; “Treasure Hunt,’’ the tale of a kid whose cello-playing prodigy of a brother inexplicably turns to the world of crime; and “Rain Check,’’ in which a recently widowed father takes his daughter to San Francisco, picks up a drunken woman at a bar, then thinks better of it.

But summaries don’t do them justice. It’s Lystra’s lucid voice that stops you cold.

“There were many separate parts to grief—Eddie knew that now—but the hardest parts were certainly behind them,’’ he writes, in “Rain Check.” “They were past the numb, sleepwalk-feeling part and also the panicky, waking-in-the-night part. They were past the part where he and Angela traded small brave smiles whenever they happened to connect and they were past the part where Eddie would suddenly realize, on going to bed, that they had forgotten to have dinner… And they were past the part where you fight down sudden tears in the midst of business meetings, backyard barbecues, favorite television shows, and also the part where you brace up against a seizing anger when friends make sympathetic small talk, and also the part where you clinch your fists against sudden and destructive rages. They were past all those parts.”

Collections like this are a welcome antidote to the “loose baggy monsters’’ of the contemporary novel (are you listening, Jonathan Franzen) or the hipster artifacts of the moment. The Big Two-Hearted River is still running, and you can’t step in it twice.