After a big-top production of Othello performed in a dilapidated, almost apocalyptic Chicago, Bruno Korsawski poses a strange question to his uneasy companion: “I wonder which one of us is more scared of the other.” Bruno’s inquiry reflects a mood that runs through much of The Complete Stories of James Purdy (Liveright/Norton; 724 pages)— that of universal paranoia, distrust, and fear, coupled with an intense sense of personal interdependence.

After a big-top production of Othello performed in a dilapidated, almost apocalyptic Chicago, Bruno Korsawski poses a strange question to his uneasy companion: “I wonder which one of us is more scared of the other.” Bruno’s inquiry reflects a mood that runs through much of The Complete Stories of James Purdy (Liveright/Norton; 724 pages)— that of universal paranoia, distrust, and fear, coupled with an intense sense of personal interdependence.

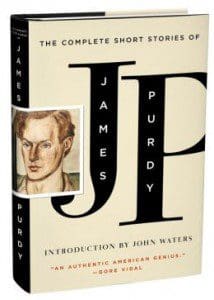

Purdy (1914-2009) was admired by a wide range of authors and readers for his transgressive and often hilarious fictions, and produced an immense body of work that includes plays, poetry, novels, and short stories. Collected in their totality for the first time, Purdy’s Complete Stories contains fiction spanning his entire career, from “A Chance to Say No,” written in 1935, to 2003’s “Adeline” (both of which were previously unpublished). Filmmaker John Waters introduces the volume by way of a loving, appropriately uncomfortable essay in which he refers to Purdy as “a drug one can never get enough of.” Purdy’s talents are apparent throughout this mammoth story collection, which feature a panoply of unusual outcasts moving through equally off-kilter environments, from a would-be heirloom collector trapped in a gothic mansion to a “retired” cannibal (“not through age, but by law and regulation”) named Mud Toe who cavorts through the cosmopolitan labyrinth of Manhattan.

Fenton Riddleway, to whom Bruno’s pertinent question is posed, is at the center of “63: Dream Palace,” one of the collection’s longest stories. (Initially rejected by publishers, the story was first released as a novella by a private imprint in 1956.) Fenton is a West Virginia native transplanted into a nightmarish vision of Chicago, where he lives in a rundown rooming house with his ill younger brother, Claire. Purdy frames the narrative as a story recollected by Parkhearst Cratty—an aspiring but impotent writer—to his friend, “the greatwoman” Grainger. Parkhearst and Fenton meet in a park where Parkhearst often goes to find, observe, and speak to people: to accrue “material” for his potential—but always unwritten—writing. Fenton, on the other hand, writes constantly, scribbling “what he [is] thinking” with no eye toward a possible reader. This dichotomy—between the “successful,” almost automatic writer in Fenton and the impotent, constantly searching Parkhearst—simmers beneath the stories compelling, inexorable narrative. After Parkhearst and Fenton meet, their relationship spurs a series of events that resemble in their movement a dark twist on the Bildungsroman, in which Fenton’s youth is not nostalgically passed by, but instead made profoundly “superfluous, as age to a god.”

Like “63: Dream Palace,” many of the Purdy’s stories offer a twist on the familiar. In “Mud Toe the Cannibal,” Purdy coopts the form of a fairy tale or fable to offer a brilliant parable for the violence lurking within the apparently civilized. “How I Became A Shadow,” another dark coming-of-age story, spoofs Purdy’s own chosen medium, the short story, beginning: “How I Became a Shadow, how I live in the defile of mountains, and how I lost my Cock. By Pablo Rangel.” Though the tales vary immensely in style and subject matter, they share a depressing yet satisfying tone: that of people trying to stifle their terrified, hysterical laughter. Purdy’s characters drift about seemingly traumatized, aware of the injustice and cruelty surrounding them, even as they seek out others who share their same fears and hope to make tender connections.

“Sermon,” first published in 1961, represents something like a key for interpreting the array of narratives contained within The Complete Stories. Presented as the transcript of a monologue delivered by a figure whose identity is only revealed in the final word of the story, “Sermon” lays out a possible articulation of how Purdy’s world appears and functions. “You”—member of the audience, you reader—”have been infinitely repulsive to me, and for that I thank you.” For the speaker, and in Purdy’s stories, generally, everything, even history (“the continuous error”), seems to be a mistake. But the speaker is thankful for that disquieting fact, for there is redemption in repulsion, in the possibility of “continuance” in the acceptance of the universe as error. One can alleviate anxiety by looking to “be without trying to be,” by orienting oneself against “improvement,” by moving, paradoxically, toward a kind of stillness.

Purdy’s strange tales of depressed pariahs and alienating suburbs aren’t for everyone. His stories tend to describe people and places that comprise peripheries, fringes; with Purdy, we learn the edges of things. The Complete Stories serves as a valuable introduction to his unique mix of desire and disquietude.