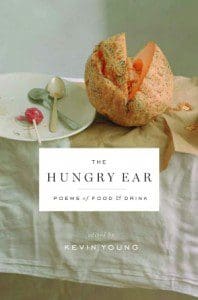

The need for food and drink is universal. The preparation and partaking of meals mark events ordinary and extraordinary. Because of this, food has naturally found itself a subject of poetry for as long as can be remembered. Celebrating the many facets of food and drink, poet Kevin Young, author of seven books of poetry and editor of six previous anthologies, has compiled The Hungry Ear: Poems of Food & Drink (Bloomsbury, 336 pages).

The need for food and drink is universal. The preparation and partaking of meals mark events ordinary and extraordinary. Because of this, food has naturally found itself a subject of poetry for as long as can be remembered. Celebrating the many facets of food and drink, poet Kevin Young, author of seven books of poetry and editor of six previous anthologies, has compiled The Hungry Ear: Poems of Food & Drink (Bloomsbury, 336 pages).

In his introduction, Young writes, “Love, satisfaction, trouble, death, pleasure, work, sex, memory, celebration, hunger, desire, loss, laughter, even salvation: to all these things food can provide a prelude; or comfort after; and sometimes a handy substitute for. It often seems food is a metaphor for most anything, from justice to joy.” The poems that follow certainly demonstrate this all-encompassing nature of food and drink. Divided into four sections, named for each of the four seasons, The Hungry Ear delivers verse for life’s ups and downs, from poets such as Li Po, Robert Frost, Charles Baudelaire, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and dozens more.

There is goodness to be found in the act of eating. In Charles Reznikoff’s “Te Deum,” we read of the satisfaction of “the day’s work done,” so long as the day concludes in sitting “at the common table.” Inversely, through food, we can also dwell on pains and hardships, as Campbell McGrath does in “Woe,” in which he writes, “Consider the human capacity for suffering… the sandwiches at Subway/suck.”

Food poetry can portray the painful truth of inevitable loss, as Seamus Heaney, in “Blackberry-Picking,” laments that “Once off the bush/The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.” Yet food also has the ability to uniquely memorialize the passed life of a loved one. In Donald Hall’s “Maple Syrup,” he writes of “the sweetness preserved, of a dead man/in the kitchen he left/when his body slid/like anyone’s into the ground.”

Most importantly, The Hungry Ear teaches that food, much like poetry, brings people together, through both space and time. Lucille Clifton’s “cutting greens” meditates on the power of an everyday kitchen chore to remind us of “the bond of live things everywhere.”And in Dorianne Laux’s “A Short History of the Apple,” a fruit is the strand that connects human experience through the ages, from “Eve’s knees ground in the dirt/of paradise,” to “Newton watching/gravity happen,” to “Oh Westward/Expansion. Apple pie. American/as. Hard cider.”

Young’s poetry selections also show this truth of unity on a smaller and more intimate scale. In Wyn Cooper’s “Fun,” we read of two stranger bonding, if only for a moment, as they day drink together. And in Heaney’s “Clearances,” the speaker finds special intimacy with his companion over the act of potato peeling. “(N)ever closer the rest of our lives,” he shares.

Food even speaks to us in loneliness. When community with others seems impossible, communion between an individual and a meal itself can be had. The speaker of Billy Collins’s “The Fish” finds comfort in dining alone, as the cooked fish looks up from its platter “not only with chilled wine/and lemon slices but with compassion and sorrow.”

Through reflections on food and drink, the poets of The Hungry Ear bring readers to the varying truths of the human experience, but they clearly take joy in the sight, smell and even sound of food itself. In The Hungry Ear, Kevin Young nicely reminds us of poetry’s capacity to celebrate every aspect of our lives.