Probably the most enjoyable theme through all of John Brandon’s novels is his fascination with people in solitude, because it allows Brandon to linger on often-bizarre penchants and lifestyles.

Probably the most enjoyable theme through all of John Brandon’s novels is his fascination with people in solitude, because it allows Brandon to linger on often-bizarre penchants and lifestyles.

In Arkansas we saw the partnership of Swin Ruiz and Kyle Ribb, two young guys whose utter weirdness in personality lands them in the drug running business. In Citrus County, he focused on the dark longings of his characters, which they ponder on long walks through the forest, or during detention in an undecorated middle-school classroom.

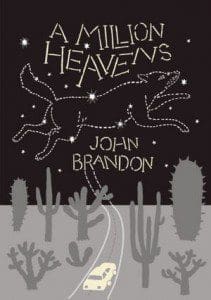

In his new novel, A Million Heavens (McSweeney’s; 272 pages), Brandon maintains his interest in the individual while the desert setting casts their dilemmas in relief. His characters’ lives (and in one case, afterlife) are loosely connected by the inexplicable coma of a young piano prodigy, Soren, whose condition prompts a weekly vigil below his hospital window. Soren’s father, the vigilers, and the other residents of Lofte, New Mexico, are “stranded in the desert,” “above them…a moon that was also a desert.”

Brandon deftly orients his readers to the level of his characters by perfectly evoking the everyday emotions, urges, and annoyances that are relatable despite the uncommon situations they are born of. After some weeks living in the hospital room, Soren’s father’s “back had begun to ache from the orange-upholstered armchair in the clinic room, but going out and locating a store and talking to a salesman and choosing and purchasing his own chair and having it brought up to his son’s room on the 6th floor was not something he was going to do.” Soren’s father has reduced his life to sitting and waiting in a hospital room, and seems reluctant to spur himself to action. Instead, like so many others in the desert of New Mexico, he spends most of his time thinking.

The middle-aged Mayor Cabrera contemplates his life outside of the Javelina Motel, of which he is the manager. He finally “forced himself to remember when Cecelia [his niece] was a baby, when his sister-in-law was herself, when [his] wife was alive.” Though Mayor Cabrera views the desert as “a hostile maze,” its loneliness compels him to reckon with the most painful memories of his past and gives him the opportunity to make amends. The desert’s unavoidable isolation strips Brandon’s characters of their sense of things, so each must ultimately face himself. Like Arn, the archetype of a life in solitude, they don’t have “anyone to answer to.” That is, no one but themselves.

Even the wise and seemingly immortal wolf comes to question the routine that constitutes his existence. In the novel’s first pages, Brandon assures us that “The wolf had been trained by his instincts, by forefathers he’d never known.” However, once he comes across the vigil, which he finds unexpected and inscrutable, the structure of his “rounds” begins to crumble and he no longer finds satisfaction in the familiar.

Brandon’s biggest achievement in A Million Heavens is how he evenly distributes his attention to the poignant stories of all of his characters. At no point in the novel does it feel as if one has too much about Cecelia’s revenge-fueled destruction, the gas station owner’s strange insights, or the wolf’s spiral into violence, just to name a few narratives. The trauma of isolation, life in the desert, and the departure from the quotidian experience falls heavily on Brandon’s characters, but they manage to cope. They forge on with their lives, each commanding attention, and perhaps most importantly, empathy.