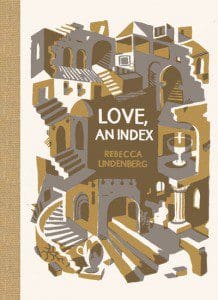

Many poems of love loss have been written, but none are as difficult to categorize as those in Rebecca Lindenberg’s collection Love, an Index (McSweeney’s; 96 pages). The title itself is a teasing, post-romantic gesture, as though the subject can be summed up in one sequential arrangement. And yet, the poet attempts. But unlike Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” whose world is full of “many things… filled with the intent / to be lost that their loss is no disaster,” Lindenberg’s poems do not possess that self-consoling bravado. Her loss is abrupt and unforeseeable; her lover-poet, Craig Arnold, mysteriously vanishes while hiking a volcano in Japan.

Many poems of love loss have been written, but none are as difficult to categorize as those in Rebecca Lindenberg’s collection Love, an Index (McSweeney’s; 96 pages). The title itself is a teasing, post-romantic gesture, as though the subject can be summed up in one sequential arrangement. And yet, the poet attempts. But unlike Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” whose world is full of “many things… filled with the intent / to be lost that their loss is no disaster,” Lindenberg’s poems do not possess that self-consoling bravado. Her loss is abrupt and unforeseeable; her lover-poet, Craig Arnold, mysteriously vanishes while hiking a volcano in Japan.

Whereas Bishop is soberly enterprising in her compilation of losses, Lindenberg is prudent. Her poems cautiously interact with memory: “I do not believe I remember any of this wrong, but there is reason I have left bits out.” One might say she is a curator and a synthesizer of experience, a specialist rather than a generalist, for she chooses particular scenes, times, places, and poets who give voice to her emotions. Lindenberg effortlessly creates an egoless world, full of feeling yet devoid of melodrama, in which she plays sidekick to the more famous Arnold.

This is not diffidence, as Lindenberg’s poems demonstrate enormous range, formally, spatially, emotionally, and with regard to content. The collection’s tripartite division is an exhibition of the poet’s vast reach, which creates room for her to fully commemorate Arnold’s particularity of being, and to infuse the relationship they had with emotion and expectation and thorough-seeing. Simultaneously, it shows the need to compartmentalize experience.

In the book’s first part, Craig is “beautiful as a telephone, colors / of bone, rocket ship, and cocktail lounge,” and he is a “Tall, tall, tall, tall, tall man” and “seduction” and “unfinished argument” and “brooding,” a man whose heart is “a trapdoor.” These poems are the heartbeat of the titular poem, which—situated dead center in the collection—is the heart of the book. The last part, then, involves quiet acquiescence, for the poet must learn to release “ ‘our beloveds kindly into [death’s] care’.”

Lindenberg, meanwhile, situates herself in a solitary and elegiac place that nevertheless seems omnipresent, and encompasses the duration of her relationship with Craig. She is a reservoir of restlessness, bereavement, and reaching. Reaching, for everything, and ultimately, for nothing.

Reading Love, an Index, a question that kept coming up for me again and again was, What is pain to someone whose lover is not just lost but also nowhere to be found? The lover is a constantly appearing mirage, an overlay over reality that makes grieving excruciating, and turns conversation into a raw reminder of one’s aloneness: “at times I want to ask you if you remember this the same way but when I try to imagine what you’d say I find it’s like trying to play both sides of a chessboard.”

Lindenberg so scrupulously handles the trauma of unexpected loss and the hollowness of her deprivation that one feels the full impact of that disappearance and the haunting silence in that grinding halt. But there is intimacy and humor, too, and revelation. Quoting Breton, she writes, “ ‘What I have loved, whether / I have kept it or not, I shall love forever’,” and elsewhere, “if you can recall how it felt at the time you can grasp that the end changes nothing.” This collection rips the reader apart and makes her angry at life’s furtive encroachments. More, it ensures that Lindenberg is no mere sidekick but a poet of immense power, who moves one to feel her heart break and to be humbled before her endurance.