Adrian Wong’s three sculptural works comprising Orange Peel, Harbor Seal, Hyperreal, now on display at the Chinese Cultural Center in San Francisco, would likely not exist if it weren’t for a bit of stubbornness on Wong’s part: his refusal to own a smart phone.

The accomplished young artist and academic, who splits his time between Hong Kong and Los Angeles, excels at a deliberate kind of urban wandering—one that involves scrupulous attention to a city’s spatial organization, architectural forms, and idiosyncratic stylistic details. It also means frequently getting lost. Having the option to mediate his experience through the two-dimensional layer of a GPS map would ruin things, Wong explained. The city is a layered enough place, culturally and physically, as it is.

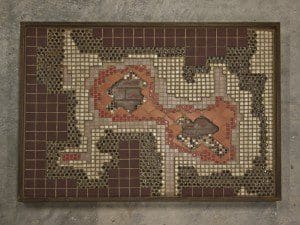

Layers make for a good and obvious formal starting point in analyzing Orange Peel, Harbor Seal, Hyperreal. The show’s main works introduce stratified specimens of three decorative motifs—ceramic tiling, carpet, and metal grates—that hold a special place in the stylings of Hong Kong and of San Francisco’s Chinatown alike.

In the gallery’s first section, two wall-mounted counter-reliefs expose several strata of ceramic tiling. The work has a specific referent; namely, a Hong Kong alleyway, the walls of which have been tiled over again and again in a regular succession of hasty urban renewal efforts. After decades of addition, the width of the passage has narrowed noticeably, placing aesthetics and functionality in humorously overt opposition, as well as creating a public time capsule of sorts. Where weathering has taken its toll on the alley’s already shoddy plaster, Wong recounts, you can literally stick your arm through history.

Beyond this anecdotal significance, the work alludes to a larger cultural interest in peeling back, so to speak, stylistic layers, in hopes of reclaiming a sense of history or authenticity. The appeal of a TV show like Mad Men, for example, lays largely in the series’ detailed excavation of the stylings of the 1960s. On a more literal level, cosmopolitan urbanites have come to prize a partially de-layered aesthetic in interior spaces. Modeled after the exposed brick and rafters of Manhattan’s SoHo lofts, approximations are now produced and exported to outfit trendy restaurants and workplaces the world over.

The grates and tile walls around Kearny Street in San Francisco can be seen as similarly phony simulacra—shiny new replicas of Hong Kong’s distinctive, time-worn aesthetic (which was itself, interestingly, a product of both Eastern and Western influence in the previously British-ruled territory). At the same time, Wong sees the open avowal of this nostalgic intention, a hallmark of the Chinese diaspora, as conferring an idiosyncratic honesty and authenticity to the ornamentation.

Do not expect Wong’s sculptures to articulate all of this conceptual heft; the show is too small for that. The same goes for expecting the works to express their anecdotal significances. Wong’s carpet excavations (similar to the tile pieces, but planted on the floor in what look like archaeological dig sites) are inspired by the tracks his aging grandmother wore into the carpet of his childhood home once she wasn’t strong enough to lift her feet. However, that somber piece of information, important as it is to the work, is not exactly extractable from the object itself.

Hence, a casual visitor who has not been to Hong Kong is most likely to encounter a room of fairly quiet, if formally poetic objects. But with the benefit of Wong’s singular focus, these objects hint at their significance by reflecting certain meaningful but often unnoticed features of the historic streets outside the gallery. At the very least, they are an argument for ditching the Google map, getting lost, and seeing what exteriors an urban space projects, and what may be worth peeling back.

Adrian Wong’s Orange Peel, Harbor Seal, Hyperreal runs through August 25 at the Chinese Cultural Center, 750 Kearny St., 3rd Floor (inside the Hilton Hotel).

The rooms in the Phantoms of Asia gallery have linoleum tiles reminiscent of Chinese restaurants. The display of ceramics looks more like serving plates for a banquet. Was this intentional? The ceremonial history of the objects seems to have been lost by the cramped and noisy spaces, which are next to a videotaped night time soccer game.