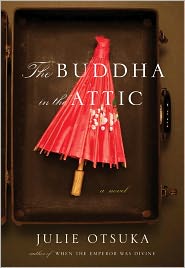

A few weeks back The New York Times book critic Dwight Garner wrote an essay for the Riff section of the magazine titled “Dear Important Novelists: Be Less Like Moses and More Like Howard Cosell.” Essentially, Garner wants important novelists to write faster, to be less like Moses “handing down the granite tablets every decade or so to a bemused and stooped populace” and more like “color commentators, sifting through the emotional, sexual and intellectual detritus of how we live today.” The essay ends with a warning to these important novelists: “If you and your peers wish to regain a prominent place in the culture, one novel a decade isn’t going to cut it.” One might take Garner to task for his rather narrow view of literature-as-sieve (similar to Jonathan Dee’s assertion that “a novel is a document of consciousness”) or for pressuring authors to write beyond their abilities, but the aspect of the piece I found most objectionable was its focus on big important novelists writing big books. By framing the argument as a choice between Moseses (Jonathan Franzen, Jeffery Eugenidies, David Foster Wallace, Donna Tartt) and Cosells (Joyce Carol Oates, John Updike, Saul Bellow) Garner bypasses a whole swath of writers: those craft-conscious gem polishers such as Julie Otsuka, whose second novel, The Buddha in the Attic, was just named a finalist for the National Book Award.

A few weeks back The New York Times book critic Dwight Garner wrote an essay for the Riff section of the magazine titled “Dear Important Novelists: Be Less Like Moses and More Like Howard Cosell.” Essentially, Garner wants important novelists to write faster, to be less like Moses “handing down the granite tablets every decade or so to a bemused and stooped populace” and more like “color commentators, sifting through the emotional, sexual and intellectual detritus of how we live today.” The essay ends with a warning to these important novelists: “If you and your peers wish to regain a prominent place in the culture, one novel a decade isn’t going to cut it.” One might take Garner to task for his rather narrow view of literature-as-sieve (similar to Jonathan Dee’s assertion that “a novel is a document of consciousness”) or for pressuring authors to write beyond their abilities, but the aspect of the piece I found most objectionable was its focus on big important novelists writing big books. By framing the argument as a choice between Moseses (Jonathan Franzen, Jeffery Eugenidies, David Foster Wallace, Donna Tartt) and Cosells (Joyce Carol Oates, John Updike, Saul Bellow) Garner bypasses a whole swath of writers: those craft-conscious gem polishers such as Julie Otsuka, whose second novel, The Buddha in the Attic, was just named a finalist for the National Book Award.

Weighing in at fewer than 130 pages, The Buddha in the Attic is, first and foremost, a work of incantatory beauty. Told mostly in the first-person plural, the novel narrates the stories of a group of Japanese “picture brides,” brought to the United States in the early twentieth century to marry Japanese American men they had never before met. “On the boat we were mostly virgins,” the book begins. “We had long black hair and flat wide feet and we were not very tall.” In the hands of a less skillful writer, the first-person plural might become a kind of crutch or pose. Otsuka, however, handles the form with the deft and simple care of a master craftswoman. In her hands, the first-person plural becomes a perfect medium for conveying the multifarious experience of the picture brides.

The novel traces a loose narrative arc, from consummation to childbirth and motherhood, from the “bunkhouses at the Fair Ranch in Yolo” to the “tiny, curtained-off room at the back of the Royal Hand Laundry” and “the servants quarters of the big houses in Atherton and Berkeley.” Lingering every so often into a small vignette about hostile neighbors, a difficult birth, or a boss’ unwanted advances, Otsuka creates a kaleidoscope of tiny yet exquisite stories. Each is no more than a few sentences, but a few sentences can contain worlds. Take for example, this vignette from the “Babies” section: “We gave birth to Tameji, who looked just like our brother, and stared into his face with joy. Oh, it’s you!” Or this, from the “Traitors” section, which deals with the period leading up to internment: “Chiyomi’s husband began going to sleep with his clothes on, just in case tonight was the night. Because the most shameful thing, he had told her, would be to be taken away in his pajamas.”

In the past ten years Otsuka’s first novel, When the Emperor Was Divine, has already become a favorite text in high school classrooms and college seminars. To watch the book catching on with teachers and students, The New York Times marveled, “is to grasp what must have happened at the outset for novels like Lord of the Flies or To Kill a Mockingbird or A Separate Peace. There was a time when they, too, were just being discovered, just finding their way into what might be called the canon of scholastic literature.” It’s easy to imagine The Buddha in the Attic catching on in this same way. Julie Otsuka may not be featured on the cover of Time Magazine, her face may not grace any billboards in Times Square, but her books will likely be read, discussed, and cherished many years down the road, when Freedom and The Marriage Plot may well be forgotten.

Michael David Lukas is the author of the novel The Oracle of Stamboul (Harper Perennial), which was recently released in paperback.