A dozen museums dot the city center in Trondheim, Norway. There’s the Museum of Decorative Arts, the Tramway Museum, and the Norwegian Resistance museum, which favors dioramas—plastic destroyers, cotton balls painted black. Downtown is a peninsula, tacked to the mainland with spidery bridges. Cranes swing out over the canals from the tops of boxy warehouses. The buildings, even the new ones, are all in the same style—wide and low painted clapboard boxes, in colors at once saturated and muted: poppy red, ocher, mustard, powder blue, and sage. It has a more vibrant art scene than you would expect in a city of about 175,000 souls: more galleries than you can shake a salted fish at. The current installation at Trondheim Kunstmuseum — “sacro e profano,” which in Italian means, of course, “sacred and profane” (in Norse it’d be hellig og profan) — comprises fifteen paintings and three sculptures by local artist Marius Amdam.

The first thing you notice as you begin to move about the installation is texture: Amdam’s not afraid of it. The second painting clockwise from the entrance, “stor våt hund i øyekroken” (“big wet dog in the corner of my eye,” according to Google Translate), depicts a skeleton dripping with gold jewelry. At the bottom of the panel is a crusted wad of black paint so thick it sticks out from the canvas like a shelf. The next panel, “just like honey,” is three-dimensional in a more subtle way. The canvas is three-quarters filled with a pale, feminine face, her expression vacant and almost moronic, like a still frame of Clara Bow or an anime princess. She wears an impressive, powdery-white, Marie Antoinette updo. Inky tears spill from her enormous eyes. At her throat, a chain of loops and whirls draws the eye downward and to the left. There’s something irresistible about the necklace—you can’t stop looking at it. From a distance it looks like old bronze; up close, you can see that the chain is made up of three-dimensional hoops of black, purple, orange, and mud-colored paint, washed with a thin coat of white that shows brightly against the turbulent colors beneath it, giving an overall look of burnished metal.

The strands of her hair are thick ropes of red, orange, and pink paint, similarly brushed with white. Amdam paints on paint; the paint is both being delivered and delivering at the same time, both medium and mass. From a distance, the figures look wavy, distorted—as if instead of stroking inch-thick swaths of paint onto the canvas, Amdam left a two-dimensional painting in the rain, letting it warp like floorboards. The pile of hair reminds one of the icing on the tempting cakes in the bakery windows here. Indeed, it is almost impossible to talk about “sacro e profano” without recourse to words like smear, streak, blob, daub, and spurt. The metaphors that come most readily to mind are edible and bodily—frosting, whipped cream, Kaviar (a salmon pink, fish-flavored mayonnaise Norwegians gobble up with Wasa crackers. It comes in a serious-looking metal tube and resembles nothing so much as acrylic paint, unless it’s industrial strength glue), and also excrement, vomit, semen. These sections of the canvasses are full of tension, pressure—a large amount of matter forced through a small space. It’s almost as though you can feel the painter clenching his fist. By contrast, the two-dimensional spaces in the paintings seem limpid and restful—such as in “just like honey,” where mottled lavender squids float placidly on a sage-and-smoke background checked with yellow.

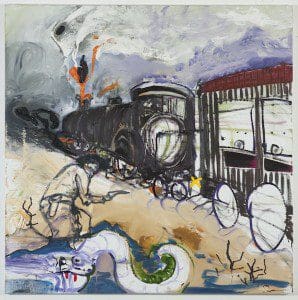

Continuing clockwise around the installation, we come to a series called “gunslinger ballads and trail songs,” which reads as a genuine homage to the iconography of the Old West—bleached skulls, red skies, and the terror of masked men. Second in the series is “the great train robbery,” complete with engine and bandit, and a foregrounded skull with long, curling purple horns. The train is a child’s crayon drawing, indistinct, all colors—but Amdam still manages to suggest the window shades in the passenger car, complete with hand-pulls. The inside of the car is a slice of magenta-tinged black under the blinds. The engine stack spouts orange fire, wooly white steam. Thick black smoke spills from under the wheels. The robber is the least menacing figure in the painting, and almost looks stuck there by accident, his gun unconvincingly drawn, his form insubstantial, the merest outline compared with the train, the landscape. What’s he doing here, in the American West? Doesn’t he know his great train robbery is proceeding without him in Victorian England, right on schedule?

Included in this series is, maybe, the most mystical painting in the installation, another literary title: “blood meridian.” A black-robed, skull-faced figure wears a flat hat with puff-balls dangling from the brim. A background of star-streaked, light-washed black is pierced by seemingly random fuchsia lines, almost suggesting constellation diagrams. Look closer and your realize that the lines actually circumscribe the dark figure, passing behind and in front of it, giving rise to a shaky frame, partly collapsed, some of the lines leaning away into nothing. Though the skull has none of the exuberant hilarity of Day of the Dead art, there is something grimly humorous about the figure, about the fussiness of his hat. Skulls appear in nearly every painting in “sacro e profano,” sometimes on top of skeletons, sometimes pinned to a scarf or tucked into a hairdo. Indeed, the only element that crops up with equal consistency in Amdam’s work is the engorged male member, which brings us to the title piece, across the gallery from the Western tetrad—“sacro e profano.”

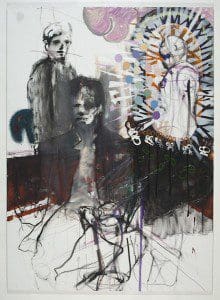

At the top right is an oval of yellowish green, brown and blue, slashed with white rays, surrounding an obscure figure—little more than a circle over a semi-oval, a head on rounded shoulders. It looks like a mechanical gypsy in a fortune-telling booth, or an icon. Arching above the oval and disappearing into the top of the canvas is what can only be called a giant, bubble-gum pink phallus. Two figures to the right of the icon are suggested (more than rendered) by soft black lines and scraped-thin shadows. One carries a blue horseshoe dotted with colors that might be an artist’s palette. The other, foregrounded, in a sitting posture, wears some sort of jacket, perhaps an old-fashioned high-collared coat and cravat, and nothing else. The right thigh is rendered beautifully—voluptuous and effortlessly proportionate—with only a couple of lines. It’s all a little jokey, as though Amdam is daring us to think the obscure figure in the cupboard is sacred, the exposed male genitalia profane, and the figure with the palette the artist. Or perhaps it’s a rueful admission that he doesn’t really know what these words mean, or where one ends and the other begins. Maybe, for Amdam, they are inseparable; maybe he can’t draw an icon without surrounding it with penises, and vice versa.

After “sacro e profano,” the paintings take a sharp turn for the darker, and Amdam goes further into his globular vein. The face of the central figure in “ekspedisjonsleder ved trondheim kemnerkontor / ser nordlys og stjerner / i det hun besvarer min korrespondanse / med blomster hun har fått som / månedens arbeider” (Google says: “expedition leader at Trondhiem treasurer’s office sees the northern lights and stars as she answers my correspondence with flowers she received for a month’s work”) looks like it’s melting, Raiders of the Lost Ark-style. One of its three possible eyes has oozed down to lodge greasily below its nose. Its mouth is a vivid hell—a thick red line, an open capital C, fringed with festering purple gums. Sharp white dabs make eight awful teeth. A sickly rainbow vortex spews from the mouth of the creature, which looks to be howling and vomiting at the same time. These lines continue in an upward sweep, becoming more vaporous as they go, joining a streak of recycling bin green and meeting pale pink clouds before swirling down again to connect with the figure’s bare backside in an ugly, rooted tail. It’s an ouroboros of filth.

In the first circuit around the room, you might be tempted to skip the first painting, “vanligheten” (“regular public”), but after the sticky violence of the final three (which are not, however, without a certain messy glee), it’s a relief to return to this one, which is so different from everything else in the installation. Whimsical, calmly colored. Sinister, too—those black vines twining toward the family from the edges of the canvas, the cat’s ghostly claws, the mother’s staring eye—but in a subtle, brooding way that feels like a respite (no respite, though, from the omnipresent phallus, which intrudes from the left side of the panel). There’s something deeply touching about the face of the little boy on the right. Something about the coloration—the three blue dots in the upper right-hand corner, the two maroon flecks that might be nostrils—makes you search the face, again and again, looking for his eyes.