I could tell the performance I was about to witness late last month was extraordinary even before entering the auditorium, just from watching the audience trickle into Z Space in San Francisco. There was a man who had somehow fused his beard with a slinky-like spiral pipe and wrapped it around his neck like a scarf. There were a few women in Betty Page/rockabilly outfits and the attendant shellacked beehive and Winehouse eyeliner. One girl’s hair resembled a Pantone swatch sheet—literally—small squares of dye checkered her shoulder-length crop. One man, who we found out later was the set designer for the production, had sausage links hanging from his belt loops. There were leather and piles of silver, feathers and dreadlocks, tattoos and guy-liner. I’ve never felt like such a square; even before the performance began it had rendered my life meaningless.

As a prelude to Bad Unkl Sista’s latest production, “First Breath, Last Breath,” the performers proceeded into the lobby—slowly, staring at the audience, making gong noises on obscure instruments—before moving into the proscenium theater space. The procession gave the audience something the performance could not. Up close we could see the magnificently bizarre costumes devised by artistic director, choreographer, and soloist Anastazia Louise. It was a head-scratching amalgam of Victoriana, Burning Man, and Steampunk: gas masks, fishbowl mouthpieces, hoop skirts of shredded denim, toreador and Japanese hakama pants, Puritan bonnets, and of course the signature white full-body paint of Butoh.

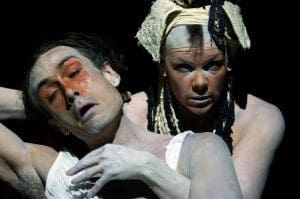

What we could also see better in the procession than from the stage were the facial expressions of the performers (although they were by no means unreadable from the distance). These expressions reflect an integral characteristic of Butoh, which rejects the dictate of traditional showmanship that a performer must put his “best face” forward. Butoh revels in death and the grotesque aspects of living. The performers walked shivering and hunched over, their eyes rolled back, jaws hanging open and tongues dangling, heads lolling to the side, hands trembling. This overture was particularly powerful when one realized how seldom we witness the human body in this condition: only in the presence of someone very sick, damaged, or deranged.

Though many of the acts showcased skills that only the most hale could execute, this preoccupation with decline remained a motif throughout “First Breath, Last Breath.” Kristen Greco shook and coughed, her white face smeared with fever-strong blush. Michael Curran, a dancer with a Pierrot face and Kowalski body, contorted his limbs and spine in a series of poses which might have appeared as a standard circus act. But his face never lost its expression of melancholy, and this contrast between action and expression nicely complicated his act.

Karl Gillick, whose torso, tragic brow, and beard recall the ancients’ boxer statues, infused his aerial silk act with an emotion that made a beautiful paradox out of what could have been a familiar acrobatics act. Most of us regard the ability to fly as a great “what if?” We associate dreams in which we can fly with bliss and freedom. Garrick’s apparent wistfulness was, in this context, provocative and beautiful.

In perhaps the most narratively straightforward piece of the night, Shannon Gray Collier was wheeled onstage in a wheelchair, feet in casts, pestered and restrained by her cohort assuming roles reminiscent of Nurse Ratched. With a gasp, Collier grabbed onto an aerial apparatus that had been lowered before her, and, clinging to it as it rose, transformed from a suffering, immobile waif to a graceful, ethereal air dancer. As the trapeze again lowered to earth, so did she, and the diminution of her ephemeral but transcendent powers was heartbreaking to witness.

Periodically, the performers employed the Butoh motif of the “silent scream,” and lurched, cringed, and trembled between fits of more robust physicality. There is a debate (or maybe it is merely a Western misperception, likely based on American guilt) whether Butoh—which emerged in the years following World War II, and which its practitioners insist developed as a response to the student protests of the ‘60s—grew out of the horrors of the atomic bomb. Indeed, the emphasis on withered mobility and deformity, the suggestion of physical and mental trauma, even the white body paint (which also echoes images of people covered in the white dust on 9/11), all make a case for correlation, however inaccurate. But even disregarding the spurious connection, it was sometimes difficult to watch the performers enact these vignettes. It wasn’t always clear whether this was a triumph against suffering—art born of devastation—or a fetishizing of the same. Perhaps that ambivalence is part of the purpose.

Other elements were also hard to gauge. It seemed at times, that as with some other Japanese art forms, to appreciate it one had to alter one’s mode of watching, to become a connoisseur of slowness, to develop an eagle eye for the subtlest expressions and movements. By standards of Western stagecraft, certain movements were too minimalistic to justify the spareness of the moments leading up to them—to watch a woman creep across the stage, lift an elbow, and continue creeping requires a threshold for boredom that other performance art forms don’t dare challenge.

To a perception shaped by the more expansive European dramatic arts, certain moments throughout “First Breath, Last Breath” verged on self-indulgent. But this might be a characteristic of the art form that can’t be judged fairly by criteria developed outside the culture that created it. Most of those moments were created by Louise, who was possibly the least “showy” dancer (again, this might be a virtue in Butoh). Other performers would be executing some dazzling feat of acrobatics, and at some point, Louise would attach herself to them like a gremlin, putting the kibosh on their more spectacular movements, and the presentation would suddenly narrow once again to creeping, cringing, grimacing, and hugging. In Louise’s solo piece, it was hard to stay focused on her subtleties while musician Goyo Aranaga accompanied her with kargyraa throat singing, reddening in the face, swelling through his neck, and sounding something like a human didgeridoo.

However, the aspects of Bad Unkl Sista’s production that might require a different sort of viewer to appreciate them did not detract from the overall fascination of the work: visually, musically, and dramatically, “First Breath, Last Breath” offered plenty to enjoy in the moment and to ponder afterward. The sheer wealth of weirdness and invention makes one impatient to see what their next extravaganza holds in store.

Bad Unkl Sista performs regularly at Supperclub.

Read more from Larissa Archer at her blog, larissaarcher.com.

One thought on “Soaring in the Air, Writhing on the Ground: Bad Unkl Sista’s ‘First Breath, Last Breath’”