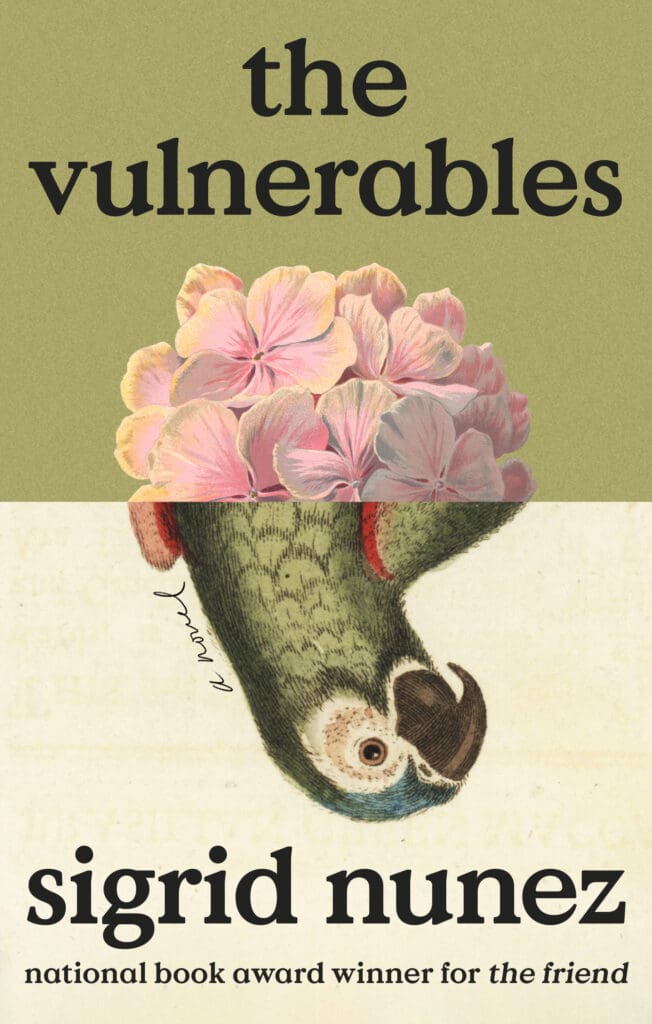

Sketched from memory by a first-person narrator, The Vulnerables (Riverhead; 242 pages) appears at first to be a kind of memoir, the remains of an aging writer’s observations during her time in pandemic-stricken New York. Considering the volume of novels that have emerged from this period, it’s unsurprising that Sigrid Nunez’s most recent book portrays the city as though it were a still-life object, that the narrator ponders her relationships with the gifts of retrospect and distance. Of course the lockdown demanded self-reflection. Of course it resulted in unusual living arrangements with unlikely groups of people. Even the plot is unassuming enough and conforms to this category. The death of the narrator’s friends causes her to reunite with an old group of friends, one of whom asks her for an unusual favor—to move into her friend’s apartment and care for her parrot, Eureka. A week after she does so, the prior caretaker, an attractive New York University undergrad, returns without warning. What is unexpected is the form this story takes.

Throughout the novel, Nunez gestures toward the tenuous and permeable boundaries of writing “truthful” fiction. The narrator names her friends after flowers (the men in the book are named for convenience, as are all the pets). Interspersed with the narrative are sentences that begin in earnest: “I remember when…,” I like when…,” signaling to consider the lens through which she is narrating. Late in the novel, the narrator backtracks, writing, “But right now it feels as if none of this could really have happened, that I must be making it all up.”

We don’t trust her; still, we are entertained. Nunez’s willingness to write directly from life contributes to this sense—rather than narrativizing what transpires in the plot, she writes it as is. She includes statistics the narrator finds about the neighborhood of an old classmate (“Transportation: Poor. Daily Life: Poor. Safety: Poor,” and so on), her stunted attempts at writing (one short piece is titled “Proud Author,” another is “Even Worse”), and a metaphor that she explains she has wanted to use for years but never found a place for (“twelve butterflies out of one caterpillar”). What might have been disorienting and unnecessary is instead a show of impressive control. As is observable in The Friend, Nunez gently nudges the boundaries of her fiction. She becomes an omniscient observer, even as she looks inward.

The lack of a central, unilinear story injects a realism into the novel, as do the vignettes Nunez enters and exits neatly. She peers into the life of naturalist Craig Foster, who bonded with an octopus. She considers the part of Joan Didion’s essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” in which she witnesses a five-year-old on acid. Moments in the narrator’s own life are treated similarly, with short but total devotion. The narrator recounts the story of Olaf, an ex-lover of her friend who died, describing in detail the way he guided his partners through mushroom or mescaline or acid trips. “ ‘And to have Olaf listen to you,” Lily said, “was to know that no one in your life had ever listened to you before.’ ” These tangents live only as long as they need to, and her attention is quickly turned elsewhere. It’s important, she is showing us, not to think too hard, not to dwell on any one of these things too much. The detachment works—the prose operates at a crossroads, at once intimate and removed, full of personal divulgences in anonymized settings. We find ourselves caught off guard by moments of unexpected feeling: when her friend faints just before dying, “she [goes] down like a chopped tree.” She ends the Foster chapter with the sudden declaration, “It was the kind of story that makes me think I should have changed my life. Instead, I have wasted it.”

“You’re a vulnerable,” a younger friend of the narrator scolds. “And you need to act like one.” It feels personal—to the narrator, to Nunez herself, to her friends with their flower names, to the people and animals she ponders, to you. By the end of the novel, you feel for the narrator and the person who wrote her. You want to know if any of it’s true. But then somewhere in the prose is a gentle reminder, and the rug is pulled out from under you—Nunez is, of course, writing fiction. She is under no such obligation.