“Unscrew the locks from the doors! Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!’’ So prophesized Allen Ginsberg long ago, channeling Walt Whitman in the epigraph to “Howl,’’ a literary debut that with time seems ever more distant, yet still completely present. Over the course of his remarkable career, Ginsberg resurrected distinguished predecessors from Whitman to William Blake from the tyranny of schoolbooks. He famously served as guiding light, mentor, and press agent to Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and too many others to mention, bringing the spoken word back into public discourse while remaining at the vital center of political protest, cross-cultural currents, and the mainstreaming of Tibetan Buddhism.

All of which while remaining, ineluctably, Allen, a Jewish boy from Paterson, New Jersey, the landscape memorialized by yet another of his mentors, William Carlos Williams, who preferred working within the American grain to the comparatively weak Europeanized tea of T.S. Eliot—or, for that matter, Ezra Pound. (Characteristically, Ginsberg befriended Pound, even offering him exit strategies for his anti-Semitic views when the two men met in Rapallo, Italy.)

A figure of huge modesty, Ginsberg nevertheless was aware—how could he not be?—of his place in the cultural firmament, and ever sought to use his celebrity to bring about greater awareness, kindness, and humanity to this chronically self-destructive planet.

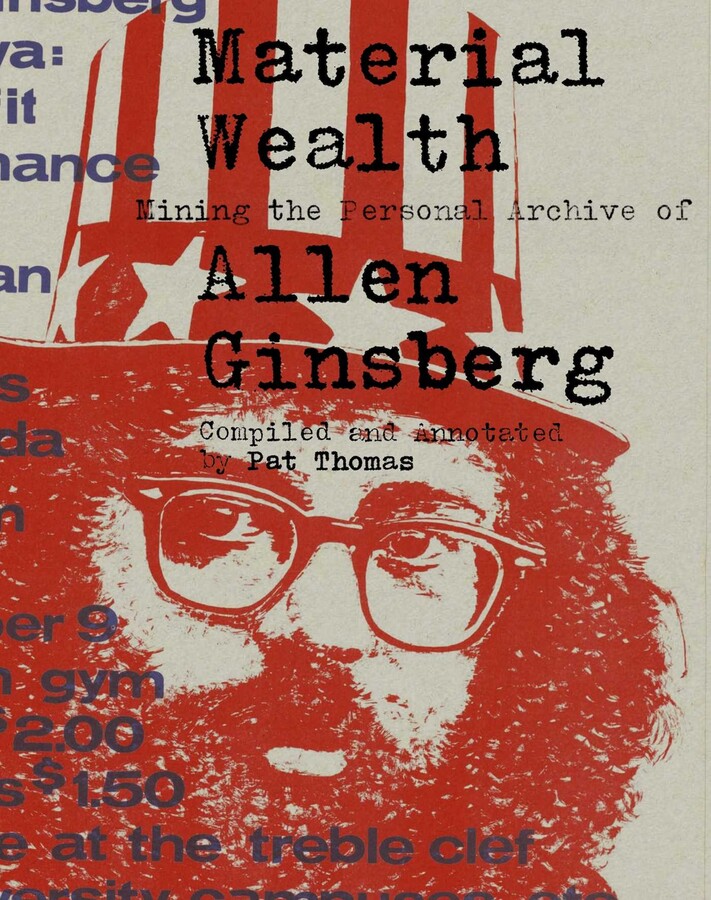

An ambitious new volume, Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg (Powerhouse Books; 256 pages), compiled and edited by Pat Thomas, demonstrates just how committed he was to recording the “minute particulars’’ (again, in Blake’s phrase) of a life of extraordinary range, as well as depth. Culled by Thomas and Peter Hale, photo archivist of the Ginsberg Estate from the multifarious items in the Ginsberg archive acquired by the Stanford University Libraries Department of Special Collections, it’s no small irony that the collection ended up on the West Coast rather than Columbia, where he received a degree in English (minoring in economics!) despite being twice expelled.

The snapshots in time are striking—an image, at the outset, of Ginsberg with a group of Merchant Marine trainees in Sheepshead Bay shows him “second row, third from top,’’ smiling broadly in sharp contrast to fellow recruits who seem intent on emptying any traces of human emotion from their faces. It’s that openness to experience that is displayed throughout.

To his credit, Thomas has tried to break new ground with this treasure of fertile material. As he writes in his introduction, “So much has already been published about Allen’s relationship with his fellow Beats—especially Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs. Rather than regurgitate that for the hundredth time, I’ve taken some paths less explored: Allen’s interactions with Bob Dylan, Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman of the Yippies, Paul McCartney, his anti-Vietnam war protests, including the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago.’’ (He mentions in passing, Ginsberg’s collaboration with McCartney on “A Ballad of American Skeletons,’’ performed at the Royal Albert Hall of “Day in the Life’’ fame—Google it!)

But Thomas does not fail to include memorabilia highlighting his role as advocate, scold, and enthusiast in modern literary history. They include letters to The New York Times berating the editors for a clueless review of Kerouac’s Dr. Sax, sheepish notes from everyone from Jason Epstein’s polite dismissal of Burroughs’ Junkie (initially called “Junk’’) to a Playboy editor iterating the reasons for rejecting a manuscript by his Beat pal, Herbert Huncke: “I fear that the subject matter, a giant junkie who is also a hermaphrodite, would make it unacceptable for the pages of PLAYBOY. As you know, we have few taboos in the magazine, but Mr. Huncke has managed to include almost all of them in his brief article.’’

Other delicious artifacts include a letter—saved by Allen, ever the pack rat—from a North Salinas high school student seeking explications of “Howl,’’ “Reality Sandwiches,’’ and “A Supermarket in California,’’ along with biographical details. “Anytime before May 15 (due date for thesis) would be groovy’’—Ginsberg’s response, if any, is unrecorded.

Henry Miller’s note in response to a request for a Big Sur meet-up is also choice: “I would rather you didn’t come to see me. You have no idea how much I am plagued by visitors. All I crave now is solitude—and time to do my own work.’’

Truth is stranger than fiction. The collection includes a transcript of a call Ginsberg made to Henry Kissinger, apparently at the suggestion of Eugene McCarthy. Ginsberg chides the oleaginous war criminal, courteously: “I gather that you don’t know how to get out of the war’’ and suggests that such a meeting would be most useful “if we could do it naked on television.’’

Other samples in this inspired mash-up include Candy author Terry Southern’s (outlandish) parody of “Howl,’’ complete with obligatory exclamation marks: “The world is fuck! The soul is fuck! The tongue and cock and hand and asshole are fairly closely related to fuck!’’

Downwind, the description of Ginsberg’s attempts to cool things out at the Chicago demonstrations staged by the Yippies in 1968, chanting “Om’’ to the crowd of protesters in Grant Park—something I personally witnessed—is moving, a restorative gesture for an impossible scene.

Back in the Theater of the Absurd, Thomas—previously the author of a book on Jerry Rubin—describes Ginsberg’s doomed attempts to get Dylan involved with Rubin in a Vietnam Day Committee march. “We ought to have it in San Francisco right on Nob Hill where I have my concert and I’ll get a whole bunch of trucks and picket signs,’’ Dylan told the poet, briefly entertaining the notion. “Some of the signs will be blank and some of them will have lemons painted on them and some of them will be watermelon pictures…” The baffled Rubin declined, only embracing the Dada-esque spirit later when he participated in the Levitation of the Pentagon.

Less obliquely, Dylan provided the title for this collection: “Seeing Ginsberg was like going to see the Oracle of Delphi. He didn’t care about material wealth or political power. He was his own kind of king.’’

Material Wealth is beautifully put together, with enough white space to allow the photos and text to breathe. But it shouldn’t be seen as an archaic document for Beat and post-Beat completists. (Let the record reflect that Ginsberg was not stuck in the past—he recorded with the Clash and bought a sandwich for Patti Smith in the East Village when she was a struggling poet.)

The public and private poet merged, sometimes to the consternation of contemporaries like Gary Snyder.

But Ginsberg was not one who hoped his name would be “writ in water.” He welcomed the fame his words garnered—in subway walls, tenement halls and the universities that once snubbed him. He brought poetry back into the conversation, then served, as ever, to justify its electronic amplification from the likes of Dylan or Leonard Cohen. These days, it has once again retreated to the margins, and the singer-songwriters who once seemed like successors have faded, too, along with the hopes for a unitary vision in a hopelessly fractured world.

Lightning in a bottle, indeed. We can only hope that, this time, it strikes twice.

Paul Wilner is a contributing editor at ZYZZYVA.