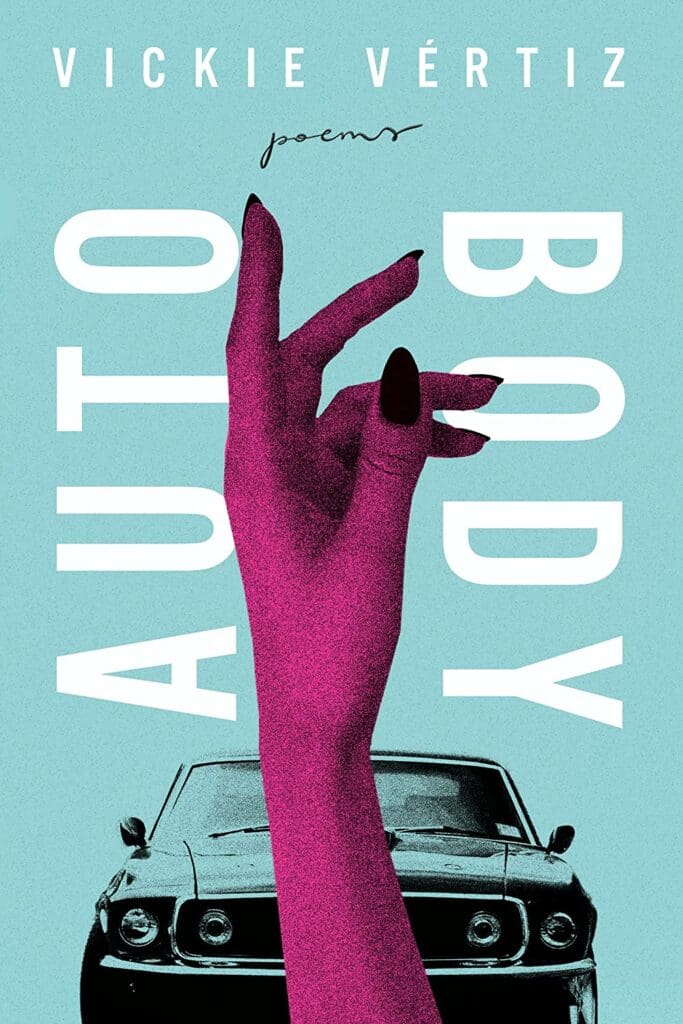

The title of Vickie Vértiz’s latest poetry collection, Auto/Body (90 pages; University of Notre Dame Press), suggests the inner workings of cars, but its focus has to do with the harnessing and distribution of power, personally and societally. Sometimes fueled by rage, sometimes by desire, this power serves as the driving force behind this collection.

Vértiz is a Mexican American poet who teaches at UC Santa Barbara. She divides her book, which won the Ernest Sandeen Prize in Poetry, into three sections: Alternator, Distributor, and Transmission. The first section sets the tone with its sense of righteous anger. In an automobile, an alternator converts chemical energy to electrical energy to charge and replenish the car battery and power other electrical components; this energy glows in “nature armed medicine,” a concrete-form poem shaped by indentation into the silhouette of a large church with a conical steeple, without a cross, or perhaps it’s a California mission. The poem’s content further illuminates this institutional image with unmistakable touchstones of indigenous genocide, running through each line like a current of electricity. It concludes:

We arm

poppies & huitzils & remind you

that

what we have is bigger than what we do not possess

Aman quiahui’ ihuan nochi’ xoxhqui’. Ahora llueve y todo reverdece

The poems in this section are largely bilingual and exploratory in shape—“Disco” is in the form of a half-illuminated disco ball, and the irregular spacing of “I don’t know what else to tell you about t e a r g a s” evokes blurred vision.

This contrasts with Distributor, a section powered by nostalgia. In older engines, the distributor routes electricity from an ignition coil to spark plugs, and these poems mimic that measured approach to their own energy, which permeates each verse.

The poems in Distributor are almost exclusively in English, and the mood often shifts to one of heartache. One example is “Thank You 1-800#s” which begins:

As if making out with Def Leppard

Was any kind of violence

I am watching myself 20 years ago with this guy

My brother’s friend who giggled with some small revenge against who knows who

Transmission, the final section of the book, provides a stable middle ground between the fiery tone of the first section and the melancholic pulse of the second.

The most striking poem here is “Joteria [All the things you forgot to say],” which takes the form of a Bingo card grid. Each box holds a line in its little cage, creating a cell block commentary on joteria—akin to camp—as borne from the mainstream portrayal of queerness as a commodity. This comes across most clearly when a poem’s speaker remarks on the whiteness and straightness/cisgenderism of a TV show hostess who calls her skintight dress “joteria.”

Transmission presents a final question: Given a finite amount of energy, where should we channel our outrage, and how should we conserve our resources? When our bodies begin to fall apart, how can we keep going before reaching our final destination?