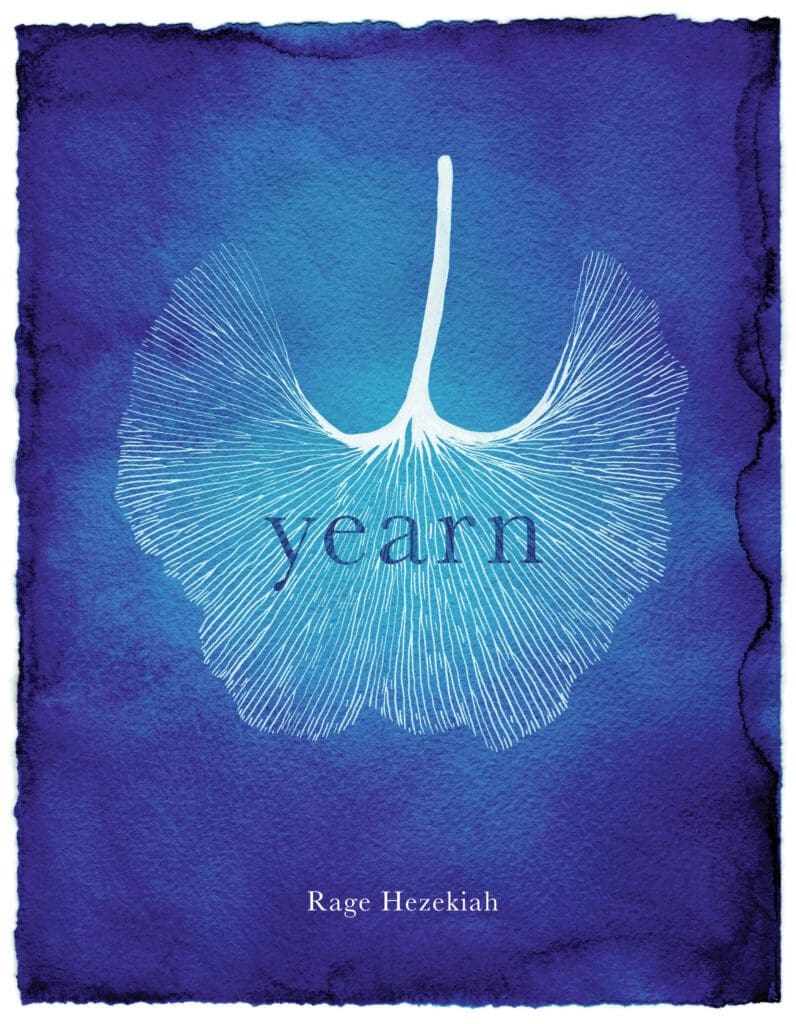

Rage Hezekiah’s Yearn (65 pages; Diode Editions), the winner of Diode’s 2021 Book Contest, makes an active inquiry into notions of bodily autonomy and limitation, resilience, and an evolving sexuality—charting what Nate Marshall describes, in his blurb of the poetry collection, as a stunning exploration of “the erotic, the familial, and the mundane.”

Hezekiah is a New England-based poet and educator and a recipient of Cave Canem, Ragdale Foundation, and MacDowell Colony fellowships. She is the author of the poetry collection Stray Harbor (Finishing Line Press) and the chapbook Unslakable (Paper Nautilus). Her poetry has appeared in the Academy of American Poets Poem-a-Day, The Cincinnati Review, and The Colorado Review, among other journals and anthologies, and she presently serves as Interviews Editor at The Common.

Yearn gathers poems from the past six years of Hezekiah’s writings—two of which, “Northern California” and “Practice,” were published in ZYZZYVA Issue 116. Hezekiah discussed the collection with us via email. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ZYZZYVA: How would you describe the relationship between this new collection, Yearn, and your past works, Unslakable and Stray Harbor?

RAGE HEZEKIAH: I think of Stray Harbor and Unslakable as occupying similar space. The majority of the poems in those volumes were written during my MFA program at Emerson College and were essentially my graduate thesis. I completed my MFA in 2015, and both Stray Harbor and Unslakable were published in 2019, so the collections evolved during that time.

I began working on poems for Yearn in 2016, but the vast majority of the poems in Yearn feel current to me. I was at Ragdale in 2019 to put the finishing touches on Stray Harbor and begin poems for my new body of work. That residency allowed me to spend time writing about my body and my young sexuality. These initial poems helped frame Yearn, which feels bolder to me in its content than Stray Harbor and Unslakable. The last few years have given me the space to be more intentional about studying craft and being more mindful about craft in my work.

Z: Desire is a strong current throughout the poems, shored up in hunger, restraint, and coercion. How would you situate desire in this project, and what inspired you to name the collection “yearn”?

RH: Assembling a collection is such a strange proposition, but when I began putting this book together, I felt as though the body was the dominant theme. I’ve been working with The Common for the past year and a half, and I had the opportunity to attend one of their Master Classes with Vievee Francis and Curtis Bauer last spring. The class was specifically focused on assembling a collection of poetry, and the conversations and exercises in that class helped me view Yearn in a new way.

I’m also fortunate that my wife is a computer whiz, and she wrote a program to determine the most repeated words in the manuscript. This was useful not only to get a sense of the words I was relying on too heavily, but also to help me understand what the collection as a whole was saying. The word that appears most frequently in the manuscript is want. With this information, I thought about the book in terms of how to frame desire effectively, and to consider the range of desires in there.

My three-year struggle with fertility dominated my experience as I crafted the poems for Yearn. As is often true for me, initially I was unable to write about it because I felt too close to the sense of loss and grief, too mired in the struggle to write into that space. Once I started writing about my desperation to start a family and the relentless of that desire, I feel like the book started to take shape.

Z: Why did you decide to organize the poems in three sections, and what do the sections distinguish or give shape to in the collection?

RH: When I’m reading a collection, I revel in the pause that sections bring. While assembling this manuscript, I knew I wanted to try and group the poems to create a sense of containment within the book. Initially, I had grouped the poems thematically, but I found this was a heavy-handed approach, especially with the number of poems about sex and sexuality. When I asked a friend to read an early draft of Yearn, she encouraged me to spread these poems out, and to think about how to weave them throughout in an organic way.

While the goal was to use sections to give shape to the book, this process was mostly intuitive. Something that has been helpful for me in thinking about the collection as a whole is where does the reader start and where do they end. I also considered the arc of my debut collection, Stray Harbor, and its first and last poems to inform where Yearn would start.

The final poem in Stray Harbor is “Our Bike Trip,” a poem about biking through Washington state with a dear friend, and both of us attending a wedding where we made out with men. The last few lines are: “men are so simple/we didn’t know we could have been kissing each other.” I see this poem as a bridge to the first poem in Yearn, “Consent.”

Z: It seems like in Yearn you explore a number of formal approaches: some poems model a consolidated poetic artifice (for example, “On Anger” or “Glimmer”), while others play differently with dispersed text and layout (“Amends,” “Eighth Grade Field Trip”). Could you say more about the formal variety in the writing and what compelled those decisions?

RH: Over the past few years, I’ve deepened my craft and sense of form by reading craft essays and paying attention to the formal approaches of other poets. While most of what happens on the page is instinctual for me, I made intentional choices with form in this collection. The page size (7×9) is a bit larger than many contemporary poetry collections because I wanted to be sure the poems with dispersed text had space to breathe.

I recently watched a recorded craft talk that Camille T. Dungy gave at Bennington College entitled “Ways to be Present.” She spoke about choices we make on the page that can incorporate breath and encourage the reader to have a sense of pause. I thought about this when writing these poems and assembling them on the page. I think one of the biggest challenges I encounter as a poet is merging content and form, and I tried to do these poems justice in this way.

Z: You note that the three poems—“Cento for My Mother,” “Cento for Longing,” and “Cento for Surrender”—are comprised entirely of lines borrowed from other writers, including contemporaries such as Tiana Clark and Meg Day. How do the centos fit into the collection, and what inspired you to bring in others’ language?

RH: Centos seem to be my favorite form, in part because they provide me with language when I’m struggling to find the right words. Reading the work of other poets is a source of inspiration for me, and writing centos feels like getting away with something. I often find that the lines I’m most drawn to in the work of other poets are connected thematically. These common threads make centos an instinctual form.

When I’m reading, I copy lines I love into my notebook or onto index cards. The index card notetaking facilitates my ability to physically arrange lines within a poem to bring the work to fruition. I see the centos as opportunities of pause throughout the book. It’s an honor to stitch the words of other poets into new work.

Z: Many of your poems, like “Sixteen” and “Practice,” speak vividly to experiences of pain and violence. What do you find poetry offers in the way of responding to or voicing pain? What do you think is valuable about poetry as a mode of personal and/or political redress?

RH: Poetry has always been a haven for me, and bringing my pain to the page is one of the primary ways that I heal. I feel liberated by the way poetry provides me a space to name painful or uncomfortable things I’ve experienced, and I’m grateful for access to writing as a tool for recovery. When I began writing poems for Yearn and exploring my early sexuality, I was surprised by the shame and secrecy I felt about some of my early sexual experiences. Giving voice to these experiences helps me surrender my shame. As is often said in recovery, we’re only as sick as our secrets.