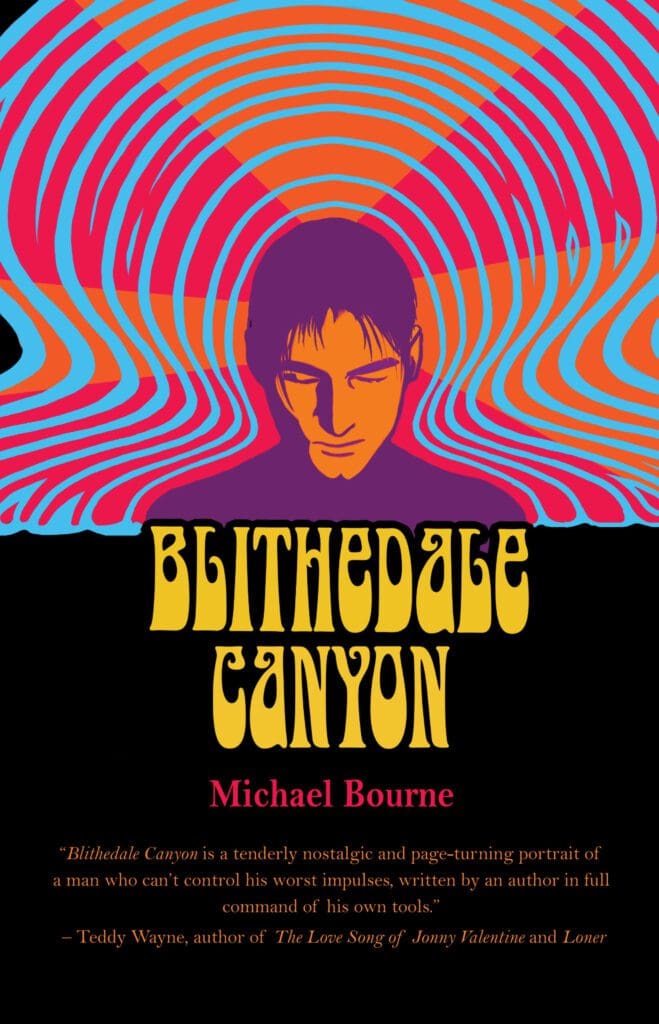

Michael Bourne’s first novel, Blithedale Canyon (292 pages; Regal House Publishing), is in many ways a story about California. It is a treatise on the nature of class in one of Marin County’s wealthiest cities, the psychological costs of gentrification, and the harrowing trials of a young man in the throes of addiction. Bourne finds an unlikely hometown hero in Trent Wolfer, an alcoholic and ex-convict who returns home to Mill Valley following a stint in jail. Trent is twenty-nine years old, flipping hamburgers, and spending his work breaks downing miniature bottles of vodka and gin in his car. Thoughts of returning to Isla Vista—where he dropped out of college and embezzled nearly $50,000 to fund his sex-and-drugs fueled benders—plague him daily. Dutifully, he manages to avoid hopping on the I-5 and instead returns home to his mother and Stan’s (his stepfather) house, where he is served superfood-based smoothies by an in-house chef and housekeeper, watching Stan do yoga on one of the thousands of indigenous-inspired mats and other household items sold at his online, hippie-turned-luxury-homeware store.

This creates a strange kind of cognitive dissonance, one that brings Trent constant discomfort. He remarks, thinking back to his time in jail the year before:

I’d been working so hard to make it look like I wasn’t afraid, like I was cool with watching guys go down on each other in the showers and pick through their own shit for heroin balloons that I had no time to worry that I couldn’t hold a cup of coffee without spilling. Now, I was in Mill Valley, living in one of the wealthiest towns in one of the wealthiest counties in the United States.

Trent’s estimates are accurate: Mill Valley is one of the most affluent and highly educated cities in the U.S., with a median household income of $109,759. A drive through Blithedale Canyon is a near-idyll of Californian living: houses decorated Santa Fe-style with tasteful terracotta accents, the air smelling faintly of honeysuckle and eucalyptus. It would make recovery easier, Trent believes, if the misery he feels going cold-turkey on the inside matched what was going on outside—a not-entirely-unrelatable feeling for those who have ever felt the heightened melancholy of being miserable in a beautiful place.

Bourne successfully evokes this dissonance throughout the novel, as moments of rare calm in Trent’s life become punctuated with chaos. Stan eventually kicks Trent out of the house, but not before setting up a kind of Hail Mary job interview with the neighborhood grocery store. With bated breath, Trent’s mother buys him a new suit and a shiny AmEx card just for the occasion, hoping that this will be the time Trent finally lands on his feet. Trent can’t help but feel for her: he really intends to try, even arriving hours early to town the morning of the interview. He passes the time wandering by his grandfather’s old shoestore where he had spent countless hours repairing sneakers as a teenager. On this particular morning, he swallows the sadness—willing the visceral memories of a happier time to dissipate—and walks inside the old store, now a Starbucks. Within minutes, an employee catches him finishing off a miniature bottle in the storage room, and things only go downhill from there.

Bourne has a habit of pulling this trick repeatedly, willing readers to watch as Trent strives for goodness, and falls short. It forces one to recognize the futility of willing Trent to simply move forward. Even asTrent begins to lay off the alcohol, the universe does not miraculously deal him a better hand. Bourne successfully demonstrates how painful sobriety can really be for someone like Trent. For the first time, and all at once, Trent finds himself with no easy excuses and a whole lot of expectations: making rent, going on dates, and most urgently, staying sober.

It is in this latter half of the novel where Bourne’s skills shine as he expertly crafts Trent’s dizzying descent into chaos. As Trent’s outstanding problems pile up and his desperation grows, his newfound sobriety allows him to forge new connections with other locals. It is through these relationships, and the shining light Trent’s sobriety brings to the inner life of these secondary and tertiary characters, that Bourne demonstrates his talent. He has the ability to narrate a character’s deepest struggles and sincerest hopes with a clarity nearer to biography than fiction.

Bourne’s characters are thus rich with significance, exemplifying the themes that punctuate Trent’s central struggle and the more unifying one of Marinites attempting to fit into a place that may no longer include them. Bourne’s efforts to accurately depict the social and political realities of Mill Valley come from a loyalty to the landscape; this fidelity helps ground the imaginative fiction of the text. And yet, it is Trent’s inner world that feels glaringly realistic. Michael Bourne understands people, and perhaps most particularly, those living on the ragged edge of hope. In the last pages of the novel, Trent’s attempts to hold onto those he loves veer off the rails—no miracle comes to save him. All we are left with is the possibility of absolution, of solace for those Trent has hurt.