Q: “Which is the product, you or the book?”

JS: “Way back… the author, the successful author, sold himself, only we didn’t have the media. If you recall, Ernest Hemingway… there was always great publicity, how he was a great white hunter, how he went to the bullring… and so you sort of almost mixed the man with his character, they said, ‘That’s really Hemingway.’ F. Scott Fitzgerald, he and his wife, Zelda, lived the same kind of flamboyant life in the south of France as the kind of Americans they wrote about. And then along came television, and the shrinkage of our own American newspapers… Now what happened was that most authors were authors who wrote and they would get to television and they would say ‘Uh… ah… yes, ma’am, uh… yes,’ whereas, I was an actress before. So when I came on I felt perfectly at ease with the camera.”

–Jacqueline Susann, from a video interview with Elaine Grand, recorded in September 1973

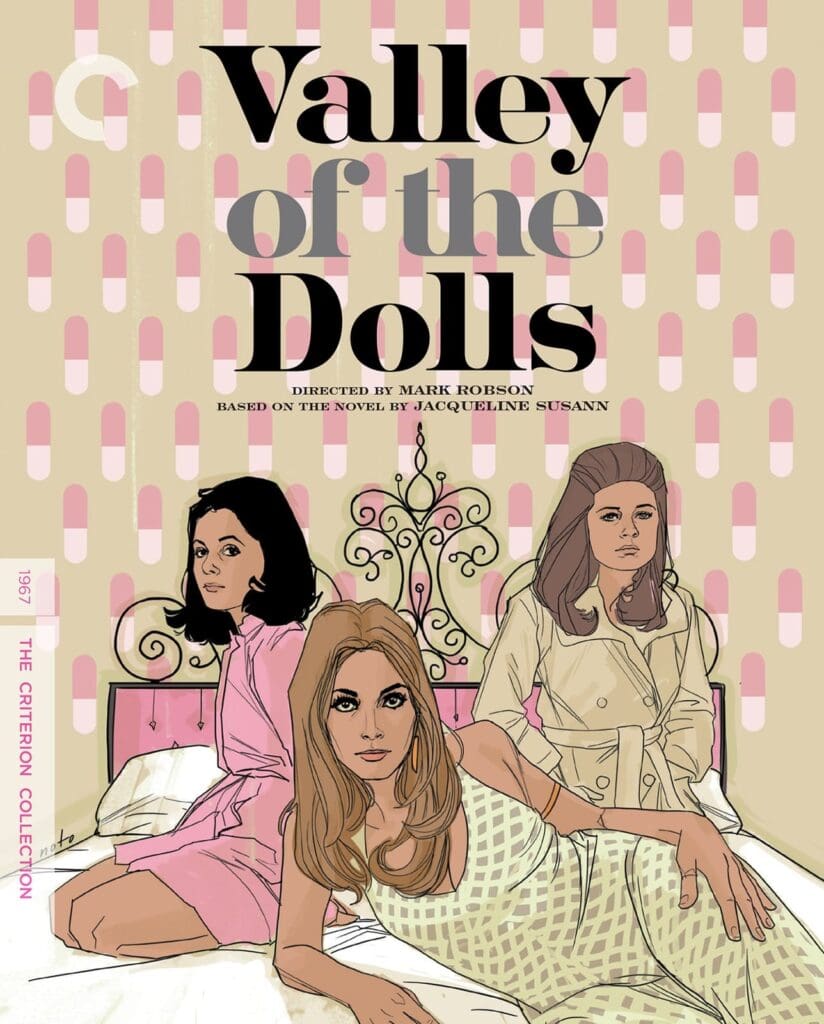

Near the end of Valley of the Dolls, the glamorous actress Jennifer North (Sharon Tate)—run through the Hollywood wringer, addicted to drugs, and, at thirty-seven, coming off a run of the European arthouse/softcore circuit—is diagnosed with breast cancer and can only be saved by a combination of mastectomy and x-ray treatments on her ovaries, the latter of which will render her infertile. At this, her lowest point, convinced by her mother and a series of poisonous men that she has little inner worth (“All I’ve ever had was a body, and now I won’t even have that”), she purposefully overdoses on sleeping pills, the “dolls” of the title.

The next morning, as Jennifer’s body is wheeled out of the Bel Air Carlton on a gurney, the media mobs the survivors, flash bulbs bursting and 16mm cameras whirring. The first reporter—quite fashion-forward in a zebra-trimmed, eggshell white Chanel suit and donning Jackie Susann’s signature ’60s bouffant—clutches her notepad and confronts Jennifer’s best friend, Anne Welles (Barbara Parkins), a famous model. “Miss Welles, you were the last one to see her alive…was she depressed?” She speaks in a measured, aristocratic, mid-Atlantic affect, halfway between Hedda Hopper and Katharine Hepburn. Other reporters begin shouting their questions, but the first reporter coolly follows up: “Then you think it was accidental?”

Anne, shell-shocked, stammers through her responses, unable to complete a sentence. “Could you give us her measurements?” shouts a male reporter, and Anne’s lover hurries her offscreen and out of the scene.

At first blush, this would appear to be a typical, “blink and you’ll miss it” author cameo, lacking in substance. It appears toward the end of the camp-addled Hollywood adaptation of Valley of the Dolls, a widely-derided film whose greatest legacy might actually be the Castro Theater’s Patty Duke gala, “Sparkle, Patty, Sparkle!” But for those who know Susann’s life and career well, her brief screen appearance is rife with eloquence and personal meaning.

Born in Philadelphia in the midst of the 1918 flu epidemic, Susann grew up idolizing the performers of vaudeville and the silver screen. At seventeen, she left for New York City, hoping to take Broadway by storm. After her big break, playing “First Model” in The Women (her billing in Valley of the Dolls as “First Reporter” is potentially in reference to this debut role), she spent a decade floating up and down the Great White Way, sometimes as a replacement, a chorus girl, or in a supporting role; frequently adjacent to the spotlight, but never fully in its glow. Frustrated by Broadway’s punishing and often unsavory treatment of aspiring starlets (which included, for Susann, a diet of Dexedrines and sleeping pills), she took to writing. Her first play, Lovely Me, ran for a mere thirty-seven performances on Broadway and was savaged by critics—an experience so apparently traumatizing, it moved her to punch one of the reviewers in the face, a full year afterward.

Susann shifted her focus to television, appearing in a mix of comedy, variety, and suspense programs throughout the late ’40s and early ’50s. For one month in 1951, she hosted her own TV show on the DuMont network (Jacqueline Susann’s Open Door), where she, like the First Reporter, pursued soft news, interviewing celebrities and tear-jerking human-interest subjects. Then, she fell into the world of advertising, and as she told The Saturday Evening Post in 1968, “I started on a terrible commercial called Schiffli’s Embroidery. It paid well, and it ran for five years, and then one night I came out of Sardi’s restaurant and a kid yelled, ‘There’s the Schiffli Girl!’ And I thought, fifteen years of trying to be a good actress—to be the Schiffli Girl? That’s when I decided, it’s put up or shut up, I’m going to write.”

She and her husband, Irving Mansfield, became tenacious self-promoters and pioneers of the modern book tour. Though her work often trafficked in prurience and gossip, her institutionalized son, drug use, and battle with cancer were well-kept secrets from her audience. She fine-tuned her persona for her (sometimes amphetamine-fueled) media appearances as “Jackie Susann, the Product”: at once a bestselling, high-society empress and a straight-talking, two-fisted demimonde. She was Flaubert, the Fitzgeralds, and Dorothy Parker all wrapped up together in Pucci and Chanel. With melodramatic trappings, her novels interrogated American culture, its obsession with fame, its underlying misogyny, its bourgeois drug abuse, its abusive prime movers. With Valley of the Dolls (1966), she took aim at every corruption she had witnessed throughout her career: in publishing, modeling, television, Broadway, and Hollywood.

Susann’s editor, Don Preston, told Barbara Seaman—birth control activist and Susann’s biographer—about Susann’s role in the film. “Her reaction was funny. She said, ‘But I’m a professional actress, and I’ve done lead roles. I don’t do bit parts.” Nevertheless, she appeared in the role, which, in less than thirty seconds of screen-time, manages to engage with an entire laundry list of Susann’s lifelong struggles and obsessions.

The sheer dimensionality of the cameo is impressive: the First Reporter, a version of Jackie the TV Personality, is questioning a more innocent version of Jackie the Aspirant/Jackie the Model, about the death of a Jackie who’s been chewed up by the fame-industrial complex, Jackie the Cancer Victim. This third dimension—the part of Jackie who was Jennifer North, and who may have even contemplated suicide before she decided to forge ahead with her treatments, was secret from the public. It cannot be coincidence that Susann’s “Hitchcock,” as she called it, appears in such close proximity to the episode of the story based on her greatest and most private test.

Susann attended the film’s premiere aboard the luxury ocean liner Princess Italia as part of a gimmicky, globe-trotting press junket. According to her husband, she watched it quietly, betraying no emotion, but cornered the director afterward, unloading her critique: “This picture is a piece of shit.” Susann disembarked early, in the Canary Islands, her disappointment plain. Regardless of its faithfulness to the book, the film was a financial smash. The Susann brand was a juggernaut.

It would be lung cancer, metastasized from the original breast cancer, that ultimately claimed Susann’s life in 1974. She published four books in her ten year race against death; two additional, posthumous works would follow. Her remains were cremated and laid to rest in a bronze, book-shaped urn. Her husband placed it on the shelf, alongside the rest of her work.

Sean Gill is a writer and filmmaker who won Michigan Quarterly Review‘s 2020 Lawrence Prize, Pleiades’ 2019 Gail B. Crump Prize, and The Cincinnati Review’s 2018 Robert and Adele Schiff Award. He has studied with Werner Herzog, video edited for Netflix’s Queer Eye, and was directed by Martin Scorsese (on HBO’s Vinyl). Other recent writing has been published in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Threepenny Review, and at Epiphany, where he writes the “Lurid Esoterica” column.