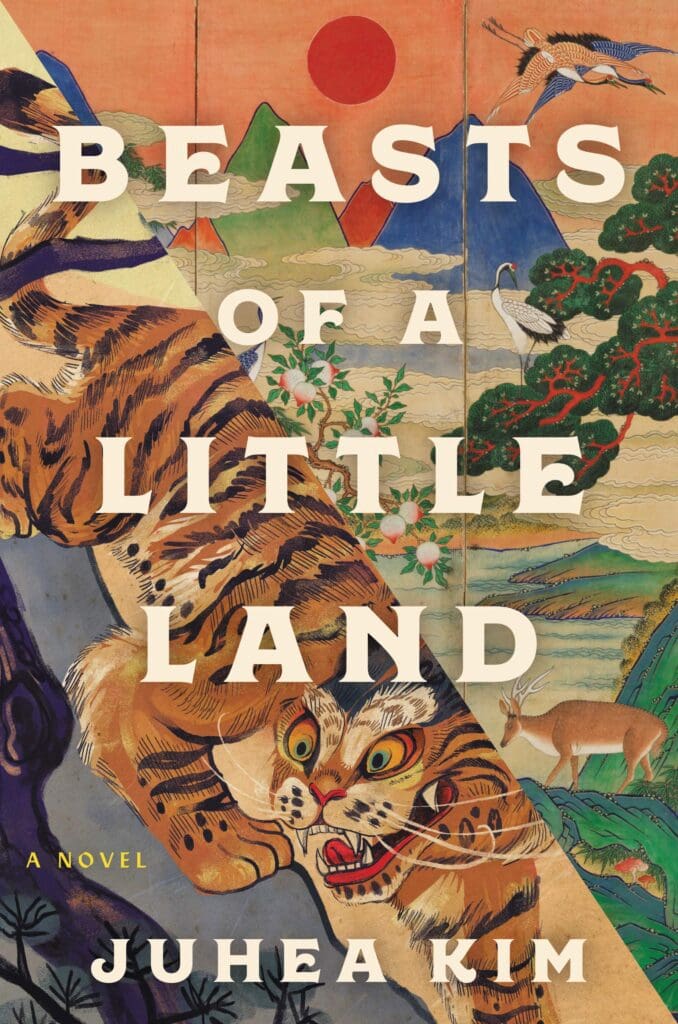

Juhea Kim’s first novel, Beasts of a Little Land (416 pages; Ecco), is an epic tale of occupied Korea that spans nearly five decades. Beginning in 1971, the highly ambitious narrative delves into Korean history and mythology and grapples with the dilemma of seeking meaning in a perilous world. Kim was born in Incheon, Korea , and moved to Portland, Oregon, when she was nine. She is a climate advocate, and her story “Biodome” appeared in ZYZZYVA Issue 120. She recently spoke to ZYZZYVA over Zoom about her new novel, writing compassionately, and suffering for love. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

ZYZZYVA: Beasts of a Little Land covers a lot of territory. It has beautiful mythology, but it is also a political novel and a love story. There is a resonant line in the book about how love is measured by how much suffering a person is willing to go through for another person, and that seemed like a major theme of the book. What drew you to writing this type of unrequited love story?

Juhea Kim: When I first sat down with this task of writing a novel—and I wrote a novel because my agent said stop writing short stories and write a novel—I was like, Okay [laughs]. But I knew that it had to be in this time period and in this setting, because it is actually very close to me. It’s inspired by my maternal grandfather, so I knew that it was something that I could be obsessed with for years in an authentic way. I also knew it was going to be a love story between three people. I just always had this feeling. I knew that there was going be a woman in the center, and a man that she loves more than he loves her, and a man who loves her more than she loves him. That always creates conflict—in life as well as in literature. It’s very rare that you meet someone and you love each other mutually and equally. I think that’s the ideal, but in real life someone’s going to love you more or you’re going to love them more, even if just by a little spoonful, and that creates an imbalance. That kind of tension was very interesting to me, and from that came the story of JungHo, Jade, and HanChol.

Z: It is a traditional love triangle in that sense, but it also felt like the characters all yearn for something bigger than the love of another person. They all seem to desire love, but also some type of societal recognition.

JK: They’re all yearning for something larger and kind of just missing the target. I think that’s true to life. How often in life do we think that we want love, or we think that we are in love, but then we’re thinking about different things even while lying next to this person in bed?

Z: There’s a character, Ito, who is a Japanese officer in occupied Korea, and during a peaceful protest he severs a protestor’s arms and then stabs him in the back. The book is filled with many moments of extreme violence like this, and Ito’s often a perpetrator, yet you write him so compassionately. At one point he gives Jade some of the most important wisdom she receives.

JK: He says, “You place too much importance on other people,” and then also: don’t care about other people. Don’t trust anyone. Just stay alive. It’s very cold, but also truthful. He’s giving the best wisdom he can give her, his own philosophy. That’s a real form of intimacy and connection from a character who’s clearly a villain.

Z: But he also serves a really important function as this counter to all of the other characters. How did you feel about writing him?

JK: Ito was one of my two favorite characters to write—the other being SungSoo—and they’re both antagonistic characters. I focused a lot on creating villainous characters with compassion. I wanted them to feel like real people and I gave them a lot of pieces of my own soul. What you see in Ito or SungSoo that’s even a little bit relatable or even endearing or compelling, that’s probably the pieces of me that you see. There is a karmic balance to Ito. I was concerned about that [violent protest scene] and my editor asked, isn’t that a bit much? But I really pushed for it because that was a scene I had read in history books and that really struck me. The fact that someone had his arm cut off by a sword while carrying the flag, and then kept running, and then got his other arm cut off, and then died, that stuck in my memory. Those types of portrayals are not exaggerated, and it was important to me to be true to history, but also to give a sense that these people in history who perpetrated these violent crimes possibly also had humane sides.

Z: You write from many different perspectives in this novel. Two of the main protagonists are a courtesan and an orphan. What compelled you to focus on these people in the fringe of society as the containers for this story?

JK: My maternal grandfather very roughly inspired the character of JungHo. By that I mean that there’s nothing about his personality, romantic story, or character traits that directly correspond to my maternal grandfather; however, my maternal grandfather was born during the colonial period, and he passed away before I met him. All I had to know him were a very few photographs and the stories that my mom has told me about him. What I do know about him is that he was pulled out of school around 10, so he didn’t get a whole lot of formal schooling, and he made his living as a hard laborer. He was a bricklayer and he did a little bit of subsistence farming as well. He told his children one thing that really stood out in my mom’s memory: that he was driving in Shanghai and that the roads in Shanghai were paved and divided by bronze rivets. He was also, very oddly, an amazing tennis player. As I was doing research for this novel, I read that resistance fighters living in Shanghai were under so much stress because they had to be on their feet all the time in case of an attack, so in order to relieve stress, they did a lot of recreational activities, including tennis. When I saw the word tennis, I was like, Oh my God, grandpa. It felt so affirmative—this character who’s from the fringe of society could unwittingly get caught up in the grand sweep of history.

As for Jade, I knew that there was going to be some backlash for my choosing a courtesan. An Asian author writing about Asian courtesans immediately downgrades the work to a kind of unctuous Asian historical fiction. It’s not literary fiction—it’s considered “Asian historical fiction,” and maybe for women’s book clubs. I was defiant of that because that’s also a form of racism. You see, La Traviata by Verdi is inspired by a real-life 19th century French courtesan named Marie Duplessis. La Traviata is considered one of the most canonical works of Western art, in one of the highest art forms such as opera, ballet, literature, and cinema. Nobody is saying that’s historical fiction or somehow less worthy of the highest literary forms. Everybody thinks that those are masterpieces. But if you’re talking about the Asian courtesans, it is somehow lascivious. It’s not. Courtesans were actually such an important part of Korean culture going back centuries. They were highly educated, they had to be extremely accomplished in order to even communicate with the gentry that they entertained, and they communicated in such poetic forms. They were expected to compose spontaneous poetry or create paintings full of symbolism on the spot, so they had to be extremely smart. In fact, their primary charms were not just their looks, it was really their brains. They also played such an important role in the independence movement. So, it made sense to me that courtesans, with their rich history and their cultural accomplishments and relative freedom as women during that time, would allow for a better plot and more interesting characters.

Z: There’s a line in Beasts of a Little Land from the character of MyungBo’s experience that really struck me. It reads:

“At a time like this, an apocalyptic time if ever it was—his people dying under the Japanese bayonet, everywhere in the world bloodshed and rape, and war in Europe, which only just ended—people still thought about going to university, obtaining a lucrative post, or squeezing more profits out of their land, and churning ever greater wealth as if the world itself weren’t burning all around them.”

As an artist in California, where sometimes the world is literally burning, I couldn’t help but see the connection to climate change and the ways we still desire to make something beautiful as artists or even just excel at work and continue with business as usual. How do you think we reconcile that desire to create or to exist in the world while also suspecting it might not matter or that it might be futile?

JK: I’m so glad that you picked up on that line. That line is really the cri de coeur of this book. It’s something that I, as an artist, think about, and that I grieve. I always wanted readers to understand that this is meant to be speaking to us now. It’s not just a history lesson. I really struggle with the sense the world is slipping away, yet I still need to continue to work and live my meager personal life. The other option is just giving up. MyungBo’s solution to this problem is to throw himself completely into it. He gives up his wealth. He becomes this head revolutionary, privately funding and organizing. Through that he finds meaning in continuing to live in this type of world. For me, I also choose that kind of path, though mine is far less dangerous on a physical level.

When I was in my late 20s, I felt like I just didn’t know where I was going with my life. I had worked for a New York publisher for some years and quit that job. I was running fast out of the savings I had made from being an editorial assistant, and I wasn’t being published at all. I didn’t know whether I should give up. The reason I didn’t is that I came up with a mission statement. I did some soul searching and I thought, my mission is to use my talent for writing to save nature and reduce animal suffering. Once I found that, I thought, Oh my God, I’m gonna get rejected so much, but I still have a reason to get up in the morning and start writing again. Whether it’s a small article or a novel, it’s all going to serve the same purpose. I didn’t write this book to see my name on the cover of a book and to feel fancy about myself. Ultimately, my personal life is quite meaningless, especially given the fact that we are in such an imperiled state; however, if I know why I’m doing this, why I’m getting rejected, or why I’m unhappy with this type of artist’s path, I can still feel so lucky and privileged to know I am moving the needle just a little bit forward each day.

Z: I love the idea of distilling it down to one thing.

JK: I think one sentence is the key because it’s so simple you can’t lose a sense of it. It’s also a great way for me to know which project I should be focused on. I write everything besides poetry, and it all has that through line. You can get a sense of that reverence for nature in Beasts, not only because of my personal advocacy, but because that is the foundation of Korean culture. Koreans really view nature as our kin, especially the tiger. The tiger is an animal whose significance to Korean culture and history cannot be overstated. If you read Korean folklore, the tiger is such a multi-faceted creature. It’s stupid; it’s brilliant; it’s cunning; it’s noble; it’s merciful; it’s vengeful. It is all those things. It’s mindboggling that we were able to coexist for 5,000 years side by side without the tiger going extinct because of this sense of harmonious living with nature. This book is really steeped in that philosophy as well as my personal advocacy. I am donating five percent of my author proceeds to the Phoenix Fund, which is a tiger and leopard conservation nonprofit based in Vladivostok, Russia.

Z: I’m glad that you bring up the tiger in Korean folklore. I found the moments in the novel where realism slips into mythology and shapes the characters’ identities and worldviews to be compelling. Was there a story from your childhood or a myth you grew up hearing that shaped you as a person?

JK: I don’t know if there is just one because I was such a bookworm and read all of the folklores, myths, and history books about Korea. I moved here when I was nine, but even when I was younger than that I was reading these medieval history books about Korea during the Three Kingdoms period. These history books had actual events, but were also full of mythology. One of the running themes of Korean mythology and legends is metamorphosis. There are a lot of animals turning into humans and humans turning into animals. I think that writing Beasts of a Little Land was only possible because of all the stories that I grew up reading which made me realize we are all connected with nature.

SH: Can you talk a little about your writing process?

JK: Beasts is a highly plotted book, but I didn’t outline so much as instinctively know where things were going to fit. I often have a very abstract image in terms of how to structure my book. This one I modeled after Bruckner’s Symphony No.8, which is a majestic symphony. It goes through torments and lapses in faith only to arrive at a sense of redemption, and I wanted to capture that sense of going through turbulence to arrive at grace. The symphony is structured like a cathedral. Cathedrals aren’t built from the façade in but from all four walls. So at first you don’t know what it’s going to look like. It looks just like a bunch of stones, but you must know from the very beginning where the keystone will fit. With that image in mind, I knew where the keystone would be, how the story would end, and so I was sprinting toward that.

I think whether I am writing a short story or a novel I am really driving towards that final emotion. Who I most identify with is the Korean novelist and critic Yi Mun-yol, who said that “The greatest value literature can have is poignancy.” That’s a very Korean way of looking at it and it’s very different than American literature, at least what’s in vogue right now. I don’t think poignancy is given a lot of priority by contemporary American writers. You need to move people, and you can’t move people unless you hurt them. You have to break their hearts. I think empathy is only possible if your heart is broken. It’s the way literature can save people and save the world.