1996

Irvine Welsh is “Mikey Forrester”

“I’m playing this drug dealer who’s probably one of the most unsympathetic characters in the book, cause, probably kinda manipulative and nasty and sort of horrible guy so, a lot of people will be saying sort of type-casting again, you know?”

—Irvine Welsh, in a video interview from the set of Trainspotting in June 1995

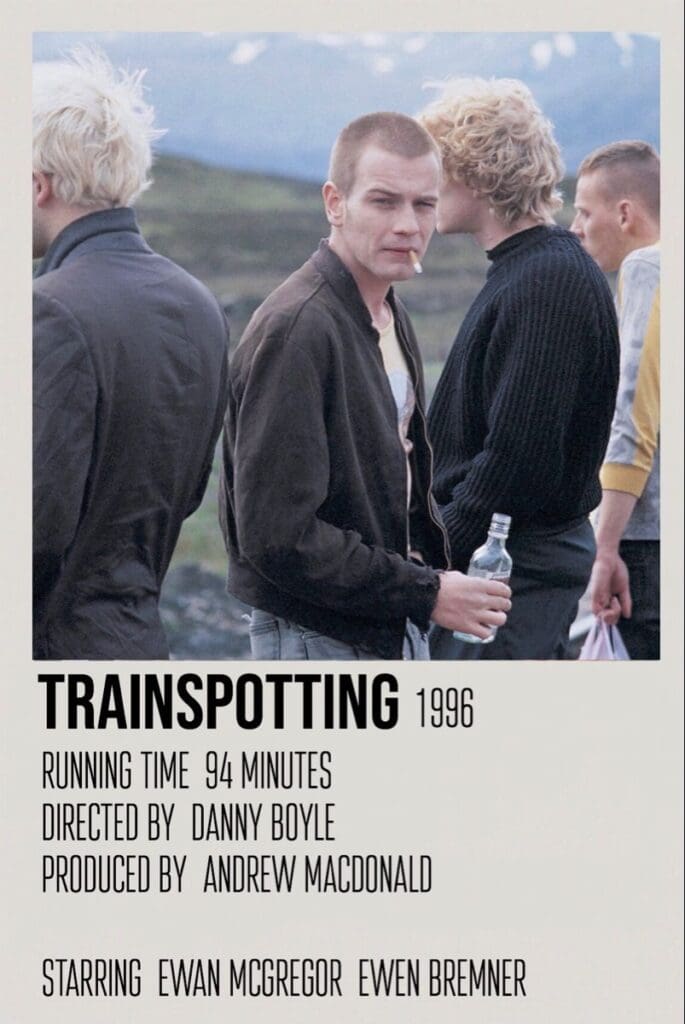

To the strains of Bizet’s Carmen, Renton (Ewan McGregor), a young Edinburger junkie, makes fastidious personal preparations for kicking heroin, the final step of which is obtaining one last hit from his dealer, Mikey Forrester. Mikey appears, smirking like a lunatic in a punk t-shirt, knee-ripped jeans, and a sheepskin jacket, looking nearly exactly as Welsh describes him in the novel (“…beefy-faced but thin-bodied, almost bald at twenty-five. His hair loss over the past two years has been phenomenal, and ah wonder if he’s goat the virus. Doubt it somehow. They say only the good die young”). Mikey is furnishing Renton with two opium suppositories, which he describes methodically as “slow release, bring you down gradually, custom designed for your needs.”

As Renton is contemplating the suppositories, Mikey reclines on a dirty mattress, plucks a used cigarette butt from his ashtray, and carries on, grinning like the Cheshire cat. He observes with a disconnected, sadistic curiosity as Renton reaches into his trousers, inserts the suppositories, and presses them home. “Are you feeling better now, then, eh?” he asks. Renton replies, “Oh, aye, for all the good they’ve done me, I might as well have stuck them up my arse.” This leads directly to the infamous Worst Toilet in Scotland setpiece: a bout of diarrhea, submersion, and repulsive rebirth which is perhaps the most viscerally memorable episode in the story.

Mikey resurfaces, too, late in the film’s third act. Renton has since relapsed, participated in the death of an infant (through neglect), been arrested for shoplifting, undergone a painful rehabbing, and begun a meaningless yuppie existence on the straight and narrows as a realtor. Reconnecting with his old skag friends after a funeral, Renton becomes reluctantly involved in a heroin deal, with Mikey once again acting as a catalyst. Mikey is described as having accidentally/drunkenly bought two kilos from Russian sailors (and we cut away to him, saucer-eyed, awakening in a cold sweat, realizing what he’s done). Later, when a sober Renton is pressured to assess the heroin’s quality, a bumptious Mikey is standing alongside Renton’s friends, anticipating his reaction with all the compassion of a schoolyard bully watching an ant trapped under glass. Renton shoots up, ending his sobriety, and declares the drug’s quality to be superior. Mikey offers a smug thumbs-up with decidedly cretinous enthusiasm.

Irvine Welsh himself had, in turns, been a juvenile delinquent, a burgeoning punk musician, and a heroin addict (the habit lasted around eighteen months, and he ultimately kicked it, cold turkey). Before he wrote Trainspotting (1993), he had turned over a new leaf and reinvented himself as a realtor, a house-flipper, and a local bureaucrat in pursuit of an MBA. Welsh lived both sides of this coin so specifically that Renton strikes the reader as plainly autobiographical, and, indeed, as Welsh notes in a 2018 Guardian interview, “Renton is in some ways a more authentic self. I write more self-consciously when I write as him.”

If Renton is Welsh’s true alter-ego, Mikey Forrester is one of his great tormentors, the man who supplies him with the junk that poisons his body and jumbles his soul.

Mikey is there when Renton quits, actively making it worse. He’s there during one of Renton’s relapses, also making it worse. He dwarfs the simple joys in Renton’s life (music, namely) and takes on a nearly mythical dimension. In the novel, Renton professes, “Ah’ve goat every album Bowie ever made. The fuckin lot. Tons ay fuckin bootlegs n aw. Ah dinnae gie a fuck aboot him or his music. Ah only care aboot Mike Forrester, an ugly talentless cunt whae has made no albums. Zero singles. But Mikey baby is the man of the moment… The moment is me, sick, and Mikey, healer.” To see Welsh as Mikey on film, performing casual sadism and general amusement in the face of Renton’s afflictions begins to feel like a literalization of the koan-ish observation, “you are the cause of your own suffering.”

The musical angle, too, is a revealing one. In the late 1970s, Welsh played guitar and sang for London punk bands like The Pubic Lice and Stairway 13. The highs and lows of his eclectic biography—from heroin to the Hackney Council—led him away from music. In his post-Trainspotting fame, however, he defied his inner Mikey and began DJ-ing and cutting acid-house techno tracks. By the fifth novel in the Trainspotting series, Dead Men’s Trousers (2018), Renton has become a successful DJ, his career’s wide-ranging oscillations continuing to mirror those of his creator.

Welsh’s initial rise to fame was a whirlwind—the episodic, disorienting, and dialect-driven Trainspotting began as a cult novel and emerged a bestseller. Three years after publication, the film adaptation was completed (largely financed by Channel 4), released on the festival circuit, and beloved at Cannes. It was distributed in America by the Weinstein brothers’ Miramax Pictures (where it was marketed as a sort of Scottish Pulp Fiction), and its writing was nominated for an Oscar. When Welsh appears onscreen as Mikey Forrester, he wears a t-shirt, silk-screened with the image of the mohawk-sporting Wattie Buchnan of the Scottish punk band The Exploited. Perhaps Welsh is showing off his street cred, his local pride in Edinburgh’s punk scene. Or perhaps “The Exploited” is a subtle message about the film industry, an expressed fear about what could come from all of these separate forces, rising beyond his control.

To this day, Welsh makes jokes on Twitter about his acting career. After Danny Boyle quit the latest James Bond film, No Time to Die (2021), Welsh tweeted, “He resigned because the studio refused to cast me as the new Bond, arguing that I was too ‘strongly identified with the iconic Mikey Forrester character from Trainspotting.’ Danny thought I had the dramatic range and held out for me—a true friend.” He reprised the role of Mikey in the sequel T2 Trainspotting (2017), where he has become ever-so-slightly more respectable, having graduated from heroin dealing to fencing stolen goods. “Mikey Forrester has gone up in the world!” Welsh tweeted.