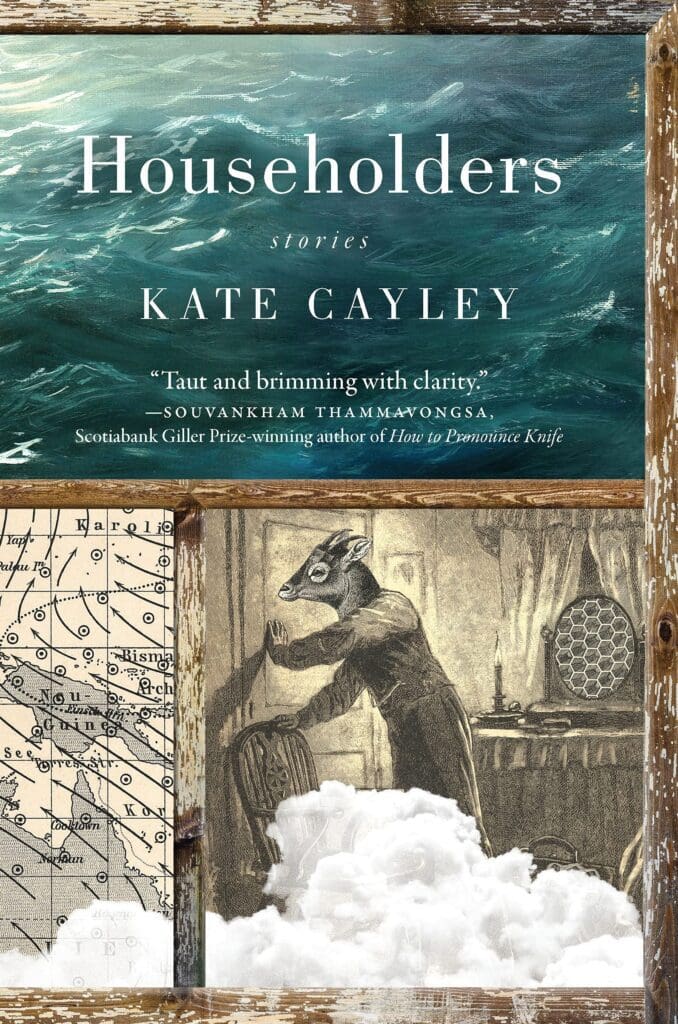

In a 2013 interview, Canadian writer and theatre director Kate Cayley noted the influence of Wendell Berry’s poetry on her writing, describing him as “a voice crying in the wilderness.” It’s an apt description of Berry’s work, suffused as it is with a sense of the bucolic and the simple in the face of the anthropocene and capitalism. Yet, in a very different sense, it’s also an apt description of Cayley’s stories in Householders (224; Biblioasis), her most recent story collection. Even surrounded by others, Cayley’s characters in Householders are often alone—misfits, runaways, forsaking the ties of friends and family, blogging into the void of the Internet. These characters are searchers and yearners, each pining to be a part of something greater and to define their purpose in the face of isolation.

In “The Other Kingdom,” Cayley introduces Naomi and Carol, two college-aged friends stalled in rural Maine on the tail end of a road trip through the United States, debating if they should continue roughing it or return across the border to their homes in Toronto. Cayley writes that Naomi had come to America “hoping to find a new life,” and that “she wants to read everything, and have everything connect to everything else, all tending to a single point of incandescence.” Naomi joins a commune, living for ten years and birthing a child in a farmhouse in Maine. Carol splits, returns to Toronto and to the semblance of a respectable life, forever questioning her decision to leave Naomi behind.

“The Other Kingdom” is the first thread weaving together the themes and narratives of Householders. Each of the collection’s nine stories at least references the commune or its inhabitants in passing, and five of the stories directly document snatches of Naomi’s life and those of her daughter and granddaughter, tracing the impact of Naomi’s decision to join the commune, and tracing their family lineage all the way through a near-future apocalypse. Cayley plays loose with time, sequencing the story of Naomi and her family out of chronological order. This, and Cayley’s techniques, give a sense of elastic time. The narrative jumps days, weeks, even decades within and between stories, even in sentences such as this: “John puts his hand on her still-flat belly and tells her that the baby is a girl. Later, she tells her daughter this story, and still later, she lifts her into a car as she sleeps and leaves in the middle of the night.” These proleptic moments occur frequently in the collection, emphasizing the multigenerational context in which many of these stories play out.

The relationship between Naomi and Carol in “The Other Kingdom” is also archetypical of many of the relationships throughout. Often, Cayley’s stories bring together one character who has chosen life on the margins of respectable society with one who pursues pragmatism. The divide between each ratchets a quiet but palpable tension. Nowhere is this more evident than in “The Crooked Man,” the opening story of Householders.

The story follows Martha, a mother described as having too many children and being “disordered and apologetic.” Martha is juxtaposed with Bronwyn, another mother whose son, Max, is the same age as Martha’s son, Noah. Where Martha is frazzled, Bronwyn is poised; where Noah is a loner and prone to rage, Max goes to birthday parties with his classmates. The mothers’ interactions, written mainly through dialogue, are excellent. In one particularly strong passage, they discuss plans for a street party:

“You shouldn’t worry so much. You have so much to worry about. If you’d rather not run the craft table—”

“No, no—”

“Maybe that would be better anyway. You have so much on your plate.”

“It’s fine.”

Martha sounded angry again. She didn’t know how to stop.

“I do wonder if it would be better. For the whole thing. If we didn’t have it. I’ve been thinking. Maybe better to skip it? It’s such a generous offer, but those things can be so messy.”

“I don’t mind.”

“I think it might be a better choice not to have a craft table. Maybe next year. When you’re less overstretched.”

Martha and Bronwyn are polite, conversational, but Cayley perfectly captures Bronwyn’s patronizing tone and the passive aggressiveness undergirding the conversation. The pair’s restrained tension is contrasted with the shock of violence flaring up at unexpected moments in the story: Noah, arguing with his father, intentionally banging his head against the exposed brick of the chimney; the appearance and reappearance of an unnamed, angular and unnatural seeming man on a bike, flashing through traffic, a vision for Martha of who her son might become. With each turn of the page, there is the foreboding dread that something will snap, that eventually the small violences cutting into Martha and Noah will bleed them dry.

“The Crooked Man” is compelling not only for its ominous depiction of middle-class life fraying at the seams, but also for its display of Cayley’s poetic style. Throughout the collection, her writing is often descriptive and lyrical, accentuating by contrast the infrequent passages where she tends toward staccato, propulsive sentences. “Doc” and “Pilgrims,” in particular, are full of startling turns of phrase and evocative descriptions. The emptiness of a trailer is described as a “cold ooze,” and a character’s voice is “like a man who’d spent the night crying and then driven a nail into his thumb.” In these instances, Cayley’s background as a poet—she has published two collections of poetry—shines.

Before transitioning to poetry and then to short stories, Cayley worked as a theater director and as a playwright. Householders feels like a summation of those experiences. There are the tight narrative structures, learned from a previous story collection; a poet’s expressive, vivid voice; and the lived-in dialogue, honed from a decade of playwriting. With Householders, Cayley has envisioned a world that mirrors our own like a distorted funhouse—a place where the moral and physical stakes are heightened, where emotional bonds run deeply, and where something menacing is often lurking. It’s a frightening world, but it makes for a compelling story collection, as good to tear through for the narrative as it is to savor (and savor again) for the language.