When I applied to the Community of Writers Poetry Workshop in 1987, I had no idea what I was letting myself in for, or that this unique summer program would become my poetry home. I had just read The Gold Cell, and saw an ad in Poetry Flash that mentioned Sharon Olds was teaching at the workshop. I blush to say that I’d never heard of Galway Kinnell or Robert Hass at that period of my life; with four children and full-time work, I was out of touch with the world of poetry.

When I arrived in Olympic Valley that first Saturday, stowed my portable typewriter on a desk in my shared room, and went down to dinner, I was met by the imposing Galway, who announced we were each going to write a poem that evening and turn it in by 7:30 in the morning, and that we’d be doing this every day for a week. To say I was startled would be an understatement. I saw my consternation reflected in the faces of the thirty-odd poets around me. We went to dinner, and no one had trouble talking to the strangers sitting next to them; as an icebreaker, Kinnell’s announcement was a huge success.

From that first day, when I found that the locked gates to my poetic self could spring open, I have been amazed and grateful for this unique gathering in the high elevation of the Sierras, where poets at various stages of their careers come to test themselves against the task of writing fresh work to read the next day to strangers and (in many cases) to their poetry idols.

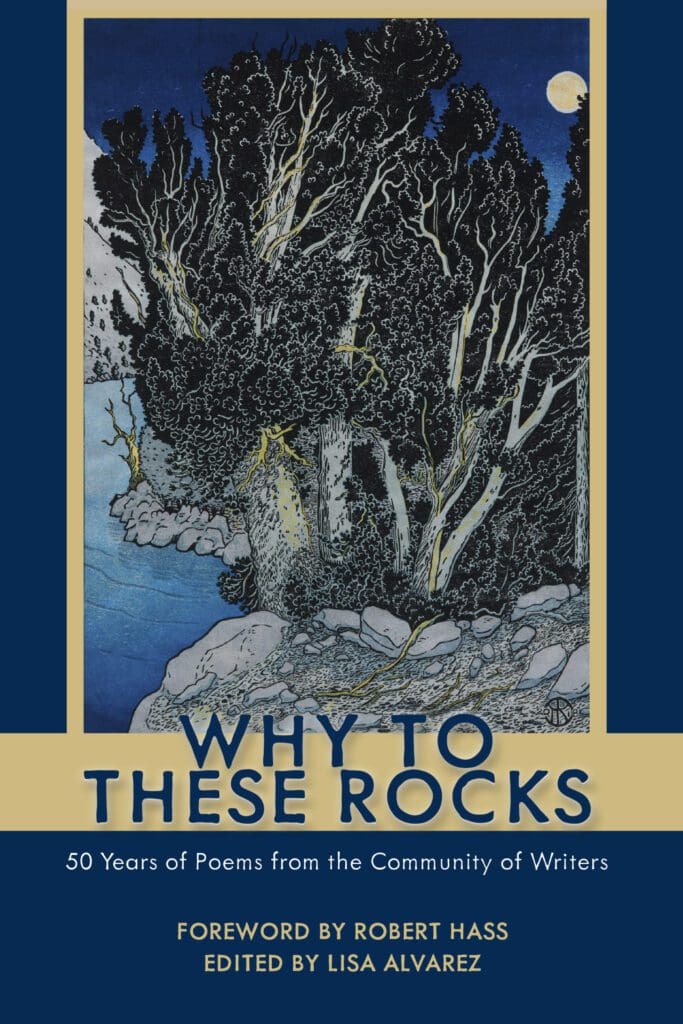

Why to These Rocks: Fifty Years of Poems from the Community of Writers, to be published by Heyday Books in April, presents a sample of the work produced by the workshop participants over the decades, and includes poems from an array of staff poets: Kazim Ali, Don Mee Choi, Lucille Clifton, Toi Derricotte, Rita Dove, Cornelius Eady, Juan Felipe Herrera, Brenda Hillman, Cathy Park Hong, Forrest Gander, Major Jackson, Yusef Komunyakaa, Harryette Mullen, Sharon Olds, Evie Shockley, C.D. Wright, Al Young, Kevin Young, Matthew Zapruder. It also features a never-before-published poem by Kinnell.

In helping to compile the anthology, I sat down with Robert Hass, Hillman, and Olds to better learn about this particular gathering that has flourished over the years, nurturing so many poets.

Along with the late Kinnell, Hass, Hillman, and Olds taught at the Community of Writers poetry workshop since the beginning of its life as a generative event. (Kinnell was the director of the workshop from 1985, for almost twenty years.)

Olds remembers meeting Kinnell in 1986. “I didn’t realize it at the time,” she said, “but he was sort of interviewing me to see if he wanted to teach a summer workshop with me. He wanted, I think, to hear my voice, to see if he would want to be holed up with me teaching for a week or two.” They wound up teaching together at a summer workshop on the East Coast. Most people brought existing work to discuss, but interestingly, the best poem that summer was one written at the workshop.

Hass had had a similar experience at a poetry workshop. Somebody showed him a poem and Hass commented, “I think the ending is not as strong as the rest of the poem.” The poet responded, “Well, Richard Hugo loved it!” Hass thought, “Dick Hugo has been dead for five years. People should not be workshopping poems for years that have been seen and worked on over and over.”

The following summer, Kinnell asked both Olds and Hass to teach with him at the Community of Writers. Kinnell told them he wanted to do workshops with only new work. This basic idea, that each participant, including the staff poets, should write a fresh poem each day, began in 1987, and according to Hass, by ‘88 or ’89, the workshop’s format was pretty much defined. Everyone arrives on Saturday and live in groups in houses around the valley. All participants (including the staff poets) that night write a new poem for Sunday morning, which volunteers collect early the following day. These are copied and distributed before the 12-person morning workshop. Then the cycle repeats.

“Craft talk on Sunday night, craft talk on Monday, we have to write a new poem each day. Then on Wednesday afternoon some play softball, others take the wildflower walk. Wednesday night, there’s the picnic at Lake Tahoe. As to the magic, everything contributes—the range of the craft talks, the activities, the place itself, and living and working closely together,” Hass said. “At some point, we introduced the optional morning walk guided by naturalist David Lukas. This leads to lots of poems with titles like ‘Aphids Herding Ants on a Mule Ear Leaf,’ or that muse about the Jeffrey Pine or the ant lion.”

The expectation of fresh work pushes the poets to work through exhaustion and find their way to the poems they were meant to write. Of course, sometimes participants and staff have a hard time with the process. Hillman described her initial response: “At first, I said to Galway, ‘This method doesn’t work for me. I have to listen in for my first line, and it has to marinate and if I don’t feel it’s a really musical sound it throws me way off, I can’t do this, I’m driven crazy by it, and I’m just going to use old poems.’ And he said, ‘Just keep trying.’ Over time, I realized if I get one thing from the week, one draft or two or three ideas, it’s worth it, and I can write three or four terrible poems and it’s okay.”

While it’s impossible for staff to be fully “equal” to the participants, the format is democratizing. Participants see rough drafts that demonstrate that their mentors start just as they do, with something awkward and unfinished, a poem that reaches for something it hasn’t yet achieved. It’s reassuring that the staff poets are not immune to the trauma of drafts that don’t make it.

Early on, Hass proposed, “No micro-editing. These are rough drafts, let’s see if we can locate the energy.” Dean Young famously called this method a “petting zoo,” but once you locate what is working in a poem, the poet is pointed in the right direction. By inference, poets sense what isn’t working. In this environment, everyone’s work improves over the week.

Each of the staff poets runs their morning session a little differently. In Olds’ workshop, you hear each poem first by ear before reading them on paper. Kinnell would appoint one poet to jump in right away and say something positive. The morning sessions are two hours, and there are a lot of poems to get through. Some leaders have the poem read twice, once by the poet, once by someone else. Lucille Clifton was one of the most deft editors I ever experienced. She had the gift of knowing which line or lines to shift to make a poem shine. Still, her interventions were few and only at the request of the poet.

Because the work produced in workshop is confidential and criticism is discouraged, staff and participants alike feel free to try new things. In the early ‘90s, Hillman started to write things at Community of Writers she wouldn’t try anywhere else. “It didn’t matter if it wasn’t the Brenda method,” she said, “it will produce the new Brenda poem.”

If you were to read Why to These Rocks, the unique spirit of the workshop that gave life to those poems comes through. Their power is attributable to what Hillman believes is “the secret” to Community of Writers— “being among people that allow you to access a power in yourself that you didn’t know you have. It’s very primitive, it’s very much what we needed from and didn’t necessarily get from our beloved parents. The powers of invention that we can share that make something happen in that process, partly under duress. Because you’re so tired, you don’t think you’re going to get another poem, but you do.”