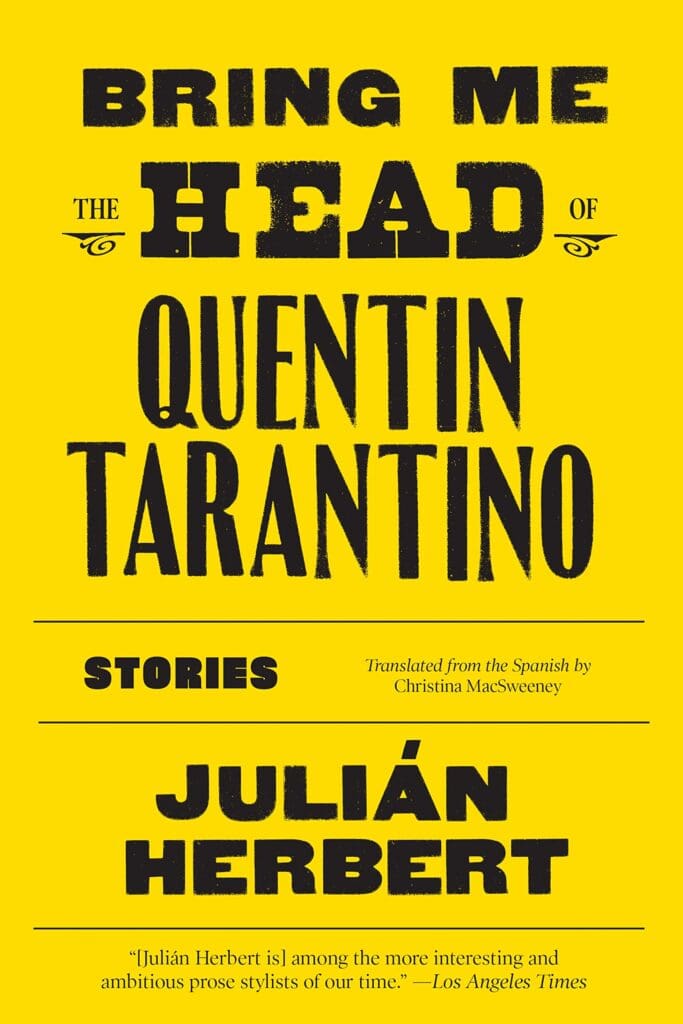

It’s no surprise that Julián Herbert’s story collection, Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino (167 pages; Graywolf Press), features a cast of questionable characters, gory violence, and punchy dialogue—all are hallmarks of the eponymous screenwriter’s films. Within the collection, the profane becomes sacred and the sacred is made profane: a Mexican official throws up on Mother Teresa, a photographer films “gonzo-porno-AIDS movies,” and a journalism professor masquerades as author M. L. Estefania. As diverse as the lives and professions of these characters are, they are all Mexican men who are seeking a better life by traveling outside the bounds of the law; yet thanks to Herbert’s biting commentary and narrative experimentation, each story feels unique.

Herbert’s characters often pursue a life of crime and yet, as deplorable as that choice might be, their actions are portrayed as a result of governmental and social failures rather than any moral deficiency. It is darkly ironic then that these men ultimately become the target of government forces. Who is the corrupted and who does the corrupting is one of the central questions of the collection. “Anything that still functions here relies on corrupting everything else,” says the title character in “Z.” He lives in a world populated by humans and zombies alike, and phones his zombie-psychiatrist once a week, constantly goading him into meeting in person, thus tempting the undead professional with harming the human patient he has sworn to help.

What stands out in the book is the importance Herbert places on stories themselves. By nesting stories within one another in a Scheherazade-like technique, he tackles the tradition of storytelling as well as its influence on the world. These are stories about storytellers—told by storytellers.

Though Herbert’s experimentation is not alway successful (“Caries” is particularly frustrating because of the pages of sheet music that crowd out the plot), many of the stories here baffle with their ingenuity. The title story, for example, is part essay and part parody, focusing on the similarities between Shakespeare and Tarantino, as well as the inevitability of influence. The subject matter lends itself perfectly to the parody woven throughout it, and while the story appears unique at first glance—a narco doppelgänger of Quentin Tarantino kidnaps a movie critic and sends his goons out to kill the director—it soon becomes apparent that it follows the same beats as many other stories about narcos and gangsters. One wonders if Herbert is suggesting that everything is a pastiche now, the only difference being how obvious one’s influences are. Art imitates life in a ceaseless feedback loop, which is perhaps why these stories so closely resemble one another, and why the first sentence of the collection is repeated at the end in a slightly altered form: “Stop kidding yourself: that thing you call the ‘human experience’ is just a massacre of onion layers.”