By the late ’80s in America, the term “heavy metal” conjured the image of bands who were as well known for their big hair and backstage antics as their music. It’s little wonder then that the Norwegian “black metal” scene felt like something new, with its shrieking vocals and monolithic riffs, and restoring some of the danger associated with the genre ever since Black Sabbath released their debut LP in 1970. The dark and sadistic imagery many of these bands conjured on their albums (sample song titles: “Necrolust” and “Deathcrush”) wasn’t simply for show, however, and by the late ’90s the genre became tarnished by a rash of church arsons attributed to musicians within its ranks, as well as some of its members’ involvement with the neo-Nazi movement. The tension among these bands culminated in the brutal murder of influential guitarist Øystein Aarseth, also known as Euronymous, forever casting a dark pall over the once fan-championed music scene. If the genre was founded and ultimately tainted by a collective of angry young men with untenable beliefs and violent tendencies, then the latest novel by author and musician Jenny Hval might represent an attempt to recon with the passion for a music scene that has been effectively poisoned for many listeners.

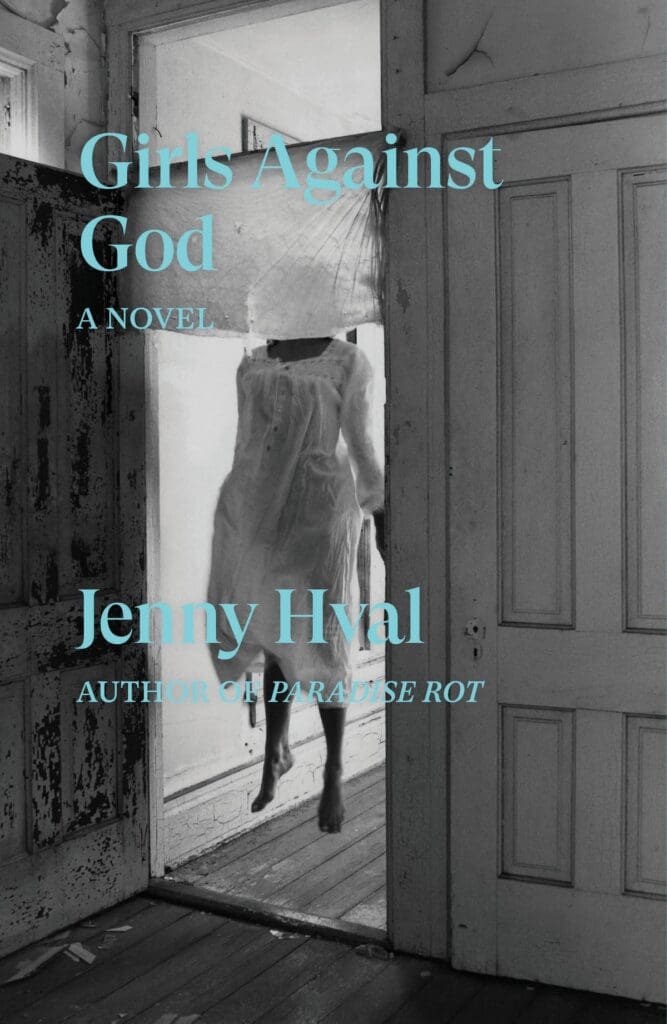

Girls Against God (230 pages; Verso Fiction) is an experimental novel that blurs the line between memoir and fiction, film theory and feminist treatise. Our unnamed narrator grew up in the highly conservative Southern region of Norway and spent some of her teenage years playing in a black metal band; the same is true of Hval, who once fronted goth metal band Shellyz Raven. As the book opens, the narrator is drawn to black metal because of its rejection of Christianity and capitalistic values; she also sees the genre in the Norwegian lineage of grim art that includes Edward Mvnch (the narrator is haunted by Munch’s painting Puberty and its suggestion of a young girl shadowed by a possibly sinister force). While our narrator initially flocks to the genre because of its talismanic power as a symbol of youthful rebellion (“The metal band also attempts to drive out the Christianity, with lyrics, guitar riffs, dark bass lines and a MIDI church organ that sounds broken, like tonal upside-down cross”), she eventually becomes disillusioned by both the limitations of live music and the unsavory fans such extreme music can attract. Hval also writes frankly about the kind of mellowing that occurs when the black T-shirt set eventually attends college and advances toward middle age:

Our hair, which for most of us at some point was long and black, mine even on my driver’s licence photo, and was modelled on capes or lowered stage curtains, has returned to the colour of its roots; our hairlines have receded; strands from our bald spots have run down the shower drain, down to the underground where they came from…Our provincially black clothes were long ago donated to charity shops, Christian thrift shops with a saviour complex.

The black metal scene changed over time as well—it had to, in the wake of the horrific crimes committed by its musicians. The narrator admits as much: “Black metal is world famous now, but it has washed itself clean of subculture, the way social democracy rinsed off socialism.” But it’s perhaps misguided to approach the novel as an example of autofiction or a chronicle of a musical genre’s development; the book is fair more concerned with the realm of ideas than depicting our narrator’s coming-of-age. All the same, the occult imagery at the heart of much of black metal serves as a fascination for her well into adulthood; to her, witchcraft proves a source of inner strength, and a lifestyle that means “resisting power, asking questions, hating God.” To that end, she recruits two other young women, named Venke and Terese, to form a kind of art collective—two women whom we suspect may merely be a product of the narrator’s mind. The trio discuss such heady subjects as the nature of art in the 21st century, the intricacies of witchy rituals, and the legacy of Mvnch, among other topics. “Maybe the only way an artist can escape capitalism and patriarchy today,” our narrator muses, “is to use art to disappear as an individual.”

And this is where readers anticipating concrete scenes dramatized with characters and actions may find themselves frustrated; Girls Against God only grows more abstract and theoretical as it progresses, like a black tape violently unspooling from a cassette reel. The last third of the novel might be best described as an unreliable transcript of an experimental short film, one possessed by a dark magic: “Shots of animals, big and small, pausing and breathing rapidly in and out through their nostrils…Mushrooms and flowers stretch toward the hiking boots, the hooves and the paws that trample the landscape.”

Yet one suspects readers drawn to more experimental literature will feel strangely at home in Jenny Hval’s novel. For all of Girls Against God’s baffling imagery and cryptic dialogue, the narrator registers as an individual longing for an existence outside the binary of light and dark, good and evil; a voice oppressed by a lifetime of being told it must be saved because it is lost, one that sees in the archetype of the witch not a heretic or a deviant but something more elemental: someone who is free.