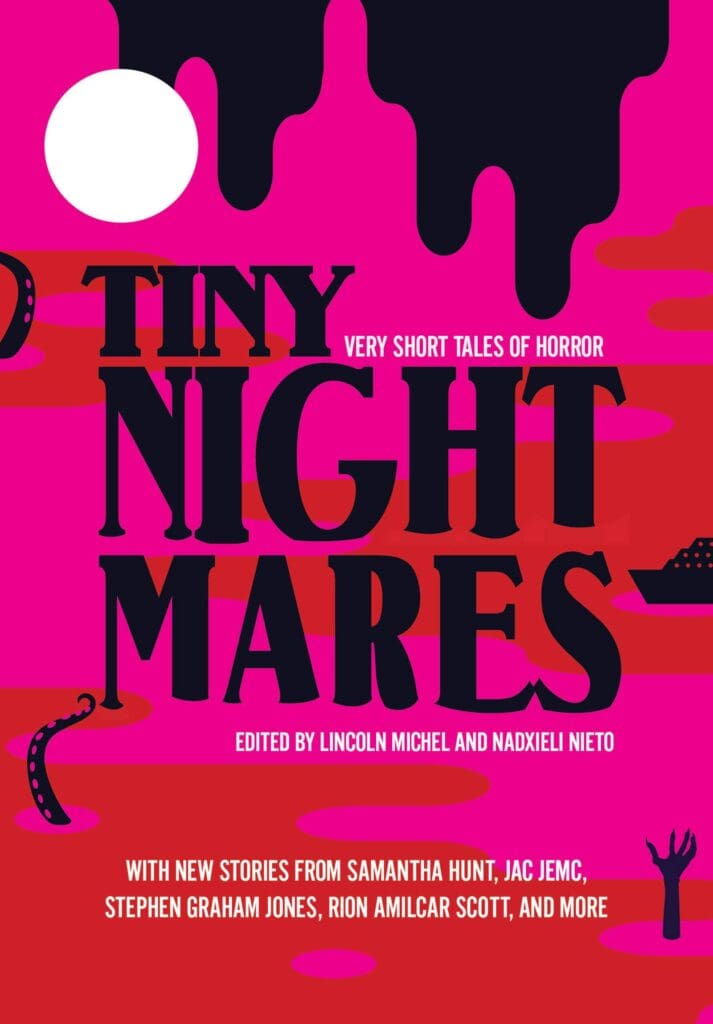

2020, with all its horrors, may have given Halloween a run for its money this time around. The holiday’s circumstances themselves this year are scary enough to substantiate a scary story—kids stuck at home with parents, or otherwise risking an uptick in COVID-19 transmission by taking part in the festivities. Some who prefer to consume more uplifting content in troubling times may find the book ill-fitted for 2020, but if like me horror is a genre you hold near and dear, Tiny Nightmares: Very Short Stories of Horror (Catapult; 289 pages; edited by Lincoln Michel & Nadxieli Nieto) is a great collection to escape into. Topping out at nearly 300 pages, but containing more than forty stories, Tiny Nightmares lives up to its title. Although the fleeting, unresolved nature of some of these narratives may posit that not every piece is suited for the less-than-1,500-words format, many of the grotesque, campy, and dystopic stories in this collection, once read, stay with you.

The collection contains a robust variety of refreshingly bizarre ‘creatures-lurking-in-the-dark,’ tales such as a shapeshifting being that is a captain’s prosthetic leg by day and a murderous ship wanderer by night (Brian Evenson’s “Leg”), or a possessed cat that crawls out of the throats of a witch’s granddaughters as they slumber (Andrew F. Sullivan’s “Grimalkin”). However, most of the haunts come from paranoid visions of the future or the horrifying problems that social or economic inequities and environmental degradation create.

The environmental stories imagine the various harrowing ways in which humans respond or adapt to Earth’s climate crisis. In “Veins, Like a System,” by Eshani Surya, the manager of an oil company undergoes “early petrochemical therapy,” allowing a doctor to inject him with the “oil, viscous and strangely red-black” which will allegedly stimulate his heart, eyes and lungs. The protagonist grows increasingly aggressive; meanwhile, images of animals victim to oil spills populate his mind. In the end, when fishing through his closet, a belt buckle smacks him in the eye and sends oil oozing down his face, even as he tries to hide it from his wife. Surya gets at our willingness to internalize the very things that harm us. In the story’s world, oil runs through the veins of our bodies, just as it does in reality through the foundation of our nation’s economic system, and through pipelines across the surface of the country.

In “Joy, and Other Poisons,” Vajra Chandrasekera offers an intriguing companion to Surya’s story. Both narrativize environmental crises with the focalization on the body, but instead of injections, Chandrasekera’s story involves extractions. In this dystopian horror story, the majority of society has resigned itself to an apocalyptic climate fate, literally “milking” themselves free of emotion. The discovery of a new gland in the back of the mouth that can be drained to induce an emotional numbing leads to a harrowing solution for facing the end of the world with a sense of peace:

It has to be done one fang at a time, with plastic collection vials no larger than a thumb. It takes about half a minute to drain each side, uncomfortable but intimate, and pleasurable in that subdued way left to us after we squeezed fierce joy out of our mouths and poured it down the sink. We are pleasantly anhedonic. It aches a little.

Beyond environmental matters, Tiny Nightmares contains a few dozen worthy scares borne out of an awareness of the world’s social ills, such as in “We’ve Been in Enough Places to Know,” by Corey Farrenkoff, which deals with squatting in buildings with septic swamps and the creatures that lurk in them, or in “Caravan” by Pedro Iniguez, about the horrific lengths a mother goes to feed her son while journeying from Guatemala to the U.S.-Mexico border. Also intriguing is the collection’s several stories that experiment with different narrative structures, including a story told through the emails between a new mother and her evasive neighbor who collects her surplus breast milk under a guise that quickly becomes suspect, as well as a choose-your-adventure story centered on a woman confronting her husband about what he’s doing all those nights when he doesn’t come to bed.

Although in the current climate a collection often driven by a fear of the future may feel inappropriately thrilling—not unlike getting on your computer and streaming Contagion right now—Tiny Nightmares is balanced by supernatural, viscerally terrifying stories that strum strings less tied to reality.