In 2004, when I was first old enough to cast a ballot in a presidential election, I lived in a small Vermont town, population 1,136. It was home to farmland, a cemetery, a snowmobile shop, a church, an elementary school, and a town hall that most days sat empty and unused. The leaky clapboard house my three roommates and I rented was shared with mice that ate through our cupboards and a badger who lodged in an unfinished back room. My roommate Margaret used to sunbathe on our lawn to the occasional honk of a passing car; we all enjoyed cigarettes on the porch, puffing our smoke into the world, watching it drift to someplace far away. To counteract the cigarettes, I liked to take long runs through the dairy fields, stealing some time alone up and down the dirt roads, through the undulating green and the snow. On Election Day, the start of Vermont’s interminable gray November, I slipped my ID into my sports bra and took off running into the fields on a route that would deliver me right to the town hall where I could vote before returning home to change and head to class.

Inside the town hall, I was greeted by a volunteer dressed in flannel, who gave me a piece of surprisingly large paper and pointed me toward a row of curtained cubbies. The curtains were made of tattered red, white, and blue fabric draped over an old curtain rod, and in each cubby a pencil was tied to the table with a long piece of yarn. I made my choices and folded up my ballot small enough—which took several creases—for it to fit into the slit of the padlocked wooden ballot box. It was all so analog and wonderful. I waved goodbye to my fellow voters and the volunteers, to whom I felt deeply connected in the moment, regardless, I felt, of who we were all voting for. As I left, one of the poll volunteers, an octogenarian with a wide smile and a slight hunch, handed me a handmade popcorn ball wrapped in cellophane. Voting even came with party favors. Democracy! I was entranced, I was hooked.

And then the results began to roll in.

I had voted for John Kerry. I didn’t love Kerry but I hated George Bush and all his administration stood for: imperialism, racism, idiocy; a thirst for money and for war, all in the name of our supposed protection. (In this way, my first vote—something that had been hard-won by generations before me—was a lesson in settling.)

My friends and I had been so certain the presidential election would go our way. Our class had started college in the fall of 2001, just weeks before 9/11, and our sophomore year was marked by war. Our whole emergence into adulthood was mired in violence and senselessness and vendetta. We’d do something about these garbage politics dominating the airwaves because, goddamn it, we could vote. My friends Sam and Andy threw a voter registration party; they printed out registration forms from all fifty states and set up a table by a trashcan full of punch. Sam had become certified as a notary the previous week so he could notarize the forms and mail them the next day. We were going to vote and we were going to win.

When they called the election, we were devastated. Four more years, of this? (We had no way of knowing, even then in our despair, just how long the shadow of that result would stretch.) We lost. That’s what democracy is—accepting the possibility that you’ll be on the losing end of the tally pile. The next day, a group of us gathered to mourn and smoke cigarettes outside the dining hall. My friend Kevin read Ginsberg’s Howl out loud, screaming into the darkening day. It felt poignant at the time, and then quickly and for many years after, I remembered it as a baroque absurdity. Now I look back at that moment with tenderness. “Who fell on their knees in hopeless cathedrals praying for each other’s salvation and light.” At least we felt it.

And we were looking for precedents, for guideposts, for elders to help us navigate from the misery we felt toward some brighter future. Our professors didn’t much have what we were looking for, nor did our parents. I had a crush at the time on an older writer I’d met at a party who sometimes came into town offering motorcycle rides and compliments and tales of his adventures. After the election I logged onto a library computer and, helpless and hopeless, wrote him about the “sad sad times.” “Don’t worry about the sad sad times,” he replied. “Or, more correctly, worry but don’t despair. We have to fight harder and more fearlessly.” I felt acknowledged and like I’d been given a mission.

Since that day in November, I’ve voted in a school cafeteria, in a school basement, in a church, in my own garage. Each time I marvel at the persistently analog nature of the vote and feel, however fleetingly, that I am stepping into some collective current, turbulent and unfinished and sacred. I recall that warbling enthusiasm in my chest when I first voted, like I had been handed a torch to carry forward.

Democracy is messy as hell and, in an increasingly antiseptic world where so many rites have been converted to transaction, I can find in its messiness something to celebrate.

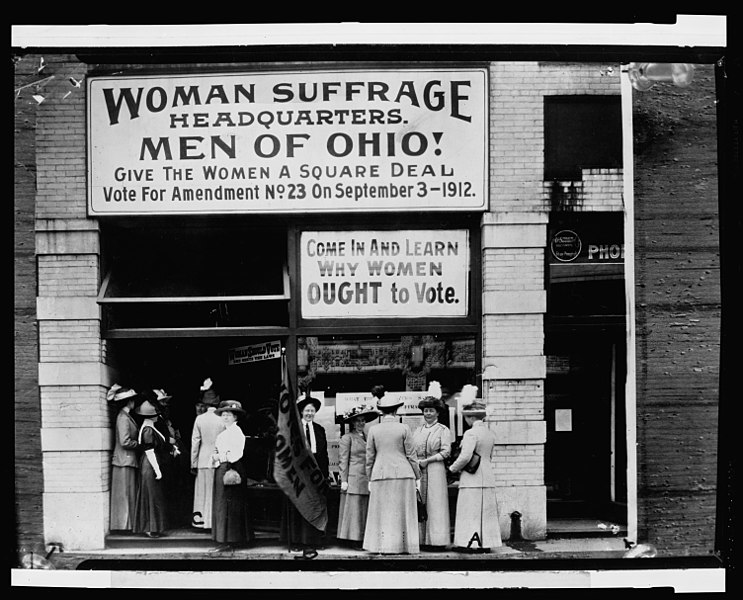

As in: when my great grandmother arrived to this country from Greece in 1914, no voting for her. As in: my grandmothers were both born when women weren’t allowed to vote, but one of them lived long enough to watch her granddaughters cast their ballots.

For many years, I’ve worked at a school for newly arrived immigrant youth, many of whom arrived (though under far more dire circumstances) like my great grandmother did—alone, raw with hope and with the uncertainty of their futures, their first moments in the U.S. lived from within the inside of a detention cell. Even when they turn eighteen, the vast majority of my students won’t be eligible to vote, and won’t ever be able to vote unless (or until) our immigration laws change dramatically. (A hope horizon can recede so quickly.) The asylum process is being eviscerated, immigrants are being harassed and beaten and murdered in the streets and in their schools and in their homes, they are dying in detention and being forced to wait interminably for “their turn.” Though they live here and work here and pay taxes, my students seem to have fewer protections every day. On the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United Sates, democracy is, in so many ways, a myth, a sham. Yet another reason to fight harder and more fearlessly.

To secure the Vote for Women, suffragists lost jobs and partners, were shunned by family members and friends and excommunicated by their churches over the right to vote; they were arrested and laughed at and called heathens and beaten and slandered and force-fed in their prison cells. “The present agitation,” Susan B. Anthony proclaimed, “rises from the demand of the soul of woman for the right to own and posses herself.” A radical notion. Prison sentences were long and harsh for suffragists; their food was infested with worms; guards brutalized them while many Americans looked on in scorn. My ability to take a little jog to my polling place and cast my ballot required so many before me to fight without fear—or to fight with the fear that neglecting to do so would lead to things staying the same. How easy human beings can forget the people who came before us, and the debts we owe.

“It was we, the people,” said Anthony, “not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. … Men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less.” A 1917 protest sign: “They say we are a democracy, help us win a world’s war so that democracies may survive. The women of America tell you that America is not a democracy.” How many people today, amid our voting restrictions and our gerrymandered districts and our electoral system and our impossible immigration exclusions, feel the same way?

Like all history sealed into our textbooks, the stories we tell about women’s suffrage also deserve some revisiting. For while the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was a victory for some, it was, as social victories so often are, won at the expense of others. It was a victory for white women, who betrayed their fellow black suffragists. This fact is often erased, and is sometimes cast as the slow, piecemeal nature of progress—first things first, then the next things after that.

“Throughout much of the first generation of the women’s suffrage movement,” writes Rosealyn Terborg-Penn in her book African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, “Blacks attempted to demonstrate that disfranchised African Americans and disfranchised women shared the common plight of oppression. In doing so, they aimed to unite the two groups for a greater driver toward universal suffrage.” But when unity became less politically advantageous, the dominant white women’s suffrage activists threw the goal of universal suffrage out the window.

Once the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, black women suffragists appealed to members of the National Women’s Suffragist Association (now the League of Women Voters) for support. “As many Black female suffragists suspected,” wrote Terbord-Penn, “white women voters ignored their plight. Having earlier encouraged Black women to join the movement in order to bring Black male voters into the women’s suffrage camp, white suffragists then abandoned” them.

If a myth is a story we write backward to explain—to justify—the present, then too often the history we teach in schools is the stuff of myths—whitewashed, saccharine, clean narratives of righteous struggle tied up with a bow. Many of us were taught that the women’s suffrage movement was led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and that it began at the 1848 convention of Seneca Falls. Yet few revolutions have such a clear genesis. In her book The Myth of Seneca Falls, historian Lisa Tetrault reveals that though the Seneca Falls Convention certainly happened, Stanton and Anthony fashioned the event into an origin story some twenty-five years after the fact in order to control the suffrage movement narrative. “The mythology Stanton and Anthony created has, in turn, sanctified them,” writes Tetrault, “so that it can, at times, be uncomfortable to see them as complex political actors, driven by an ambition to lead and animated by the self-assured knowledge that they knew best.”

How do we celebrate progress and honor our predecessors while also acknowledging that progress’s casualties and its tactics of exclusion? It would be easier to do this is if we were better trained to do so early on—that is, if our schoolbook history was approached with some degree of complexity. You know who, if given the chance, understands the complexities of politics better than any of us? Teenagers, the students themselves. They are weathervanes of sincerity and hardwired for justice. What’s fair, what’s right, whom should we trust, whom should we believe? Ask a teenager, she’ll tell you. But we rarely ask.

Just because someone is legally permitted to vote doesn’t mean they will be able to. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment passed, making it illegal to bar people—defined as men—from voting based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Still, many black men were barred from voting. In 1887, Native American men were eligible for citizenship so long as they disenrolled from their tribes; the Citizenship Act of 1924 granted voting rights to all Native Americans, but it wasn’t until a 1948 court case that actual voting rights were secured, and even then, not in every state until 1962. In 1920, the Women’s Suffrage Amendment was passed, but still, black women and other women of color were largely barred from voting. In 1943, Chinese Americans won the vote. Until then, the laws hadn’t fully recognized them as citizens, which is to say, people.

Today, many Native Americans still cannot vote because some reservations do not use formal street addresses; thus, their voter registrations are rejected. Tribal ID cards aren’t valid forms of identification according to the Voter ID laws in many states. Since 2010, fifteen states have used the specious specter of voter fraud to launch stricter voting laws, requiring a government-issued photo ID and so setting a bureaucratic hurdle that disproportionately affects low- income people and people of color. Meanwhile, the national Republican State Leadership has redrawn voting maps in places like Ohio to keep a stranglehold on power there for years to come. “As a result of the new map,” writes Alora Thomas-Lundberg of the ACLU, “Republican candidates earned 51 percent of the statewide vote in 2012, but secured 75 percent of the state’s congressional seats.” Earlier this year, courts lifted a decades-long ban on Republicans’ use of “ballot security measures,” which is Republican-speak for voter intimidation.

It’s so important to name that things have gotten better. But has anything really gotten all that much better? Despair edges in. These hopeless cathedrals, us down on our knees.

The 2016 election casts a terrible heap of shadows, one of them being that too many people have been tricked into believing they witnessed the beginning of a catastrophe, rather than a subsequent chapter of a catastrophe already underway. Because we teach such tidy history in our schools, all steady arcs and epiphanies and heroes and villains, this kind of thinking is an easy trap. But November 6, 2016, took a magnifying glass to what was already there and enlarged those injustices to Godzilla-size.

Everyone has a story about the morning after. Mine was we were set to host about thirty visitors at our school’s annual open house (that we’d scheduled the open house the day after the election was, in retrospect, an act of hubris.) Who did I know who had slept? Who, that early morning, wasn’t walking around as if on a faraway planet’s sterile moon? I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I bought myself a rare cup of coffee. (I’m a tea drinker, but, desperate times.) Outside the coffee shop an unwell woman shouted obscenities at no one in particular, and took her empty beer bottle and flung it against the curb, where it shattered.

Many of our students had predicted the election’s outcome long before it came time to vote. So when they came to school they were angry, and bereft, but, unlike many of their teachers, not particularly shocked. Their concerns were pragmatic and urgent. Were they safe out on the streets, they worried, in their homes, in this country? Fair questions. No one was quite sure what to do with her rage or sadness. Students began painting their faces, making protest signs from scrap paper and recycled cardboard. They marched down Oakland’s Telegraph Avenue, cheered on by shopkeepers and passersby.

“They’re going to send the Salvadorans home,” one student said to me.

“I told you so,” said another. “I told you he would win.”

When the election was called the night before, the California polls hadn’t even closed yet. The pizza we’d ordered had just arrived.

A myth: our vote counts.

A myth: our vote doesn’t matter.

“Did you expect us to turn back?” yelled suffragist Elsie Hill toward an approaching mob at a 1917 demonstration. “We never turn back … and we won’t until democracy is won!”

Democracy is spoken of as this absolute entity, this inherent good. But like all human inventions, it is only as good as the people upholding it.

The vote: how can it be true that something is sacred, and sullied?

How do we acknowledge the criminal, restrictive state of things while also holding on to the possibility that there is, somewhere in this vast dungeon, a little shard of light? What’s hard is to continue to believe that the shard of light will ever become anything more than a shard of light.

“This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen,” wrote Rebecca Solnit. “It is also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both.” Solnit also said that a vote isn’t a Valentine, but a chess move. This serves as a reminder to me that the immense privilege of being able to vote in this powerful country means that I should wield it. But it would be nice to feel like a single vote could be both a chess move and a Valentine.

I felt as much in 2008. For me, the world was plumped with hope. I drove to Nevada to campaign for Obama, and, at the Reno headquarters, was instructed to drive an hour west, and then once there, I was dispatched another hour south into the flat, dry, painterly hinterlands of the southern state. My coworker Diana and I went door- to-door in the trailer park communities to speak with people about the upcoming election. One woman told us Obama spoke with a forked tongue. Another proclaimed that there was no option but Obama. Yet another expressed concern Obama would take her guns away, based on an article she’d read in a magazine. (The magazine, which she showed us, turned out to be a gun catalog.) One man we spoke to was a veteran who wanted a candidate with military experience. Another guy was on the fence; was Obama too young to run this country, too green? As we walked the dusty roads with our clipboards, dogs rushed from their porches and from under their trailers, howling, nipping at our heels, forcing us, from time to time, to run for it and pray. I was back in that hurtling current of history and of purpose. You must fight harder, and more fearlessly.

And since then? That rushing slipstream can be hard to come by. Some days, seeing all the ways our country, our world, rips its people to shreds and brings us to our knees, I catch myself feeling that perhaps it’s best we all just burn so the Earth can have itself back without the human scourge.

The author Alexander Chee wrote on Twitter: “Your cynicism is only ever an in-kind donation to your opponent, posing as independence.” And a few months later: “After a week of holiday conversations about the election, I just want to say cynicism poses as rebellion while supporting the status quo.”

“A radical idea: vote your conscience in the next primary,” read a recent op-ed in the Texas Observer. We are so focused on who is electable that many who would vote Democratic are not voting according to what they want, but according to what they think other people will want. I like this candidate, but I don’t think he/she could win, says my father, my godfather, so many people on the news and on the internet and at the dinner table. How can anyone stand a chance of winning if so many insist he or she or they can’t win?

A myth: “Perhaps this country just wasn’t ready for a black president.” This is a thing certain people sometimes say; they generally say this when no people of color are around. Perhaps we’re not ready for a woman president. A radical. A socialist. A Latino. Someone so young. A woman of color. This sets my skin on fire. It sets my skin on fire while trawling Twitter, at my extended family’s dinner table, in an imagined conversation on the street. They won’t vote for her. For him. This amorphous they, this them. Who are they? “We are they!” my brother and I insist to our dad one night at a bar. “I am they!”

This bloodless calculation isn’t the chess move Solnit is talking about. And isn’t it the opposite of fearlessness? Of course there’s so much to fear. But if we act only in fear, don’t we just end up with more to be afraid of?

“A better way to do this—the way a primary is supposed to work,” the op-ed reads, “is for each voter to support the person they feel is the best candidate, under the theory that if enough people agree, they probably are the best candidate.”

Did people struggle for my vote—did people get trampled and bloodied and arrested and force-fed and betrayed and left behind to struggle alone—so I could imagine what some hypothetical person far away might be imagining that some other hypothetical person wants in a candidate? Or did they struggle so I could vote my goddamn heart? I’ll never know for sure, but I’ll choose heart every time.

In 1920, a group of women marched toward the New York Metropolitan Opera to force President Woodrow Wilson’s hand into calling a special session of Congress to discuss the Vote for Women. They were met by the police. Suffragist Doris Stevens recalled: “Clubs were raised and lowered and the women beaten back with such cruelty as none of us had ever witnessed before…Women were knocked down and trampled under foot, some of them almost unconscious, others bleeding from the hands and face; arms were bruised and twisted.” The New York Times headline the next day: “200 Maddened Women Attack Police With Banners and Fingernails.” They were “maniacs who should be institutionalized,” an op-ed read.

Why aren’t more of us—why aren’t I?—in the streets, putting our bodies more fully on the line for voting protections, for expanded voting rights, for a national holiday on Election Day, for a pathway to citizenship?

It’s helpful to imagine what could come of it. One day, if we fight hard and fearlessly enough, more of the barriers to voting—all of our own making—could come crashing down. Our cathedrals needn’t be so hopeless. Because the young people I know—so long as we teach history rather than myth and don’t infect them with our cynicism—will lead with the heart at the ballot box. And I’ll be there, passing out the popcorn balls.

Lauren Markham is a fiction writer, essayist, and journalist, and is the author of The Faraway Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life (Crown), which won the 2018 Ridenhour Book Prize, the Northern California Book Award, and a California Book Award Silver Prize. You can read her essay and more great nonfiction in Issue 118.