The month of June has been one of the most tumultuous months of 2020—and that’s saying something. You’ll find some of the Staff Recommends in this installment touch on some relevant themes, including a seminal film from Spike Lee. We also have some lighter fare on the docket for those who might be searching for momentary escapism. So without further ado:

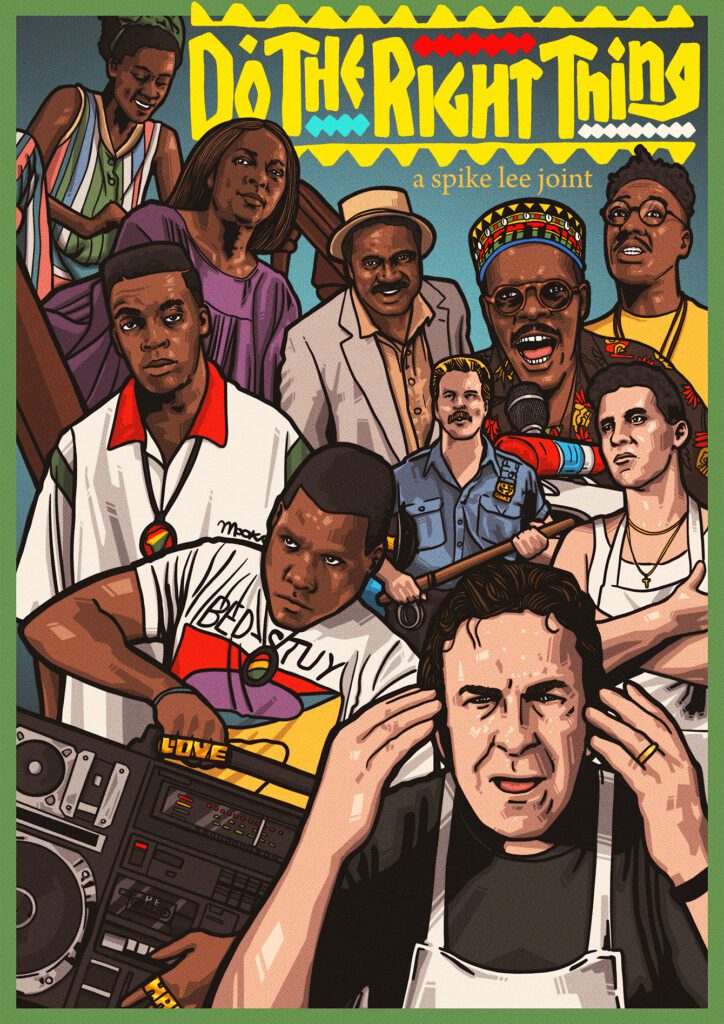

Cade Johnson, Intern: I recently watched Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing after a friend recommended it to me. I had heard about this film on one other occasion from an episode of a New York Times podcast, “Still Processing,” where hosts Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris contextualized it within a canon of films that raised critical and realistic conversations about race but were snubbed by the Academy during Oscars seasons for films that presented more watered-down and white-centered perspectives of race in the United States.

Do the Right Thing follows a large ensemble cast of Black residents of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, but mostly Mookie, played by Spike Lee himself, who delivers pizzas for a neighborhood pizzeria called Sal’s run by an Italian-American family. The hinge of the film’s central conflict is introduced when Mookie’s friend, Buggin’ Out, asks Sal why there aren’t any Black celebrities on the restaurant’s “Wall of Fame,” given that the restaurant sits in the middle of a historically Black neighborhood. Tensions rise on this Saturday in Bed-Stuy as Buggin’ Out calls for a boycott of Sal’s. Spike Lee’s artful slice of a neighborhood on a day where the heat is all-consuming and tensions are high addresses in a critical and honest way dynamics of gentrification, police brutality and many other aspects of systemic racism.

Beyond the nuanced and highly relevant discourse, the film is incredible for Spike Lee’s unique style, which manifests in striking cinematography and lively direction, as well as its intriguing and vibrant cast of characters. I would recommend this film to anyone. Do the Right Thing is essential viewing.

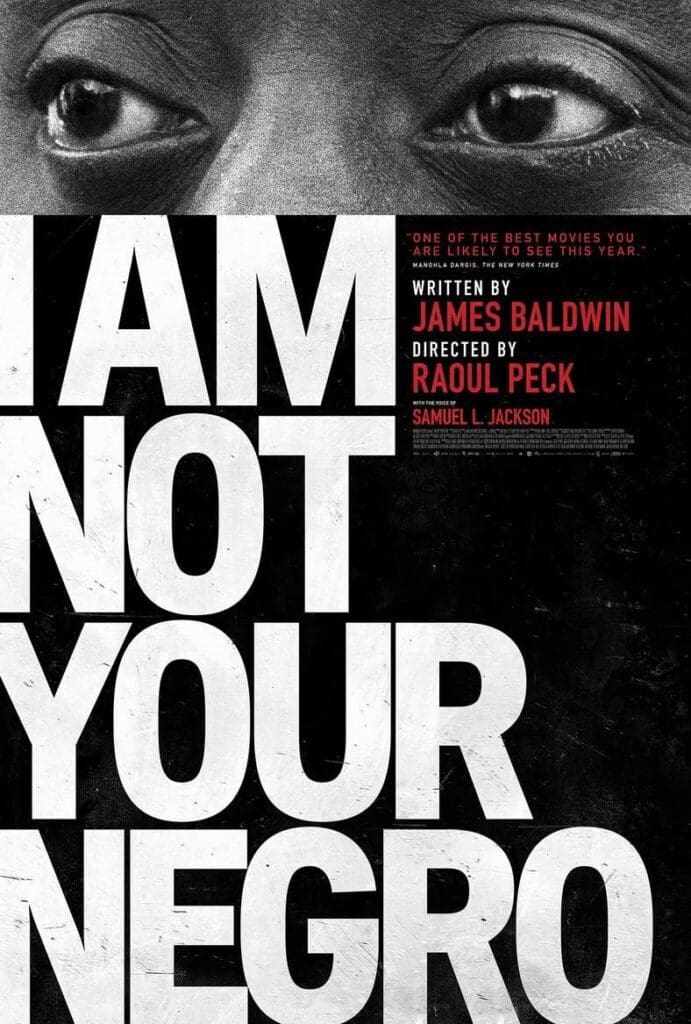

Jesse Bedayn, Intern: After writing just thirty pages of notes on his final book Remember This House—the story of America told through M.L.K. Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evans—James Baldwin died of cancer. In the 2016 documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, Samuel L. Jackson revives those thirty pages, exploring the history of race in America, through Baldwin’s words and those of three civil rights leaders.

As I write this in 2020, anti-racist protests rock America. It has become necessary to understanding what Baldwin said in those 30 pages: “History is not the past; it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals”.

The documentary’s first clips are a collage of movement. Today’s subway leaves the station, black and white railcars arrive. Buses and people busily walk across segregated cities, greeted in the next shot by the glitz of modern-day Times Square. Old reels of actors in blackface appear after images of Rodney King’s beating. Broken necks in nooses follow 1950s advertisements of white families cheerily snapping photos with their new Canons. Then a picture of Trayvon Martin. Throughout the film, the 21st century is folded onto the 20th century in a blur of motion. The viewer is left disoriented in time. Everything is now.

If I could, I would construct this recommendation for I Am Not Your Negro purely out of Baldwin’s insightful sentences, each of which seems to burst with insights, and terrible, searing truths. “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly,” he wrote in The Fire Next Time, “is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.”

The documentary reminds us that Baldwin understood humanity one layer more deeply than most others. In speech and prose, he yanked open America’s curtains and pointed with uncanny precision right to the problems that dot our landscape. To ignore his work is to miss a fine, protracted analysis of just who it is that we are.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: The quarantine season has left many of us feeling adrift in a sea of content—though I’ll admit, one upside of being unable to meet up with friends at the Alamo Drafthouse or hang out on the patio of my local brewery is that I’ve had more time to devote to conquering the backlog of unread books in my collection (in case anyone is wondering, Tender is the Night is really as great as all those F. Scott Fitzgerald scholars suggest). I also find myself contending with the vast library of streaming content at my fingertips; perhaps not surprisingly, this has at times left me yearning for a little bit of structure. My solution has been to routinely schedule mini-‘programming blocks’ for myself. For much of the month of June, I’ve immersed myself in the Hollywood releases of 1961. It’s an era in American history that couldn’t feel more distant as we grapple with a 21st century pandemic, but its cinematic pleasures are myriad: from the Technicolor acrobatics of the Sharks and the Jets in Robert Wise’s classic musical West Side Story, to Marlon Brando’s counter-culture Western One-Eyed Jacks or Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty’s teenage hysterics in Splendor in the Grass.

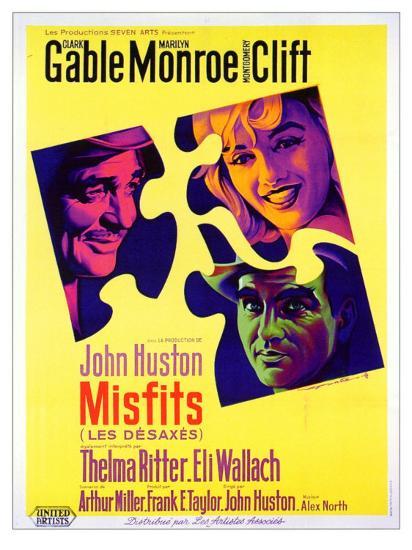

But the ’61 release that lingers the most in my mind might just be director John Huston’s The Misfits. You could say that all films are ghost stories of a kind, preserving as they do our acting legends for all time—freezing them in the season of their youth, capturing their most iconic moments for posterity; even so, The Misfits proves a particularly haunting ghost story, starring as it does three of of the silver screen’s most memorable performers—Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and Montgomery Clift—not long before each of them would meet their untimely death.

Fortunately, The Misfits showcases the trio (ably assisted by Eli Wallach and Thelma Ritter) at their most dynamic; in fact, there’s a case to be made that the film represents Marilyn Monroe’s finest hour onscreen. The script, penned by her then-husband Arthur Miller, comments on Monroe’s beauty at length but draws an equal amount of attention to the considerable sadness just below her surface appeal. In truth, there are times when these characters feel like little more than a mouthpiece for Miller as he grapples with some of those Big Authorial Questions of his day, like how men and women are supposed to manage a thing like “till death do us part,” and the true value of a man’s word, but he’s fortunate to have a cast of larger-than-life actors who imbue their roles with an indelible verve.

Montgomery Clift arrives later in the film, wearing the jeans and cowboy hat of a bull rider; his attire can’t help but serve as a callback to his first onscreen appearance in Howard Hawks’ 1948 Western Red River. In that film, Clift’s character took part in the historic first cattle drive along the Chisholm Trail circa 1866; a hundred years later, the grandeur, the myth of the American West—and all that it entails—has faded, and there’s little left for Gable and Clift’s aging cowboys to do but risk their lives riding bulls or resort to the ignoble work of rounding up wild horses to sell to companies who will turn them into dog food. These characters are misfits, to be sure, born in the wrong era, outliving their usefulness in small town rodeos and backroads bars.

But then: how many of us who make our way out West continue to be motivated by a similar feeling of un-belonging? In this way, The Misfits becomes a fitting elegy to the West. The ending gives me chills: Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable in the cabin of a truck, driving through the Nevada desert at night. Their characters are trying to find their way home under a dome of stars, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was watching the two actors ride off into a celluloid afterlife, never to be seen again. But of course, I tell myself, we can conjure them back at will; and the uncommonly sensitive approach of performers like Monroe and Montgomery Clift continue to speak to us long after they’ve gone.

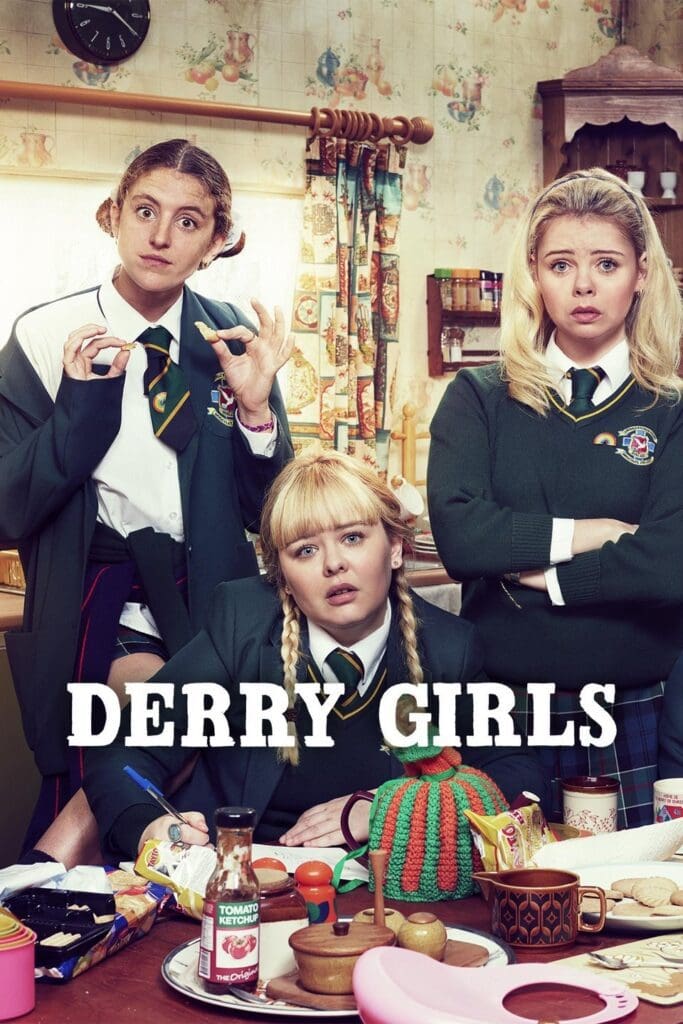

Bella Davis, Intern: I’ve said before that being in quarantine (you will not see me in a restaurant maybe ever again) makes me feel like I should be productive by picking up a hobby or learning something new. Who would’ve thought that I would accomplish the latter by binge-watching the sitcom Derry Girls? Yet, here we are. After watching the two available seasons, the most recent of which came out in 2019, I can say that I’ve learned what I would think is a fair amount of Northern Irish slang. “Catch yourself on,” which basically means “don’t be stupid,” is just a really enjoyable phrase to hear in that very distinct accent.

Set in Derry, Northern Ireland in the 1990s, Derry Girls is a teen comedy. Amid the conflict known as the Troubles, four Northern Irish girls and their British friend try to navigate all the usual challenges of growing up: romance, strict parents, and exams. We’re always aware of the conflict—we hear about bomb threats and the Irish Republican Army—but it tends to feel like background noise as we watch the group’s, for lack of a better word, shenanigans. One that stands out to me is when they almost accidentally let a bunch of old people at a memorial unknowingly eat edibles. In trying to dispose of them, they clog the host’s toilet—while one of them insists it’s the only way to get rid of drugs—and it floods the upstairs bathroom.

The way that the show skillfully elicits laughter and feelings of nostalgia while treating the Troubles with the seriousness required is highlighted by the season 1 finale. One of the girls, Orla, who we’ve seen throughout the episode get into step aerobics, performs at the school talent show to a quiet chorus of ridicule. The rest of the group joins her on stage in support. Shots of them dancing with carefree abandon are interspersed with shots of one of the girls’ families watching a TV news report about a bombing, which the news anchor describes as one of the worst atrocities of the conflict—all this as “Dreams” by The Cranberries plays in the background, a song that begins with the lyric, “Oh, my life…is changing every day, in every possible way.”