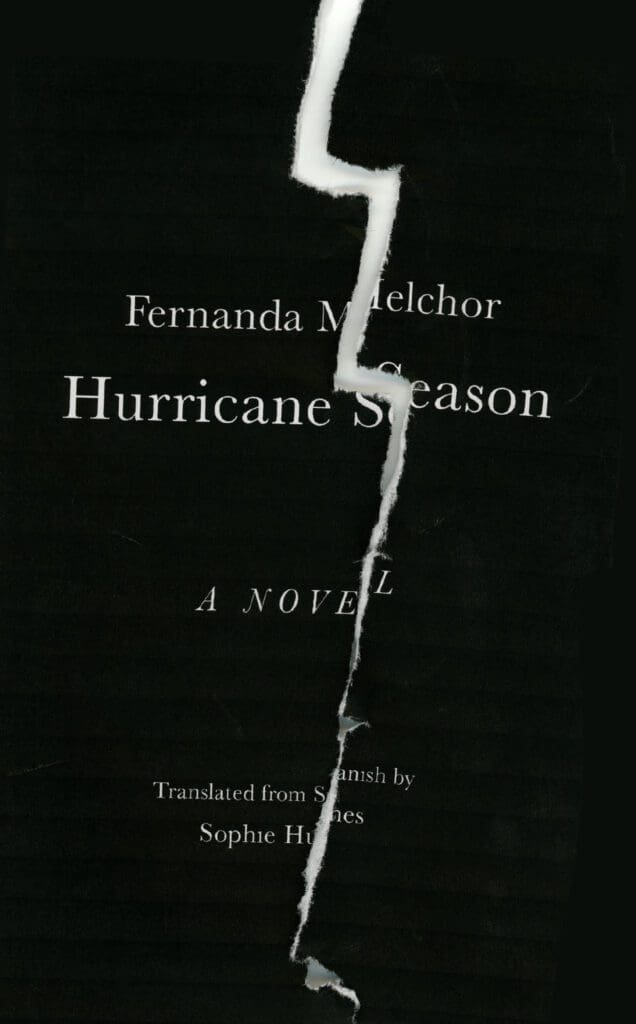

More than once did I consider abandoning Hurricane Season (224 pages; New Directions; translated by Sophia Hughes), Fernanda Melchor’s first novel. Sentences are pages long, and the ones that are not are often fragments. Many times I lost my place. I could barely see through the imagery, which is torrential yet constantly vivid. Even so, I turned its final page after only a few sittings.

The story begins with a body. The Witch, she is called. Discovered by five boys wading through a canal, she lies floating beneath a “myriad of black snakes, smiling.” From there the next seven chapters crackle, each taking on the furious perspective of a new narrator who offers his or her own insights about the murder and, more importantly, the village where it happened. Melchor writes in a third person that warps without warning into first then back to third. It’s a technique suited to her architecture of disorientation. Narrators offer uninhibited responses, justifications, and observations, while also occluding important connective information. In the second chapter we learn there are actually two Witches, mother and daughter, one dead, one alive, but in the flurry it is easy to lose track of who is who. Characters are referred to repeatedly as “dipshits” and “dumb fucks,” each slur hitting like a fat raindrop, until, eventually, the aspersions become rhythmic. But then over time, as characters become known—not merely a “dipshit,” but a son, a cousin, a friend—a humanity emerges.

Certain information re-appears: readers will wonder, have I read this before? And by Melchor’s design, you will have. There is little time for reflection or introspection, and if it comes, it does so circularly and too late.

Especially noteworthy is Melchor’s evocation of the novel’s swampy, mosquito-ridden landscapes:

…a sudden gust of almost wet wind blew in through the driver’s window, an unrelenting wind—like the imminent rains—that lashed the scorched shrubs against the ground, and in the distance, high in the sky, a great cloud veiled the sun and a lightning bolt struck the outlying mountains without a sound, not even a snap as it parted that tree clean in half, burning it to a crisp…

Her skill at imagery is maybe most evident in the brutal simile: a boy “stares blankly like a limp dick,” a fetus looks like “a chewed piece of gum,” and a charismatic churchgoer writhes like “a fumigated centipede.”

The translation by Sophie Hughes is its own triumph, navigating nimbly between the novel’s merciless dread and knife-sharp humor, such as when one character suffers a random car accident:

The doctors told him they were going to cut [his leg] off, and he said no, no fucking way, he didn’t give a shit if it was bent or missing bits of bone, it was his leg and no one was lopping it off, and the doctors said nope, no can do, that leg was as good as gone and, besides, the risk of infection was too high, but Munra dug his heels in and with Chabela’s help he escaped from the hospital the day before they were due to hack it off, and in the end he made those quack cunts eat their words because his leg never did get infected and it never died on him either, it just wound up a little bit wedged out of place, right?

The gossiping villagers ascribe darkly mystical traits to the unknown, particularly to the feminine, an obvious social critique. But the novel’s real horror comes into stark focus in the second half, by which time readers may be committed. Melchor describes rape, long-term familial abuse, hardcore pornography, and bestiality. The sixth chapter serves as an unsparing portrait of male sexuality, both its violence and fluidity—the latter of which is especially significant, as it is rarely depicted as it is here. In Hurricane Season, male sexuality is mired by shame, cruel denial, and self-hatred. The characters’ perversity, as well as Melchor’s precise grasp of it, is hinted at in the following passage where a character called Brando encounters a young boy:

The boy’s lips were pink, that’s what stood out more than anything… [Brando had] never come across another person with lips that color… He was sure that the boy’s nipples, concealed under the fabric of his t-shirt, must be the same rosy tone, and probably tasted of strawberry; they’d probably bleed strawberry syrup instead of blood if someone dared bite them.

The forbidden shadows every page. The Witch represents a taboo lifestyle; sexuality is a dangerous secret; and amid the characters’ own evasions, we find that the human mind, too, may be its own haunted room: enter if you dare. Once in the Witch’s house, a character wonders “who’s got the balls to enter the room upstairs?” Melchor seems to be asking the same of her readers. Who dares to “rummage through those tumble-down rooms”?

Many readers may not be prepared for the pitch blackness inside. And yet, as a storm rages around us, you’ll need somewhere to hide out until it passes.