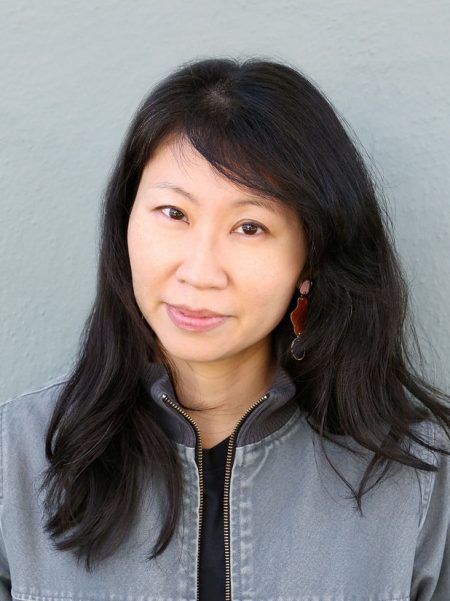

Chia-Chia Lin’s debut novel The Unpassing (FSG) was released last year to widespread acclaim (it was named one of the Best Books of 2019 by TIME, The Washington Post, and Esquire). Her short story “Ring Around the Equator, Pockets Full of Acres” was featured in the Bay Area issue. And soon Lin will be teaching a Fiction Workshop that you can apply to now. Lin recently shared her thoughts on the Writers’ Workshop process, as well as some of the pitfalls students can avoid.

ZYZZYVA: What do you think a Fiction Workshop can offer writers who feel their piece is near completion or a final draft?

CHIA-CHIA LIN: Regardless of where you are in your work, a writing workshop offers a chance at connection with other writers, which I know from personal experience can be a really hard thing to find outside of a structured degree program or while you’re working full-time. It’s an opportunity to talk about writing with other people who are deeply interested in it, who share a base level of commitment to it, and who will apply that energy to reading your work, all of which are gifts. You’ll also be pushed to consider other people’s writing in a more analytical way—to figure out how a piece is working or not working—and that’s a type of practice that is essential to becoming a better writer.

That said, I do think that workshops tend to be most successful when people come in with a sense of openness and possibility. If you truly believe your piece is finished, you might not get as much out of the experience as someone who is in a more exploratory phase. Given the choice, I’d always submit a work that I have real questions about, or that feels blocked, or that craves fresh insight.

Z: What are some pitfalls that folks should be wary of or avoid in order to make the most of a Writer’s Workshop experience?

CL: It’s always hard to hear what any one person thinks of your work, much less what eight people think of your work all at once. To the extent that it’s possible, I’d suggest trying to listen to other people talk about your work without jumping to immediate conclusions. Because we’re vulnerable people and because writing is a vulnerable act, it’s really easy to make drastic mental leaps like, “I need to throw this story away,” or, “No one understands what I’m trying to do.” And that would be a shame because that sort of thinking forecloses real possibilities for your work. I think that the processing period during and following a workshop is surprisingly long; it’s not limited to your time in class. One person might make a passing comment that, weeks or months later, turns out to hold a kind of key to your story. But for that to happen, you really have to allow things to sit in your mind.

Z: What’s a book that has inspired you in your own creative process?

CL: When I was a child, I came across Betty Edwards’ Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. The book was a bestseller when it came out in 1979 and soon after became an art class fixture. What captured me then, and still does now, were the practical lessons on how to see an object if you wanted to draw the object as it truly was. There were exercises on reproducing an illustration by first turning it upside down before you copied it, or on breaking down a face entirely into the shapes of its shadows and highlights—steps that forced you to defamiliarize a thing, so you could no longer rely on your notions of what the thing was supposed to look like. When I’m having trouble with description in my writing, I often try to see things in this way (what does the negative space around the slouching character look like, what shapes are made when the sun hits the roof), in order to get past the shorthand and arrive at something closer to the truth. The book includes before-and-after drawings (before being taught to see by Betty Edwards, and after) that are so drastic as to be thrilling and also slightly unbelievable, though you want to believe them, and do.

Don’t delay—apply for Chia-Chia Lin’s Fiction Workshop before it’s too late!