May, we hardly knew you! Yes, it seems we are well and truly in the midst of summer now, which means we’re gearing up for our Annual Fundraiser & Celebration on June 21st. But we’re also taking time out to share what ZYZZYVA recommends this month—a roundup of the works we’ve been reading, watching, and listening to:

Julia Matthews, Intern: While I’ll admit I’m often one to play songs out of order, hitting shuffle or getting distracted, I relish an album that begs to be listened from start to finish. Tierra Whack’s dreamscape Whack World is one such project. Released a year ago this spring, Whack World is Whack’s debut visual-album. On the fifteen-minute record, each song lasts just one minute before the rapper launches into a new one. It’s maddening, and it’s genius. Whack’s album is ripe with infectious hooks, pulling the listener into groove after groove only to truncate each song, never landing on the satisfying resolution our ears are trained to anticipate. I’m left with the sense that her music is larger-than-life: if her songs were forced to shrink by resolving to an end, it might be detrimental to their melodic contagiousness. Or perhaps the music is too potent, and hearing a song’s ending could be dangerous for the listener.

Julia Matthews, Intern: While I’ll admit I’m often one to play songs out of order, hitting shuffle or getting distracted, I relish an album that begs to be listened from start to finish. Tierra Whack’s dreamscape Whack World is one such project. Released a year ago this spring, Whack World is Whack’s debut visual-album. On the fifteen-minute record, each song lasts just one minute before the rapper launches into a new one. It’s maddening, and it’s genius. Whack’s album is ripe with infectious hooks, pulling the listener into groove after groove only to truncate each song, never landing on the satisfying resolution our ears are trained to anticipate. I’m left with the sense that her music is larger-than-life: if her songs were forced to shrink by resolving to an end, it might be detrimental to their melodic contagiousness. Or perhaps the music is too potent, and hearing a song’s ending could be dangerous for the listener.

It’s this kind of imaginative spirit that Whack World inspires — Whack is unafraid of dwelling in the nonsensical. The audiovisual experience (directed by Thibaut Duverneix and Mathieu Léger) is outrageous, blending the playful with the dark. In “Pet Cemetery,” she sings in a graveyard full of animal sock puppets, lamenting the loss of her dog, perhaps in tribute to the death of her friend and fellow Philadelphia rapper, Hulitho. She often contorts her voice, adopting a deep and garbled mumble or a grating twang, and compliments the grab-bag variety of her sound with fantastical outfits and settings throughout the visual album.

Whack World is not fifteen minutes long because Whack doesn’t have much to say. Rather, it’s an exercise in less being more. She has listeners melodically hooked, but refuses to fill out each song beyond the exact sufficiency of her razor-sharp lyrics. In the visual album, Whack captivates with every entrancing scene, but knows she can cut off each one only to plunge the viewer into another. Whack’s music is bubbling into the mainstream, buoyed by critical acclaim for much of her work. To listen to Whack World is to flout musical conventions and embrace visceral ridiculousness. Fill in the gaps with your imagination.

Arianna Casabonne, Intern: Netflix’s Easy is an anthology series created and directed by Joe Swanberg chronicling the lives of various couples in Chicago. Now in its third season, I stumbled upon Easy from Netflix’s “Recommended” section. I will admit, most of the time the recommended section does not yield the best results, however once in a blue moon Netflix reveals a hidden gem of a show. Easy is just that. Each episode focuses on a different couple, and throughout the seasons we watch their relationships morph, experience challenges, sometimes end, and sometimes begin again. The couples include a husband and wife who decide to explore an open marriage, a young lesbian couple figuring out how feminism and emotional obstacles play a role in their relationship, and a fading comic book author as he struggles to remain current and mend the pain he has caused various women.

Arianna Casabonne, Intern: Netflix’s Easy is an anthology series created and directed by Joe Swanberg chronicling the lives of various couples in Chicago. Now in its third season, I stumbled upon Easy from Netflix’s “Recommended” section. I will admit, most of the time the recommended section does not yield the best results, however once in a blue moon Netflix reveals a hidden gem of a show. Easy is just that. Each episode focuses on a different couple, and throughout the seasons we watch their relationships morph, experience challenges, sometimes end, and sometimes begin again. The couples include a husband and wife who decide to explore an open marriage, a young lesbian couple figuring out how feminism and emotional obstacles play a role in their relationship, and a fading comic book author as he struggles to remain current and mend the pain he has caused various women.

There is a diverse and notable cast, including Dave Franco, Emily Ratajkowski, Orlando Bloom, and Jacqueline Toboni. The exploration of relationships among different sexes and races allows the show to delve into social issues as well. One episode focuses on a sex-positive feminist writer and sex worker played by Karley Sciortino. Her character refers to her sex work as a “side hustle” which she hopes will help her launch her career as a writer. In another episode, an older graphic novelist deals with a former graduate student of his who makes a comic about the time he slept with her while she was still his student. This episode addresses not only the abuse of power, but what rights artists have to share other’s stories, especially when it may be damaging to another person. Although the episodes tackle a variety of relationships and issues, they are all bound together by the setting of Chicago.

What Easy manages to capture very well is the nuance of human emotion. The challenges the couples face are wide and varied, yet the show narrows in on relatable experiences the viewer can take part in. The show’s title conveys just how naturalistic the writing and acting appear, allowing the audience to easily connect with the characters. The world these people live in feels authentic and modern, and something particularly current to our lives today.

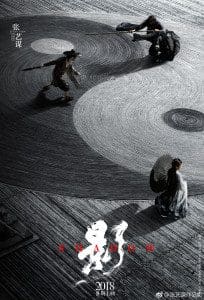

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Zhang Yimou stands as one of the select few Chinese filmmakers to achieve success at the U.S. box office –– 2002’s Hero remains the third highest grossing foreign-language film in America –– and even after the creative misfire of 2016’s (still interesting) The Great Wall, a new film from Yimou is a cause for celebration, particularly when he’s working in the wuxia genre he knows so well. Films like House of Flying Daggers and The Curse of the Golden Flower are as much about stillness as they are the swift motion of martial arts; they luxuriate in their costumes and zither soundtracks as much as their bladed weaponry and wire-assisted battles. Yimou pinpoints at each of their centers a cauldron of barely repressed emotion that gives rise to the balletic violence: when the seasons suddenly change mid-battle in The House of Flying Daggers, mirroring the characters’ relationship to each other, it somehow makes perfect sense in Yimou’s stylized world.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Zhang Yimou stands as one of the select few Chinese filmmakers to achieve success at the U.S. box office –– 2002’s Hero remains the third highest grossing foreign-language film in America –– and even after the creative misfire of 2016’s (still interesting) The Great Wall, a new film from Yimou is a cause for celebration, particularly when he’s working in the wuxia genre he knows so well. Films like House of Flying Daggers and The Curse of the Golden Flower are as much about stillness as they are the swift motion of martial arts; they luxuriate in their costumes and zither soundtracks as much as their bladed weaponry and wire-assisted battles. Yimou pinpoints at each of their centers a cauldron of barely repressed emotion that gives rise to the balletic violence: when the seasons suddenly change mid-battle in The House of Flying Daggers, mirroring the characters’ relationship to each other, it somehow makes perfect sense in Yimou’s stylized world.

His latest film, Shadow, is no exception, and fortunately it’s now screening in San Francisco. The movie finds the filmmaker truly embracing the artifice of digital cinema for an almost comic book-like aesthetic. True to its namesake, Shadow boasts a nearly black-and-white color palette, with blacks as deep and inky as the calligraphy brushstrokes we witness the characters perform. The first hour of the story gives itself over to palace court intrigue –– set during the Three Kingdoms period, it’s a twisting narrative that sees a wounded General replace himself with a highly trained double in order to scheme against the petulant young Emperor. Torn between the General and his ‘shadow’ (both played by Deng Chao, though his performance is so skilled viewers would be forgiven for thinking there are two separate actors in the roles) is the General’s wife, who finds herself developing feelings for her husband’s duplicate.

The table is clearly set for betrayal, intrigue, and tragedy in equal measure, and Yimou does not disappoint, tightening the rope for a back half full of expertly-choreographed action sequences, including razorblade umbrellas twirling in the rain, an androgynous army wielding crossbow gauntlets, and the startling introduction of blood red to the film’s stark milieu. It’s been over a decade since Zhang Yimou has delivered this brand of film –– the same gravity-defying, martial arts epic that introduced him to American multiplexes –– but Shadow operates with a confidence and grace to indicate Yimou hasn’t missed a step in the intervening years. Shadow is precisely the kind of visually lush, operatic tale that calls for the theatrical experience. I recommend Bay Area audiences seek it out while they have the opportunity.

Laura Cogan, Editor: I’m midway through Transit, the second in Rachel Cusk’s compact and rigorous trilogy of novels, and as the book centers around a period of transition, upheaval, and uncertainty in the narrator’s life, it seems somehow appropriate that I’m writing about it while still reading and still gathering my thoughts. In this volume, Cusk’s narrator (Faye) is back in London, recently separated from the father of her children, and renovating her life nearly from the ground up. The run down second floor apartment she’s purchased requires extensive work. The largest part of the project—redoing the floors—is meant to assuage the vociferous complaints of her elderly downstairs neighbors who are sensitive to all footsteps from above, but thus far has only inflamed tensions, as the noise of the construction itself outrages them. There may be a metaphor in here, but I wouldn’t want to reach at one when Cusk has done such a beautiful, intricate job of laying down each sentence just so, and layering complex themes throughout. As in Outline, most of the text is rendered through a series of conversations. The stories shared by friends, colleagues, and acquaintances are varied but rich with interconnectedness. The longing for freedom, the fear of change, the myriad ways we are shaped and hurt by our relationships with our parents and children—these all emerge at the forefront.

Laura Cogan, Editor: I’m midway through Transit, the second in Rachel Cusk’s compact and rigorous trilogy of novels, and as the book centers around a period of transition, upheaval, and uncertainty in the narrator’s life, it seems somehow appropriate that I’m writing about it while still reading and still gathering my thoughts. In this volume, Cusk’s narrator (Faye) is back in London, recently separated from the father of her children, and renovating her life nearly from the ground up. The run down second floor apartment she’s purchased requires extensive work. The largest part of the project—redoing the floors—is meant to assuage the vociferous complaints of her elderly downstairs neighbors who are sensitive to all footsteps from above, but thus far has only inflamed tensions, as the noise of the construction itself outrages them. There may be a metaphor in here, but I wouldn’t want to reach at one when Cusk has done such a beautiful, intricate job of laying down each sentence just so, and layering complex themes throughout. As in Outline, most of the text is rendered through a series of conversations. The stories shared by friends, colleagues, and acquaintances are varied but rich with interconnectedness. The longing for freedom, the fear of change, the myriad ways we are shaped and hurt by our relationships with our parents and children—these all emerge at the forefront.

Amid all this, the meta-considerations of Outline are continued as well. In that first volume, a neighbor in Athens tells Faye, “I discovered that a life with no story was not, in the end, a life that I could live.” That may be true for many of us. But it seems Cusk is asking Faye and the reader (and perhaps herself) to consider more fully what, then, constitutes a story. And in Transit, that question is more explicitly linked to the sacrifices and risks involved in our primary relationships. In one of the relatively rare moments when Faye, rather than just reporting the stories and ideas she’s listening to, steps forward and shares her own, she says, “…it seemed to me that most marriages worked in the same way that stories are said to do, through the suspension of disbelief. It wasn’t, in other words, perfection that sustained them so much as the avoidance of certain realities.”

I continue to be fascinated with Cusk’s work in these books, with the opacity of Faye, and the unusual authority and confidence of this voice and structure. It’s the kind of work that opens door upon door of inquiry, prompting me to take many, messy notes in the margins. I’m looking forward to reading Kudos next.