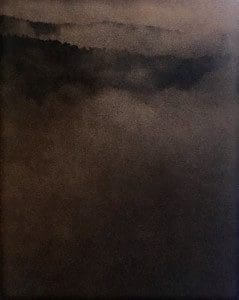

Matthew Genitempo’s forthcoming book of photographs, Jasper (96 pages; Twin Palms Publishers; available for pre-orders now), explores a region of the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas where people live apart from the well-established norms of American life. Born and raised in the Houston area, now based in Marfa, Genitempo previously worked mostly in the Southwest; however, Jasper, his first book, represents a journey he made farther east while he was an MFA student at the Hartford Art School.

The black-and-white photographs in this book capture a series of solitary men and the remote homes they’ve made in a lush and hardbound pocket of the country. The images contain an ambiguity somewhere between loneliness and solitude, documentation and imagination, and in turn reflect the ways in which a book of poetry might weave gestural narratives based in elegy and evocative landscape. Inspired by the life and work of Arkansas poet and land surveyor Frank Stanford, Jasper transcends this reference to show how the past is lost and found—and lost again—in our contemporary moment.

I met Genitempo during a recent trip to Marfa, where we talked in the Lost Horse Saloon, the Hotel Saint George, and out in total darkness at a poet friend’s house in the Fort Davis Mountains. This interview was conducted over the phone six months later.

ZYZZYVA: I want to talk about the early days when you started pushing to escape the day-to-day and drove around a lot and took pictures by going places that might be unsafe.

Matthew Genitempo: I want to say that I understood that aspect of picture-making very early on. I remember seeing Stephen Shore’s work, William Eggleston’s work and Robert Frank’s work and a lot of pictures that were made while traveling. Not so much Eggleston, but Shore, Frank, and Robert Adams, too. I think I quickly understood that photography had opened up an unknown world for them, so maybe it could do that for me. I took a couple of photography classes in high school but I didn’t really take them seriously. I learned how to use the darkroom and everything, but I was playing in bands and playing sports, so I wasn’t very interested in photography at the time. I also wasn’t exposed to those artists I mentioned earlier.

Fast forward to college, I was studying graphic design and I took a photography course as an elective, and that’s when I was introduced to those artists. Immediately when I discovered that work, I started emulating them. They were my heroes. I started going to the seedier parts of town, downtown and the outskirts of town, bringing my camera along and making pictures. Then I started going to the smaller towns in that part of the state. I started seeing my peers making work where they were actually traveling, so I wanted to do that, too. I went out to west Texas and made pictures out here. It was a pretty natural progression. From there, my first big trip when I was out for more than a weekend came when I was working a graphic design job and I took some time off, and I went out to New Mexico for the week. It felt like I was on another planet. I felt so far away from everything I knew. I didn’t grow up traveling in the car too much. We didn’t travel very often, and when we did it was to visit my folks’ farm, or if we went on a family vacation we normally flew somewhere. So I felt like I missed out on a lot of that growing up. That was the first road experience that I had. The first one that had lived in my imagination.

Z: Where in New Mexico did you go?

MG: I remember heading out and not knowing really where to go, then hearing that Gallup, New Mexico, had a lot of neon signs. That sounded like a good plan because Stephen Shore had this crazy hold on me at the time. I just hauled ass over a day and a half. I think I drove to Amarillo the first day, cut west straight down I-40, all the way to Gallup in one day, and slowly made my way back. Gallup had a lot of neon. It didn’t disappoint.

Z: I remember you talking about the point at which you were in grad school and the noted photographer Tod Papageorge came to do reviews. You were saying you had a lot of work from the West that was being reviewed and that it was a catalyst for you, along with stuff in your personal life, that pushed you east to Arkansas.

MG: Hartford is a low-residency program so we end up meeting in places all over the world. For this particular session, my cohort met in Berlin. The school had Tod Papageorge come out. Two or three months before that, I’d gone through a pretty drawn-out and significant break-up. I was still trying to make this Western work while navigating all that. I thought I had a really good grasp on what I was making out West. I printed all these pictures out and prepared what I was going to say when I got to Berlin and re-read Tod Papageorge’s Core Curriculum, because it’s a really wonderful book and I wanted to prepare myself for this critique. I’ve looked up to Tod Papageorge for a while. I really respect the guy.

I was the first to go for crit on day one in Berlin and the work was torn apart. It was quickly dismissed and it was really clear I was spinning my wheels out West. I thought I had a really clear idea of what I was making out West, but now that I have some space from the work, I realize that the photos didn’t amount to any sort of discovery. After the crit, I was told to take a break from the West, and I did. I was told I needed to stay in Austin and make pictures for two months, which I didn’t want to hear at the time. That lasted for about a week after I got back from Berlin. I was trying to make pictures in Austin and I didn’t even want to live in Austin at the time, so it was difficult. I decided to go to Bastrop, which is about fifteen to twenty minutes south of Austin. It’s a little town that’s right next to this pretty special forest called the Lost Pines, which is considered a “pine island.”

It takes a very specific type of environment to grow these loblolly pines. There’s this archipelago of pine islands that eventually connect to the Piney Woods region of east Texas that spreads into Oklahoma and Arkansas and eventually connects with the Ozarks. The Lost Pines is the farthest west pine island in this archipelago. I was shooting there in this forest, a majority of which had burned down five years prior, so it was kind of this creepy setting and I met some people who were living there. I thought it was interesting that people were actually making a life in this place. I made work there for two months and I brought the pictures back to Hartford and it was really well-received. The critiques were short. They didn’t want to mess with what I was doing; they just wanted me to keep making more of it.

I was really restless going to the same forest roughly five or six times a week, so I started going to the other pine islands east of Texas, and finally said fuck it and drove to the Ozarks. I made it all the way there and I spent one week making pictures in the Ozarks. When I brought those pictures back, there was one photograph that I had made that made me feel that I should be there. That was the place.

Z: One might assume that the Ozarks are inhospitable to outsiders who show up taking pictures. Do you go into these trips with a great deal of trepidation or are you just sort of game?

MG: It’s not binary like that. I talk about this a lot with other people who work in a similar fashion that I do and there is never one surefire approach. It’s odd, when you’re traveling out West. It’s mostly just the open desert and you can see all your surroundings. You hop a fence, you see or hear a car coming from a mile away. Most of the time nobody gives a damn. Either it’s public land or it’s ranch land so big the owners would never know you’d stepped foot on their property. I think that I went into the Ozarks with that same approach. I guess that ignorance sort of helped me out in some ways. There were a few instances where I learned shit like that doesn’t fly in the Ozarks. It all depends. I just learned to adapt. My camera certainly helped. I shot with a view camera while I was making Jasper. A lot of people stopped me in the Ozarks when I was using it. They thought I was a land surveyor; they thought that I had surveying equipment. So either people left me alone or they asked me what the hell I was doing. It’s not immediately identifiable as a camera. If they do identify it as a camera, they ask, “Why the hell are you using this old-timey camera?”

The view camera is bizarre. It definitely lent a hand in opening doors to some of these worlds. Sometimes I would wake up in the morning to start working and it might take three or four hours before I make a picture, then somebody curious about the camera would inquire about what I was doing and I would end up with them the rest of the day, making pictures in their home.

Z: When I was in Marfa, you told me a story about a coyote carcass—and much more. Would you mind re-telling that story?

MG: I don’t think I’ve told that story since you were here. I don’t tell it to too many people.

2016 was a comically bad year. We had the terrible election. The break-up that I had started in 2015 ultimately ended in 2016. The whole trying-to-completely-redefine-my-voice-as-photographer thing happened. 2016 was a pretty awful year for me. I had stayed in a motel the night before New Year’s Eve. I woke up that morning, thinking it’s the very last day of this year, it’s been a terrible year, let’s just get out there and do your best, make some pictures.

It was really, really fucking cold that morning. I got dressed. I’m a creature of habit whenever I’m at home. I try to at least adapt, whenever I’m on the road, and have some sort of ritual. It’s little things like that that can keep you sane on the road. If I’m sleeping in the car or in a motel or camping somewhere, I always try to get a cup of coffee and a little bit of food at a gas station first thing in the morning.

I had made a habit of going to this gas station called Casey’s outside of Jasper in a town called Harrison. To give you an idea about Casey’s, one time a woman was buying pizza at 6 a.m. and I said to the cashier, “Damn, the pizza must be pretty good if folks are buying it this early.” He said, “She bought the breakfast pizza.” I asked what makes it a breakfast pizza, and he goes, “Sausage.” They had four different types of coffee and I’m thinking what kind I want to get today. I got a cup of coffee and a thing of almonds, and I got back in my car. I was trying to figure out what I should make a picture of that morning. It was still dark out. It was probably thirty minutes before sunrise. I remembered that in this town called Green Forest, kind of by Harrison, there was a dead coyote that was strung up onto some barbed wire. I had made a photograph of it before. He was pretty fresh when I first came across him, and it had been about a month, and I thought that if that coyote was still there he’s probably decayed a little, and that could be interesting.

I drove over and I parked my car and he was still there. I remember him being still pretty well-preserved, I’m guessing, because of the cold. Most of it was still strung up. This coyote was hanging near a road about four or five miles off the highway, just a little two-lane road. He was on the fence. He was up higher, then there was a ditch, then the road. But it was a really narrow shoulder. This wasn’t a very busy road—just some county road. My car is parked halfway in the ditch and halfway onto the shoulder, which is typical. I got out of my car, set up my view camera. I had made this photograph before. I knew exactly where I needed to stand. The sun was coming up. I don’t remember if my head was under the dark cloth or if I was fiddling with my camera, but I do remember hearing the gunshot.

I grew up hunting. I’ve been around guns, heard a million guns fire before. This one felt different because not only was it close, it sounded and felt how bullets sound in movies when they whiz by you. I immediately knew it was directed at me. I remember my instincts kicked in. I hugged onto my camera and went into that ditch. Two shots were fired again with the same whizzing effect. I felt like it was right over me. I remember yelling something to the tune of “I’m taking a fucking picture!” I remember crawling. I had my camera up against me and the legs of the tripod were dragging against me. I crawled around to the driver’s side of my car and pushed the camera in, then I got in the car really low and started the ignition and drove five or ten feet with my head ducked down. I drove a couple miles, pulled off the side of the road. I know I was in shock, because I can’t even remember if I sat in my truck for five minutes or an hour. I snapped out of it and just thought, “I have to make work. I have to make pictures.”

I drove into that town, Green Forest. I remember seeing this man walking into a house on the outskirts of Green Forest. Green Forest wasn’t really a big town. Usually if I see a stranger who I think would make a good picture, it takes me a little while to go ask them, to build up the courage. But it was so quick—He would make a good picture—then I found myself on the front porch knocking on the door. His name was Clay. Clay opens the front door. I introduced myself, told him what I was doing, and a woman walked up afterward. I could tell that Clay was not all there. Clay was an enormous Elvis fan. He had slicked hair, big mutton chops. He also had on an Elvis-type shirt, a pretty gross shirt. He told me his name was Clay. The woman who walked up, I told her what I was doing and she said, “Clay would love to have his picture taken, but everyone around here calls him Elvis.”

I remember going back to the car and getting my camera, coming back into the house, and the house was completely disgusting. There was old food, beer cans, and clothes laying everywhere. I remember Clay was telling me all about his life, and the woman went in the back. At some point before I had made a photograph, Clay was like, “We should watch 3000 Miles to Graceland,” which is not even a movie that has Elvis in it. It has Christian Slater and Kevin Costner. I said, “Yeah, let’s watch it.” We were watching it and someone came into the house, didn’t knock, didn’t introduce themselves, just walked straight through the living room where we were into the back, and after ten or fifteen minutes just left. Two or three people came in and did that exact same thing. At some point in there I made a picture, because there’s the picture in Jasper of the TV with the road on it—it’s from the movie we were watching.

Through all that, I realized that although I’ve never been around meth before, I had been told that meth smells like cat piss, and I realized, “Fuck, these people coming in here are buying meth. I’m in a meth house right now.” But for whatever reason, the radar didn’t go off that I should get out of there. We just kept watching the movie. Then I remember asking Clay about this picture on the wall of his brother. He started telling me about his brother, who had recently died, I believe, of a drug overdose, and Clay started crying when he was telling me about it. I asked him if he would mind if I made a portrait of him. He didn’t mind, but he also wasn’t all there. I don’t know if he was on meth or what his deal was. He was crying and I remember getting under the dark cloth. I remember it so vividly—this was the only clear part of that day—I remember being under the dark cloth and him looking at me through the lens of my camera and me looking through him and I remember thinking, “You’re a terrible human if you take this picture.” I got out from under the dark cloth, put the film holder in, took out the dark slide and clicked the shutter. And felt terrible about it. I never used the picture for anything.

Eventually I made my way out of there and the woman that was there followed me out to the car. I had twenty or thirty bucks on me and I gave it to her and wished her a Happy New Year. I took off and the day just seemed to have gone by. I remember thinking that for some reason I just needed to get a can of black-eyed peas on New Year’s Eve. For good luck, I guess. I went to this small grocery store and got one. I keep a can opener in my glove box. I was sitting in my car, watching the last sun of the year go down, and I opened the can and spilled the black-eyed peas all over myself. I didn’t even clean them up, I just drove back to the motel where I was staying, had a beer or two and called it a night. I was asleep by nine o’clock and slept into 2017.

Michael Juliani is a poet, editor, and writer from South Pasadena, California. His work has appeared in outlets such as NECK, Washington Square Review, Guernica, BOMB, and the L.A. Review of Books. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.