San Francisco’s most cherished holiday—that’s right, Halloween—is nearly upon us. That means it’s colder and darker outside before you know it, so what better excuse to curl up in bed with a (frightfully) good book? In keeping with the spirit of the season, we’ve assembled a list of recommended reads that might just help you keep warm, that is, if they don’t chill you to the bone.

San Francisco’s most cherished holiday—that’s right, Halloween—is nearly upon us. That means it’s colder and darker outside before you know it, so what better excuse to curl up in bed with a (frightfully) good book? In keeping with the spirit of the season, we’ve assembled a list of recommended reads that might just help you keep warm, that is, if they don’t chill you to the bone.

Laura Cogan, Editor: The dehumanizing violence of American racism and white power is the horror at the heart of Hari Kunzru’s novel, White Tears. I read it earlier this year, as a part of the Tournament of Books (where I offered commentary in the opening round), and though there were aspects that I wish had been developed more, the novel has stayed with me. It can be fascinating when the genre of horror is used incisively (either in film or narrative) to address social concerns. In this regard, Kunzru’s book is timely and memorable—both for its visceral evocation of the way we are haunted, whether we can perceive it and admit it or not, by slavery, and for its treatment of contemporary racism.

Laura Cogan, Editor: The dehumanizing violence of American racism and white power is the horror at the heart of Hari Kunzru’s novel, White Tears. I read it earlier this year, as a part of the Tournament of Books (where I offered commentary in the opening round), and though there were aspects that I wish had been developed more, the novel has stayed with me. It can be fascinating when the genre of horror is used incisively (either in film or narrative) to address social concerns. In this regard, Kunzru’s book is timely and memorable—both for its visceral evocation of the way we are haunted, whether we can perceive it and admit it or not, by slavery, and for its treatment of contemporary racism.

As I noted earlier this year, White Tears drives home a serious point about the present-day legacies of our shameful past by making use of the propulsive conventions of the horror genre. But the novel is especially impressive for its layered critique of white exploitation of black Americans in many guises over generations. Issues of ownership, possession, and obsession come up in several forms throughout the book—and interwoven with this motif is a suggested critique of capitalism itself.

Part of the horror evoked here has to do with being disenfranchised. Which is a condition, if we pause to really dwell on it, as essentially horrifying as any. As one of Kunzru’s characters observes: “When you are powerless, your belief or disbelief is irrelevant. No one gives a damn about what you believe. But if some reality believes in you, then you must live it. You can’t say no thank you. You can’t say I don’t want this. If horror believes in you, there’s nothing to be done.”

Peyton Harvey, Intern: After seeing the live production of X in London, I immediately purchased a ticket to see it again the following week. From the mind of Alistair McDowall comes a play that is exhilarating, mind-bending, and heartfelt. It’s the kind of story that you’ll want to revisit and absorb every detail that you may have missed. The stage production is magical, but the deftly crafted script is able to stand alone and conjures extremely visceral images in the mind of the reader.

Peyton Harvey, Intern: After seeing the live production of X in London, I immediately purchased a ticket to see it again the following week. From the mind of Alistair McDowall comes a play that is exhilarating, mind-bending, and heartfelt. It’s the kind of story that you’ll want to revisit and absorb every detail that you may have missed. The stage production is magical, but the deftly crafted script is able to stand alone and conjures extremely visceral images in the mind of the reader.

X, its the title befitting its enigmatic plot, serves as a measure of humanity and relationships through the lens of time. The play fuses elements of sci-fi, horror, and thriller; however, at its core it is a exploration of the human condition. We begin on a research station on Pluto with four astronauts: Gilda, Clark, Ray, and Cole. But soon the play’s timeline, like the minds of its characters, grows warped. The start of the play actually falls somewhere near the middle of the chronological narrative. The author presents clues to indicate where we are in the story: a watch only worn in certain scenes, the letter x written, apparently in blood, on the window.

The characters struggle to maintain their sanity as their memories begin to fade and merge together. In Act II, the in-house meteorologist Cole realizes that the station’s main clock and other means of keeping time have stopped working. As a result, none of the characters can tell how long they’ve been away from Earth, or even how many hours they’ve been awake.

Over time—whatever that word means to them now—they becomes increasingly less sure of who they are. McDowall adds an eerie levity to the plot as two characters play the game Guess Who, a game with definite questions and answers. Do I have blonde hair? Yes. Am I wearing a hat? No. Before long, the players lose their grip on their identities. Without any reference point to time back on Earth, they become more unstable.

While there are horrifying images of bloody letters sprawled on walls and the ghostly sound of a young girl’s voice, what proves most frightening is the slow realization that there is no escape from the characters’ increasing disconnect from reality.

X delves into the fragility of the human psyche. In one instance, Ray explains that he maintains his sanity by playing recordings of bird sounds: “I try to hold onto birds in particular.” Gilda, near breaking point, replies, “Hold onto X, X in particular.” The theme of holding on appears throughout the play. We are asked: who are we if we do not possess our own thoughts and memories? What do you hold onto when you are losing your very self?

M.M. Silva, Intern: The Alchemaster’s Apprentice by Walter Moers is one of my all-time favorites for many reasons. It takes its readers on a spooky adventure through a disease-ridden village called Zamonia ruled by an “alchemaster” named Goolion. It has the ability to either place you on the rough carpet of your fifth grade classroom, reading the coolest story of your youth or actually bring you into the story itself as the conflicted main character Echo. Echo is an ownerless “crat,” essentially a cat that can speak any language with a slightly different internal anatomy than other cats. This ends up putting Echo in a scary situation, as Goolion needs the fat of a crat for his own evil purposes.

M.M. Silva, Intern: The Alchemaster’s Apprentice by Walter Moers is one of my all-time favorites for many reasons. It takes its readers on a spooky adventure through a disease-ridden village called Zamonia ruled by an “alchemaster” named Goolion. It has the ability to either place you on the rough carpet of your fifth grade classroom, reading the coolest story of your youth or actually bring you into the story itself as the conflicted main character Echo. Echo is an ownerless “crat,” essentially a cat that can speak any language with a slightly different internal anatomy than other cats. This ends up putting Echo in a scary situation, as Goolion needs the fat of a crat for his own evil purposes.

It may sound like the the kind of imaginative fiction you’d read during childhood, but Moers’ novel is a perfect pick for Halloween and might add a little spice to your book list.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: “I think that what we all want is facts,” says Luke early on in Shirley Jackson’s classic 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House. “Something we can understand and put together.” Yet in Hill House, as in all great horror tales, “the facts” are exceedingly difficult to come by and increasingly irrelevant in the face of the world’s terror. As the story opens, Shirley Jackson introduces four characters to the imposing and architecturally irregular world of Hill House as a means to investigate just how precarious our notions of logic, self, and sanity can be. Following in the tradition of writers as venerable as Poe and Lovecraft, Jackson understood that the most terrible terrain fiction can navigate is not a fog-ridden graveyard or castle crypt, but the human mind. Her prose is so effective at capturing the anxiety-ridden interiority of her main character, Eleanor Vance, that it’s easy to imagine the strange noises and disturbances of Hill House as merely the product of mental illness. Many readers have noted Eleanor’s similarities to Jackson herself: both suffered under the thrall of a domineering mother and felt increasingly stifled by domestic life.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: “I think that what we all want is facts,” says Luke early on in Shirley Jackson’s classic 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House. “Something we can understand and put together.” Yet in Hill House, as in all great horror tales, “the facts” are exceedingly difficult to come by and increasingly irrelevant in the face of the world’s terror. As the story opens, Shirley Jackson introduces four characters to the imposing and architecturally irregular world of Hill House as a means to investigate just how precarious our notions of logic, self, and sanity can be. Following in the tradition of writers as venerable as Poe and Lovecraft, Jackson understood that the most terrible terrain fiction can navigate is not a fog-ridden graveyard or castle crypt, but the human mind. Her prose is so effective at capturing the anxiety-ridden interiority of her main character, Eleanor Vance, that it’s easy to imagine the strange noises and disturbances of Hill House as merely the product of mental illness. Many readers have noted Eleanor’s similarities to Jackson herself: both suffered under the thrall of a domineering mother and felt increasingly stifled by domestic life.

Of course, Jackson herself professed to critics that she did, indeed, believe in ghosts—and she writes The Haunting of Hill House with the conviction of a believer. “Fear is the relinquishment of logic, the willing relinquishing of reasonable patterns,” claims the measured and quite rational Doctor Montague, who has summoned these three strangers to Hill House. “We yield to it or we fight it, but we cannot meet it halfway.” But how to hold onto logic, how to fight fear at a scene like the one Jackson describes during Eleanor and Theodora’s nocturnal stroll of the Hill House grounds: “On either side of them the trees, silent, relinquished the dark color they had held, paled, grew transparent and stood white and ghastly against the black sky. The grass was colorless, the path wide and black; there was nothing else.” It’s difficult to imagine a better treat during the October season than to savor such a passage as Halloween draws near. But the pleasures of Jackson’s novel run deep—indeed, it’s actually quite hilarious at parts, particularly once Dr. Montague’s brash wife enters the scene—and there’s no need to shelve the book after the 31st. The Haunting’s closing chapters make it quite clear that, for Eleanor, the greatest horror might not be found in the slanted halls of Hill House, but in being forced to confront the overwhelming loneliness of her life as she prepares to depart. It’s this observation from Jackson that ensures the novel registers as insightful and even profound.

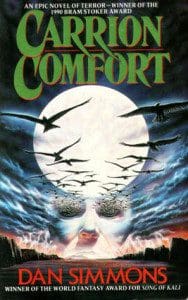

Bjorn Svendsen, Intern: Dan Simmons’ Carrion Comfort, released in 1989, is an epic 800-page horror novel which twists the traditional vampire mythos by featuring human monsters. Its title comes from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem about spiritual despair, but the novel is about “mind vampires”— human beings with the psychic talent to control others with only a glance. These mind vampires sustain themselves with the emotional energy of others while forcing them to do their bidding like human puppets. Simmons writes in the introduction: “Absolute power does more than corrupt us absolutely, it gives us the blood-power taste of total control. Such control is more addicting than heroin. It is the addiction of mind vampirism.”

Bjorn Svendsen, Intern: Dan Simmons’ Carrion Comfort, released in 1989, is an epic 800-page horror novel which twists the traditional vampire mythos by featuring human monsters. Its title comes from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem about spiritual despair, but the novel is about “mind vampires”— human beings with the psychic talent to control others with only a glance. These mind vampires sustain themselves with the emotional energy of others while forcing them to do their bidding like human puppets. Simmons writes in the introduction: “Absolute power does more than corrupt us absolutely, it gives us the blood-power taste of total control. Such control is more addicting than heroin. It is the addiction of mind vampirism.”

Carrion Comfort opens with a prologue. The protagonist, Saul Laski, is a Jewish man imprisoned in Chelmno extermination camp. There he encounters one of the novel’s perversely evil antagonists, an SS Colonel named Wilhelm von Borchert. Laski is forced into a game of human chess, where the people standing in for pieces are slaughtered when taken off the board. Laski survives the encounter and the war, and by the early eighties, has become a studied psychiatrist with a deep understanding of human violence. He has never forgotten his torture at the hands of a mind vampire, and devotes himself to understanding their rare and terrible talent, and ultimately, to destroying them. While Carrion Comfort is primarily a horror novel about facing adversity, it also balances elements of science fiction and the spy thriller. The novel features multiple characters, and the majority of the narrative is presented in third person. The first person is sparingly used for chapters featuring one of the novel’s main antagonists, exposing the workings of a psychopathic mind to chilling effect.

Carrion Comfort is a powerful meditation on corruption, violence, and the human will, and it is no surprise that it won the Bram Stoker Award the year of its publication. Stephen King has called Carrion Comfort, “One of the three greatest horror novels of the twentieth century.” Need I say more?