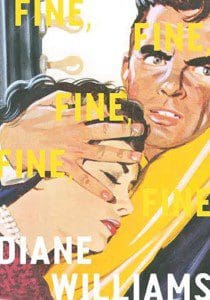

Diane Williams has remained on the edge of American experimental short fiction for the last twenty years. Known for her compact, oblique stories and her extraordinary use of non sequiturs, Williams has written seven books of stories and was an editor at StoryQuarterly before starting the NOON literary annual. She has been lauded by authors Jonathan Franzen, Sam Lipsyte, and Lydia Davis. And her latest book of remarkably potent short fiction, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine (136 pages; McSweeney’s), not only keeps her on the forefront of the form, but also redefines its parameters.

Diane Williams has remained on the edge of American experimental short fiction for the last twenty years. Known for her compact, oblique stories and her extraordinary use of non sequiturs, Williams has written seven books of stories and was an editor at StoryQuarterly before starting the NOON literary annual. She has been lauded by authors Jonathan Franzen, Sam Lipsyte, and Lydia Davis. And her latest book of remarkably potent short fiction, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine (136 pages; McSweeney’s), not only keeps her on the forefront of the form, but also redefines its parameters.

In an interview with HTMLGiant.com, Williams said: “The sentence cannot be overemphasized…neither can a fragment of a sentence or any syllable of a word. The writer either exploits the language for maximum effects or she does not.” For the forty stories in Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, this sentiment holds true: Williams renders every single word like a prism of implication, and she stretches the space between sentences as wide as chapter breaks, while the sentences themselves somehow read like stand-alone stories. The density of her writing warrants a closer reading than most fiction because it also reads like superb poetry, just casual and fluid and lilting between verse and improvised speech.

Above all, this collection expresses a viciously recursive self-awareness through its narrators and characters (including Williams herself, who shows up by name in at least four of these stories) who attempt to fulfill the stories they tell themselves.

The brevity of the stories, most of them only two pages long, entice the reader to chew through many in a row, as if plowing through chapters in a discontinuous novel. Yet the richness of each piece warrants a kind of re-rereading, where every time a new line is encountered the story needs to be restarted from the beginning. To categorize Diane Williams’ stories as simply flash fiction would be a disservice. In an interview with numerocinq.com, she balks at the idea of categorization of any kind, saying, “I have no special concern for brevity. … [And] I admit that the definition of a literary genre doesn’t interest me. Would anyone create a genre for small paintings?—and a special technical term for these? Language gathered into a composition is vivid and consequential or it isn’t.”

The influence of renowned editor Gordon Lish, who taught Williams in 1986 and also edited her book The Stupefaction, certainly shows in Williams’s minimalism. Likewise, the stories’ occasionally menacing undertones bring Raymond Carver to mind. But Williams remains within her own voice no matter how many perspectives she assumes. For example, in the story “When I Am Old and Ugly,” she takes on the mindset of an old woman writing a journal—embracing, embellishing, and, ultimately, making poetry out of her narrator’s untrained, informal voice: “I am unhappily married. Today I was dressed up in red-fox orange—orangutan orange—apricot orange, candlelight orange.”

Williams’s plots can be as straightforward as a solitary woman’s thoughts during a train ride, or as complex as a dinner party overshadowed by multiple infidelities. These are the stories of mundane moments, of the accumulated meanings of objects in people’s lives, of how habitual thoughts can at times be dramatically inescapable; these are stories of mothers and daughters, and those daughters’ daughters all haunting one another as they parallel and syncopate across fractured narratives.

Many of Williams’ characters are affluent and equal parts idealistic and insecure. As in the story “Of The True and Final Good,” where a woman, who is overcome suddenly with abstract fear while touring a mansion, is described as “carefully fashioned, vivid and polished, but should her desired result fail to be obtained—she’ll fade.” All of Williams’s characters strive so hard to achieve immaculate appearances and circumstances, when in fact they’re as malleable and fallible as anybody.

Writing that’s this focused ends up mirroring the writer, and Williams invites scrutiny upon herself; the above quote could just as easily be describing her authorial presence on the page. She questions the categories of fact and fiction just as subtly as she does the ideas of genre, with a line in almost every story that can turn the pieces into extended metafictional analogies.

Williams’ stories deliver an immense pressure; they’re emotionally and thematically ultra-dense, and the heat of that friction, of her style, melts down and mixes together narratives and characters in a short amount of space. Her new collection grapples with what a short story can and is “supposed” to be, and inevitably forces the reader to redefine where prose and poetry, and fact and fiction, begin and end. Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine would even suggest that life itself is an indeterminable mix of prose and poetry; that it’s often experienced in fleeting and confusing situations, where people bleed in and out of the subjective and objective lenses of their own selves, “reading” their lives as they “write” them, the two acts often becoming difficult to distinguish from one another.

Sounds extremely interesting, though I don’t know if I would so easily reject the idea of genres in literature, as Williams would like to. Genre based on relative “size” doesn’t really exist in paintings. However, I’m sure that general attitude of ‘de-genrefication’ makes for a very interesting read, as James has asserted.