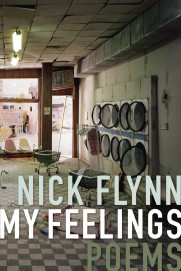

“Who / can tell me where I will fall next, where / the thorn will enter?” asks Nick Flynn in “Beads of Sweat,” a poem in his fourth poetry collection, My Feelings (Graywolf Press, 89 pages), which was released this summer. Placed early on in a six-part meditation on fatherhood, pain, and loss, the poem recalls the feeling of unknowability, the same feeling that even Moses encountered when he stared into the burning bush. “Up there he heard / a voice, When I speak you will know from where it comes / & you will turn into it.” Throughout My Feelings, Flynn seeks the root of this unspeakable void—the search is, all at once, a biblical, cyclical journey and an excruciating longing to turn into something beyond the human form. Flynn’s writing defies resolution but longs for communion. Each poem is asymptotic—always reaching and rising.

“Who / can tell me where I will fall next, where / the thorn will enter?” asks Nick Flynn in “Beads of Sweat,” a poem in his fourth poetry collection, My Feelings (Graywolf Press, 89 pages), which was released this summer. Placed early on in a six-part meditation on fatherhood, pain, and loss, the poem recalls the feeling of unknowability, the same feeling that even Moses encountered when he stared into the burning bush. “Up there he heard / a voice, When I speak you will know from where it comes / & you will turn into it.” Throughout My Feelings, Flynn seeks the root of this unspeakable void—the search is, all at once, a biblical, cyclical journey and an excruciating longing to turn into something beyond the human form. Flynn’s writing defies resolution but longs for communion. Each poem is asymptotic—always reaching and rising.

Flynn makes sense of pain and memory in terms of architecture—the internal and external house of the body, the buried coffin, the hierarchy of heaven and earth. Despite the maelstrom the title suggests, the collection is highly structured and orderly; Flynn turns over each stone with one finger, inspects what he finds with a keen eye. He steps from one association of memory to another, from “Polaroid” to “A Note on the Periodic Table” to “Philip Seymour Hoffman.”

Despite these careful investigations, the search for the tangible location of pain also demonstrates the disorientation caused by trauma. In “AK-47” he writes, “this house…when you go back, if you go back, / if you can find your way, it won’t, it cannot…be as you remember…this house you grew out of you grew up inside it.” Even as Flynn names his old house as a physical site of nostalgia and loss, the place dissolves into illusion, into the abstract. Architecture, then, represents an upward momentum—the building being built, the “building blocks” of the periodic table—but also a weighted structure that will collapse and bury. The question of the collection then is what kind of structure will Flynn choose: one that rises or buries? In “Cathedral of Salt,” he offers a possible answer: “Beneath all this I’m carving a cathedral / of salt,” he writes, “I keep / the entrance hidden, no one seems to notice / the hours I’m missing…”

This willingness to bury and be buried pulls from the speaker’s present life: the recent death of an estranged father, the difficulty of navigating fatherhood, and the strain of relationships. Each of these moments invariably connect to the suicide of Flynn’s mother, a loss that haunts each line in the collection. In “The When & the How,” Flynn ties this event with a litany of italicized torments:

I asked about your family—you

(like me) had yet to mention any desperate distant

tethered

& as the question left my mouth I knew

confusing tongue-tied the instant before you

spoke it incomprehensible wayworn insubstantial

the moment I conjured her shadowy mystical

elemental

by uttering the word MOTHER fucked-up

painful wounded invisible unspeakable meaningless

I knew yours (like mine) had killed herself delicate & that

desperate unknown our conversations

from that moment on would be simply broken

limited backwoods

a matter of the how flimsy shameful crushing

& the when

Here, the mother is conjured from the commotion of the mind. Later, in the title poem, we learn that each of the italicized words is an adjective describing Flynn’s feelings. He lists each word in succession—“my…desperate flimsy shameful crushing guarded”—and ends the poem abruptly—“feelings.” The adjectives, physically crossed out on the page, signify a self-deprecating erasure of one’s self-worth. It is a denial of pain while acknowledging both how impossible it is to deny pain and our need for others to recognize that pain. Yet these words also bind “the word MOTHER” to the overwhelming, inexplicable emotion pulsing throughout these poems, from Moses’ dread to the death of Flynn’s father. In “My Triggers,” Flynn writes, “Her mother hadn’t left a note, mine had written / I FEEL TOO MUCH in hers, as if these unnamed / feelings… could destroy her (they did).” Flynn’s feelings must be struck through perhaps because they are not wholly his—they are a repetition of his mother’s grief, an overflow of her feelings into his. In “If This Is Your Final Destination,” Flynn writes about the mornings he spent at the supermarket lunch counter with his mother. It’s a haunting conflation of maternal memory and fatherhood as his mother’s life bleeds strangely into his:

I’d twirl or

wander or make toast, contemplating the basket

of butter & jelly, each in its little wasteful tub,

impervious to air or time or decay. Angel of Grape,

your purple body not only filled those coffins

but took the shape of those coffins—emptiness made

whole, color now a shape. Angel, my daughter now

wants only you, she asks for the whole basket, she

pulls back each sheet, puts her tongue in—

strawberry is her favorite, because it tastes

like strawberry.

My Feelings becomes an investigation of not only Flynn’s feelings but of a wide canon of female sadness and pain, a canon occupied by women—Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, Anne Sexton—who felt “too much.” In “When I Was A Girl” he embodies the impossible danger and delicacy the female form contains. He writes, “In the beginning I was / a girl…If a bird landed in my palm / I could either crush it / or set it free.” In “Aquarium” he invokes the biblical Mary; in “Beads of Sweat,” the fall of Adam and Eve. Each of these poems longs, achingly and beautifully, for communion with something beyond us, whether a God or the afterlife. However, by titling his collection My Feelings and writing himself into this female lineage, Flynn treads on sensitive ground—female writers have consistently been criticized for over-emotionality, for being too confessional or melancholic. Here, Flynn runs the risk of erasure, though he acknowledges the possibility of appropriation. On the book’s copyright page, he notes: “Disclaimer: The word ‘my’ in the title is meant to signify the author—as such no claims are made on anyone else’s.”

While pain disorients in the first half of the collection, Flynn’s mother acts as a guiding compass toward the end. In “The Incomprehensibility,” Flynn brings us to the source of his emotion, imagining “the very moment my mother / will press a bullet into the chamber of her .38.” He then describes Fra Angelico’s Annunciation, how the Angel, hand outstretched, has yet to touch Mary’s shoulder. My Feelings hangs on the precipice of the “what if?”—the moment before the irrevocable: before the bullet enters, before the annunciation, when, as Flynn writes, “It’s still not too late to turn back.” “The Incomprehensibility” confirms the devastating reality that certain traumas cannot be overcome. Yet this realization leads to understanding and orientation instead of despair. (In the poem, his mother, circling in an airplane, offers a way to see through the clouds: “Poke a hole through the heavy curtains, she / mouths—you’ll see they are not even real.”)

Flynn’s writing resists conclusion, yet in the last few poems of My Feelings a quiet acceptance can be detected—pills are washed down the toilet, burnt pages are glued “into a clean white book,” and the speaker looks out from his underground home to lighted streets. In “The Washing of the Body,” a corpse is being turned and touched by the speaker’s hands:

one whispers Sweetie,

we’re going to roll you over now

your back

still warm where the blood pools

We find that the unknowable void contains, perhaps, not terror but warmth: it’s a place where the blood pools. Here, the physical disappears and we are left with something rising—out of the body.