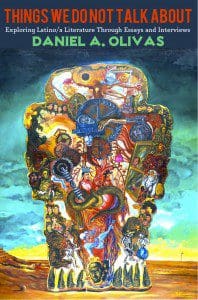

“Write what you know” is a common phrase in the writing world. Daniel A Olivas’s new book, Things We Do Not Talk About: Exploring Latino/a Literature Through Essays and Interviews (202 pages; San Diego State University Press), raises and discusses questions with himself and other authors about what it means to be a Latino writer and how that may (or may not) influences their writings. Olivas, the author of seven books (The Book of Want, Latinos in Lotusland), doesn’t claim, though, that this collection of various Latino authors’ ideas and thoughts on their cultural lineages and their work (as captured in Olivas’s previously published essays and interviews) has all the answers.

“Write what you know” is a common phrase in the writing world. Daniel A Olivas’s new book, Things We Do Not Talk About: Exploring Latino/a Literature Through Essays and Interviews (202 pages; San Diego State University Press), raises and discusses questions with himself and other authors about what it means to be a Latino writer and how that may (or may not) influences their writings. Olivas, the author of seven books (The Book of Want, Latinos in Lotusland), doesn’t claim, though, that this collection of various Latino authors’ ideas and thoughts on their cultural lineages and their work (as captured in Olivas’s previously published essays and interviews) has all the answers.

The book is divided into Olivas’s essays and interviews. The essays are snippets of the author’s life, ranging from “The Priest Who Preyed,” which focuses on how the revelation of molesting priests affected the mostly Catholic Latino community, to “Great Expectations,” an essay on what’s it’s like for him to try and sell his books at an event and the small joys that come despite the (lack of) crowds and buyers. Olivas’s tone remains light throughout; instead of imposing his thoughts on the Latino community, he poses questions to think about openly.

The book’s second section is made up of brief interviews Olivas conducted between 2005 and 2012 with other Latino writers, including Daniel Alarcón, Sandra Cisneros, Héctor Tobar, Justin Torres, and Carlos E. Cortés. In these interviews—ranging in length from a page-and-a-half to seven—the writers tell their own stories as to why they write. For most of them, their cultural background fuels their work: they write what they know in the hopes of sharing their experiences with others, Latino and non-Latino alike. These acclaimed writers acknowledge their mistakes (Alarcón talk about his first semester teaching), that they can take a really long time to complete books, and that they change their minds. (Olivas mentions in the introduction that upon reviewing the interviews, many of the authors were embarrassed by their responses to his queries.)

The big question that arises from Things We Do Not Talk About is what exactly does it mean to be a Latino writer? Is it merely a writer who happens to be born Latino? Or does it go beyond that? Does it specifically mean a writer of that heritage who presents the culture in his or her writing? Novelist Salvador Plascencia states in his interview that he didn’t want to “forefront his ethnicity over his writing” when he went with McSweeney’s, as opposed to a Latino imprint, as the publisher of The People of Paper. Given that writers should be able to publish and write whatever they want, are they nonetheless obliged to address their cultural identity? And if they don’t, does that exclude them from being considered a Latino writer?

These identity questions discussed by Olivas and his subjects are universal, as are the other aspects of the writing life covered here— from the contentment of knowing people are somewhere out there reading your work to the hardships of trying to write around your everyday life. (Olivas is also a lawyer, a father, and husband; his writer career is his “second act.”) The drive of these writers to express their experience is what pushes them.