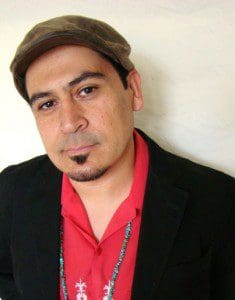

Who was the woman known to history only as “Terry, The Mexican Girl” from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road? Given that she was the linchpin for what became one of the most renowned tales in American letters, and that virtually all of Kerouac’s characters were based on real people who subsequently became famous themselves by association with the book and, often, as artists in their own right, it seemed improbable that no one had taken the time to track her down. That is, until author, poet and performer Tim Z. Hernandez found himself standing on the front doorstep of the house of a 92 year-old woman named Bea Franco.

Just months prior to her death, she had no knowledge of her place in literary history. But, had it not been for the diminutive daughter of migrant farm workers from California’s San Joaquin Valley, the world may never have heard of a vagabond scribbler named Kerouac and the book that defined a generation and launched 100,000 road trips may never have made it to print.

For years Kerouac had shopped around the manuscript for On the Road, but it wasn’t until the Paris Review published the excerpt about “The Mexican Girl” in 1955 that he gained notice and, finally, a publisher. This key detail did not escape Hernandez and he spent the several years researching Kerouac and the period in which On the Road was published. He pored over Kerouac’s correspondence in the archives of the New York Public Library and it was there he found the tender letters Bea had written to “Jackie.”

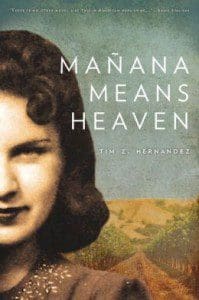

The story Hernandez tells in his historical novel, Mañana Means Heaven (University of Arizona Press; 240 pages), and the story behind his labor to find Bea and bring her story to the page, seems at once incredible and inevitable. Had Jack and Bea not caught the same bus in Selma, California, On the Road may never have found its place in the canon. Had Hernandez not latched onto the notion of telling the tale of “The Mexican Girl,” he would never have sought her out and found her living just one mile from his own home in California, and she would never have known of the import of her place in literary history. Her role as the central character in Mañana Means Heaven at last gives Bea an identity and a voice beyond Kerouac’s brief account. Hernandez’s portrayal offers a telling counterpoint to Kerouac’s rendering, reclaiming her agency and offering a depth and insight into her circumstances and the life of women like her who, both on the page and in everyday life, are too often consigned to anonymity.

Hernandez is currently on a book tour in support of Mañana Means Heaven. (For those interested in learning more about his research and the interviews behind the book, visit his thoughtful and wonderfully written website and blog.) The following Q&A was conducted via email.

ZYZZYVA: You pursued the idea that led to you to write Mañana Means Heaven on and off for several years. What was the impulse that made you feel, “This is a story that must be told and I will be the one who tells it?”

ZYZZYVA: You pursued the idea that led to you to write Mañana Means Heaven on and off for several years. What was the impulse that made you feel, “This is a story that must be told and I will be the one who tells it?”

Tim Z. Hernandez: The impulse came to me in one moment of awareness where I found myself standing in the dead center of an intersection. In 2007 I walked out of a classroom at Naropa University, the Jack Kerouac School, where we had been discussing Beat lineage. I left the discussion thinking quite a bit about the long list of Chican@ writers I had imagined myself more aligned with; Victor Martinez, Juan Felipe Herrera, etc. At that moment I had a copy of On the Road with me and when I opened it up to the section about “Terry, the Mexican Girl” it leapt out at me like it hadn’t before. Too, the fact that I was from the same territory that “Terry” was from, California’s San Joaquin Valley, and being the son and grandson of migrant farm workers, I knew I could shed light on this specific character in a way that would contribute to the conversation—the larger conversation of the Beats, lineage, and Latinos—but also to the conversation I just had in the classroom. Also, I’ve always believed that when a door of this caliber opens to you, it’s becomes your responsibility to walk on through.

Z: There were a number of ways you could have approached Bea Franco as a subject. Given the level of research you conducted and the amount of time you spent interviewing her—and simply visiting with her and her family—this could have been non-fiction. A biography, an article, a profile, etc. What was it about her story that led you to address it through historical fiction? Do you feel that allowed you more latitude to fully realize her story?

TZH: In my early research I quickly became aware that there were several books written by former wives or lovers of Kerouac’s, all of which were memoirs or biographies, or some other non-fictional approach. I wanted Bea’s story to stand apart from all of those, but mostly I wanted it to be a direct response to Kerouac’s version of events in On the Road. I wanted Bea’s story to work on the same “playing field,” and utilize the same “set of rules,” in some cases directly, and other cases intentionally turning the rules, thoughts or perspectives on their head. Also, the interviews I did with Bea Franco herself presented some surprising challenges, which I felt could only be resolved with fiction. But in the end, as I said to Bea directly, “Even though this book is labeled fiction, it is still closer to the truth about who you are than anything out there that is sitting on shelves labeled non-fiction.”

Z: You spent a significant amount of time attempting to live in her mind and inhabit her world during the 15 days she spent with Kerouac. You came to understand her in a way few people beyond actors and writers ever care to. With the exception of Kerouac, you are perhaps the only other person in her life who spent time thinking about her in that specific, intimate way. Your interest in her was much like his: he wanted to hear her story, see things through her eyes. How do you imagine your impressions of her were different from those of Kerouac’s? How were they similar?

TZH: Yes, well, Kerouac actually pitched me a sweet lob ball in On the Road, when he wrote the line, “And we settled down to telling our stories. Her story was this:” And then he goes on to summarize her “story” in only three sentences. This is the very gap where my book resides. So, although he may have wanted to “hear” her story, he wasn’t interested so much in telling it—only in telling his experience of her. And this is what we get in On the Road, Sal Paradise’s take on “Terry.” In my interviews with Bea, I was less interested in asking “What do you remember of Jack?” and more interested in “Tell me who you are Bea? How did you grow up? Who did you love?”

Z: Bea passed away on August 15. There is a photo of her hands holding your book taken just one week before she died. What do you hope her reaction was to having the book in her hands? How do you imagine she actually felt?

TZH: Her daughter phoned me on the day the photo was taken, and told me that Bea was very happy with it. But mostly, that she loved the photo we decided to use for the cover. Bea was a petite woman with a lot of fire, according to family and friends I interviewed. But she was also a romantic, which comes through in her letters. Not just her letters to Kerouac, but letters she wrote to her second husband as well. She told me several times, in response to the idea of having a book written about her, “I didn’t do nothing so special, why me?” But she always had this coy look about her, like she knew exactly why her. Based on our talks, I’d like to imagine she was happy with the book in the end, although I didn’t get to her ask that directly. I was scheduled to visit her, to celebrate the book with her and her family, only a week after the day she passed. Almost three years after I first met her, and after all the talk of this book, she stuck around just long enough to finally see it manifest. And thank God her daughter Patricia was there to snap a photo of that moment with her cell phone, otherwise there’d be no image in existence of the “Mexican Girl” holding a copy of her book.

Z: During the same time that you were working in earnest on Mañana Means Heaven you were also pursuing a project to identify, and build a memorial to, the 28 workers who died in the Los Gatos Canyon plane crash memorialized in Woody Guthrie’s song “Deportee.” It seems that the two projects are fundamentally similar. Kerouac’s career was launched by “The Mexican Girl” and Guthrie’s protest anthem inspired greater attention to migrant workers and immigrants in general. Yet the real people who inspired these works were lost to history.

TZH: Yes, they are sister projects in my mind. Research on Mañana Means Heaven is what led me to the discovery of the plane crash story. In fact, I had written a whole chapter in MMH where Bea ponders the crash, but in the end that chapter was cut out. With both of these projects, I didn’t set out with any intentions to find the real people behind these key historical moments. The initial inspiration was to fictionalize a story, but then one door led to another, and then another, and then suddenly I found myself with information and documents that I knew were of historical significance, and that these were materials no one else had. With this realization also came a responsibility. Having lived in that part of the world—the San Joaquin Valley—all my life and having worked with dozens of community organizations, historical societies, schools, librarians, etc., I knew I had all the resources I needed in order to shed some light on these two stories. And of course, as an author my mission has always been to coax these kinds of stories out of obscurity.

Z: What was the most challenging aspect of putting together the book?

TZH: The most challenging aspect was in trying to strike the right balance between Bea’s story and the story of my search for her. The book is ultimately Bea’s story, but because she’s been the most elusive and mysterious character in On the Road, I knew that the telling of how I came to find her was also important to the overall context, and to proving that this was in fact the Bea Franco. Simultaneous to the writing of the book, I also wrote about 100 pages of non-fiction about my search—notes, journals, emails, transcriptions, meditations—as part of the process. There were so many challenges with this book, and depending on the day you caught me, I was either elated about it, or else I wanted to throw myself off a cliff. But maintaining this process of non-fiction writing alongside the fiction was entirely critical in helping me to keep my thoughts and ideas together.

Z: What aspect of Bea and her story do you most hope readers will take away from Mañana Means Heaven?

TZH: I asked Bea that same question once. “Bea, what do you want people to take away when they read your story?” She replied, “That I was mostly a good mother.” As for me, I hope readers will take away a good story, and leave with the idea that all around us, among the people who populate our daily lives, we are each made up of rich and epic stories. The stuff of great books. We need only ask each other, “What’s your story?”