Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique is one of the great examples of program music, which means notes, not words, are the storytellers. The story here is a lurid one of opium induced reveries and unrequited love that descends into murder, execution, and hell. I heard it for the first time in junior high school, back when music appreciation was considered a part of a public school’s core curriculum and stories of opium and sin didn’t trigger over-protective hysteria in the PTA. The work became the first piece of classical music I could recognize, despite the fact that music of all kinds (but not Symphonie Fantastique) was ubiquitous in my house growing up. I haven’t heard the work since my son studied it at his own school over ten years ago, nor did I listen to it very much in the many years prior. Still, I can easily hum the piece’s major theme—its idée fixe—recall its unusual instrumentation, and tell the story.

I’ll never know if the music, without the narrative, would have been as compelling. Having heard the tale and been shown in the score where certain events are “told,” I cannot separate the music of Symphonie Fantastique from images of the warped waltz, the walk to the scaffold, or the Witch’s Sabbath. When you attach words to music it is magnified in the same ways pictures enrich words. But I’ve often read books where my image of a main character doesn’t match the one the graphic designer decided to put on the cover. Can branding a piece of music with a story be equally limiting?

Abstract music does not tell a story but that doesn’t mean it can’t contribute toward an inner narrative. As a former flutist, playing was an alternative form for me of speaking a feeling or relating a sensation. When I was in college, I played in the orchestra that accompanied a performance of Bach’s great choral work, his St. Matthew Passion. The work includes a beautiful duet between flute and the alto soloist. We were performing in a gothic cathedral whose gloominess had settled over me like a shroud. The vocalist was my voice teacher who had no fondness for me nor I for her. Yet by the end of the duet, I had become the music and, in becoming the music, had no defense against anything that might harm me. Music leaves me vulnerable.

My musical library is filled with minor-keyed works with oboes that weep, violins that plead, and cellos that intone their loneliness; with chords that pile one atop the other, lush tones the color of burgundy, dissonance with resolution that comes a few beats too late. The closest I have ever come to being emotionally detached from a piece of music is while listening to Bach’s Goldberg Variations. In my Form and Analysis class in college I could find a great deal to appreciate in the Variations, but my ear, separated from my intellect, likens the work to the performance of a dressage horse whose perfect mincing prance seems a distant cousin of the cantering and leaping hunters and jumpers.

Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings has always been the work I’ve turned to in times of melancholia and sorrow, when I needed to be “teared” the way people were once bled. The music weeps; the notes appear as if they struggle to resonate. They step forward, climb, retreat, tempt you with a moment of resolution, but grief returns. The piece reaches its climax in a long high shimmering note. It could be a scream, an appeal, or a revelation. And then we are brought back down to a more private sorrow. What did I think while I listened to the Adagio? Sometimes I searched my mother’s life for clues to her own sorrows. When my children were babies, I grieved for the innocence that they didn’t know they would someday lose. Other times, the music brought me to my feet and I would dance because it was the closest I could come to riding the musical phrases.

Then I read that Barber wrote the Adagio for Strings as an elegy for men returning from war. It was Pat Barker’s book Regeneration or Geraldine Brooks’ March in musical form. While not a narrative, the work now had a theme, and I allowed the music to carry me into the grief and horror of battle and returning home forever changed. I later learned that Barber did not have this vision in mind. It was too late; my reveries had been altered. I had become sympathetic to others, but each time I tried to search inside myself I couldn’t escape the image of those soldiers. The intensity of the music had been increased, like sunlight through a magnifying glass, but its breadth of potential impact decreased.

Since February, I have been touring with my book, Motherhood Exaggerated, reading to friends and strangers about being a mother during my daughter’s treatment for cancer. I’ve read about the day her jaw cracked, her first MRI, her chemo, her hair loss (actually a funny scene), her surgery, her post-traumatic stress. I’ve recounted my history of anxiety, the death of my mother, the middle of the night isolation when my only company was Nadia’s pain. At each reading there is always someone who tells me I am so brave to tell this story out loud. But the book, which I hold at chest height, is my shield. It is telling the story. I am reading, not reliving. That barrier fell when I paired selected sections of my book with music that punctuated and elaborated on the meaning of the words.

Since February, I have been touring with my book, Motherhood Exaggerated, reading to friends and strangers about being a mother during my daughter’s treatment for cancer. I’ve read about the day her jaw cracked, her first MRI, her chemo, her hair loss (actually a funny scene), her surgery, her post-traumatic stress. I’ve recounted my history of anxiety, the death of my mother, the middle of the night isolation when my only company was Nadia’s pain. At each reading there is always someone who tells me I am so brave to tell this story out loud. But the book, which I hold at chest height, is my shield. It is telling the story. I am reading, not reliving. That barrier fell when I paired selected sections of my book with music that punctuated and elaborated on the meaning of the words.

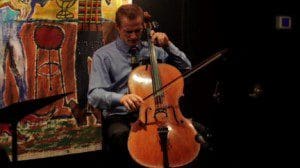

The Kodály Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8, is the musical representation of what happens when trauma strikes. At least that was my response the first time I heard it. Its abstractness had already been contaminated for me because I was listening to it with my story in mind. I heard the ways the music keeps you off balance, how its phrasings and rhythms throb; it is percussive and it sighs. The musician must dig deeply into the cello as if pulling the music out of the instrument rather than imposing the notes upon it. Even the bottom two strings are tuned differently, a symbol for me of the altered states I would be reading about. But Kodály is known for his use of Hungarian folk song and local musical idioms. When I first met Sebastian Bäverstam, the cellist I would be performing with, he referred to the piece’s whimsy. This made me think of music that would accompany a wild carnival ride rather than an MRI; both are scary but only one can take you into darkness.

The Kodály Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8, is the musical representation of what happens when trauma strikes. At least that was my response the first time I heard it. Its abstractness had already been contaminated for me because I was listening to it with my story in mind. I heard the ways the music keeps you off balance, how its phrasings and rhythms throb; it is percussive and it sighs. The musician must dig deeply into the cello as if pulling the music out of the instrument rather than imposing the notes upon it. Even the bottom two strings are tuned differently, a symbol for me of the altered states I would be reading about. But Kodály is known for his use of Hungarian folk song and local musical idioms. When I first met Sebastian Bäverstam, the cellist I would be performing with, he referred to the piece’s whimsy. This made me think of music that would accompany a wild carnival ride rather than an MRI; both are scary but only one can take you into darkness.

The program Sebastian and I designed opens with the allegory that begins the book. While I was pregnant with Nadia and her twin brother, there was a third embryo that the doctor said wouldn’t survive. The allegory imagines Nadia absorbing that embryo’s soul into her own, but the soul becomes greedy and tries to take over Nadia’s body until Nadia’s jaw cracks and the soul—the tumor—is exposed. I rarely read this brief section but it seemed an ideal introduction to Kodály’s opening phrase—strident, slightly broken chords, notes that race through the registers searching for a place to be safe the way I had envisioned that third soul.

I had never thought about that soul, even when writing the allegory. I didn’t really believe that embryo ever had one. But entering the music, I wasn’t so sure. Perhaps I should have mourned it. It was in the midst of these thoughts that the sonata’s first movement ended. I wasn’t sure if I could rise, never mind read, as the past pasted itself onto the present.

The next section told of the anxiety disorders I suffered in college which caused physical distortions of my reality: The shower was the worst. When I closed my eyes to rinse my hair, my little stall became a flight simulator mimicking a ride through a thunderstorm. It rocked and pitched. I couldn’t tell up from down. So I sat down, pressed my buttocks and the backs of my legs against the cool floor tiles. I wedged my shoulders into the corner. I kept my hand on the wall. In this way I remained oriented.

From here, I re-entered the warped world I was first sucked into the day Nadia was diagnosed with cancer: As I walk Nadia into the room for the MRI …, see the cylinder, feel the claustrophobia, anticipate the noise of the machine, realize the likely news this test will deliver, I feel those long-dormant anxieties limping alongside me like a phantom limb.

When Sebastian began the sonata’s second movement, with its walking cadences, my phantom limb felt more real than ghostly. It stayed with me as the music ended, and I began to read. And I felt its presence as I came to the end, imagining myself in an MRI tube and confronting the fear that I would be unable to care for Nadia since I had never experienced what she would be going through.

And then Sebastian launched into the final movement. This is where the whimsy that Sebastian originally spoke of is most obvious. Initially, I wanted to exclude this movement; it seemed too celebratory. It made me want to tap my toes. Perhaps it would be best to pair this movement with a section at the end of the book which shows Nadia as the beautiful twenty-year-old dancer she has become. But disorientation is never far away in this sonata. The downbeat disappears. Slippery scales, sudden chords strummed like a guitar, and hectic oscillating between strings brought me right back into that MRI room. I closed my eyes to remove any distraction that might interfere with the work of my ears. But because the cellist must employ every technique at his disposal to play this piece, the performance of it becomes physically compelling. I couldn’t ignore Sebastian’s inhales, shifts, the flow of the bow, the arch and dance of his fingers. The music was causing a physical representation of what I wanted my words to project—that I too had to employ every technique at my disposal to care for my daughter.

What ultimately absorbed my attention was the bow. To draw the music out, it had to sacrifice a piece of itself as hair after hair snapped with the effort. It was literally pulling its hair out. During the applause I took the frayed bow from Sebastian and held it up to the audience. I wanted everyone to see in the bow a representation of Sebastian’s brilliance. I hadn’t yet recognized the true reason behind my fascination with that stick and its threads. Twelve years earlier, I was that bow, drawing and scraping myself across the strings of my daughter’s illness.

Sebastian and I have performed our program twice. At the end of the first one, a member of the audience said to me, “I bet Sebastian will never play that piece the same way again.” I saw this as a positive outcome; Sebastian, a young man who had never experienced what I was reading about, now had his view expanded and he could bring this new depth to his music.

After the second performance, I wasn’t as sure. In response to a question from the audience, Sebastian spoke about how he would think about the dizziness I experienced while he was playing a particular section and try to interpret that musically. I wondered if now Sebastian would always associate that section with the rockiness of my world. What could be cemented into his thinking after the third performance, the fourth?

Sebastian and I made a story from notes that didn’t know how much they had to say. But, unlike words, notes can tell more than one story. Also within the Kodály is the story of my son Max providing clownish accompaniment to a magic show in the hospital, and of Nadia gathering the hair she had gleefully removed from her head and leaving me a bowl of “angel hair pasta” at dinnertime. It could tell other scenes from the book—me and my father in his woodworking shop, or the serpentine dance steps I did with my mother, our arms wrapped around each other’s waists.

Sebastian and I have been thinking about creating a new program, with different music and different words. Maybe a more interesting exercise for us as artists, though, would be to alter only one variable—changing just the words and not the music or vice versa. Kodály and Barber and all composers can tell many stories. All I have to do is shift the angle of my reading glasses.

Judith Hannan has written for Opera News, the Huffington Post, and Woman’s Day, among other publications, and is the author of the memoir Motherhood Exaggerated (CavanKerry Press).

One thought on “Reading Music”