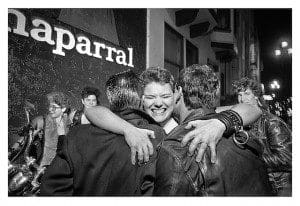

From 1985 to 1988, photographer Thomas Alleman worked in a jimmy-rigged laundryroom-cum-darkroom to document the life, passion, and spirit of one of the most prominent and historic gay neighborhoods in the world—San Francisco’s Castro District—in the face of AIDS. His latest show, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws: Gay San Francisco, 1985-1988,” runs at the Jewett Gallery in the San Francisco Main Library from December 1 though February 10. His photographs—stirring, necessary, and often deeply joyous—depict a brave set of San Franciscans propelled by a spirit that was unable to “be extinguished by something as dispassionate as a plague.” We spoke with the Los Angeles photographer over email about his work and his mission as a young photographer “accidentally” working in the midst of a growing crisis.

ZYZZYVA: Did you have a clear intention in your photographic approach during a time of real fear, silence, urgency, and stigma?

Thomas Alleman: Yes, I did have a clear intention. But it was more a pictorial, purely photographic intention, rather than an anthropological, historic ambition. I was well aware that we were experiencing a crisis of historic proportions, which would be remembered and lamented and studied for years to come, and that “ground zero” was the very community I was accidentally working in. A community, by the way, where a misunderstood, often reviled “sub-culture” had previously bloomed and thrived. So, any photographs anyone made under those circumstances were, and are, bound to be historically valuable and anthropologically revealing; I knew that, and that freed me from having to second-guess future historians. I lived in that culture because all my dearest friends did, and I photographed the events that my editors—who had a deeply nuanced understanding of what drove that culture—suggested I photograph. Given all that, I knew that my own mission was simply to photograph what was right under my nose, in a way that unconditionally reflected my personal vision, and then let history sort things out later.

Z: The title to your collection, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws,” hints at a vitality present in San Francisco’s gay community, even in the face of a terrible threat. As a photographer, how did you seek this liveliness out?

TA: Hopefully, it does more than hint. The Castro had been an incredibly vital place in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, perhaps as Harlem had been during it’s famous “Renaissance” in the ‘20s. A group of people who for countless years had been marginalized, cast-out, even hated, came together to live in a neighborhood where they built their own very vibrant culture. Because of San Francisco’s legendary openness and “tolerance”—which was often real, and sometimes an illusion—they were pretty much left to live in peace; because of their advantages in education and numbers, and driven by ambition and anger, they carved out a political presence that couldn’t be ignored, and which furthered their security and allowed the culture to flower even more fearlessly.

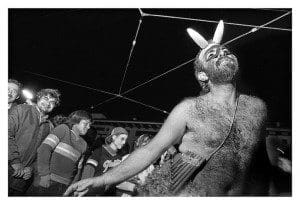

People who’d lived through those years—and folks who came to the Castro in the ‘80s to join the party—didn’t forget the joy and promise of all that. They were still the same beautiful, brilliant, lovers-of-life that they’d always been. But many of them died, and others were heartbroken and horrified and very afraid, and that does take a toll on the spirit of any tribe. Still, that “liveliness”—that passion—was so essential, so much a part of the community that it just couldn’t be extinguished by something as dispassionate as a plague. So, while many of the pictures in this show demonstrate a community in lamentation, many others are about anger and resolve, and most are about love and life. And disco and drag.

Z: Why do you feel it’s important to print these 53 photos so large?

TA: They’re certainly larger than anything I’ve done before, but, by most current standards, they’re fairly standard in size. In this age of digital reproduction, even a budget Epson makes prints that are bigger than what the Museum of Modern Art was showing just a generation ago. These days, pictures on walls are just damned big—and if they’re not, the question from the viewer or critic becomes, “Why do you feel it’s important to print these pictures so small?”

Z: Can you talk a little about your technical process at the time? Where did you develop these photographs?

TA: At the time, I was living with three other people in a third-floor walk-up in the Mission District. … I wheedled use of the laundry room, which I made vaguely light-tight with curtains of black felt and miles of duct tape. Still, when I printed during broad daylight, a kind of mist of white light oozed into the room, fogging my prints a little bit—which might account for the development of the high-contrast printing style in those days: my hard black and whites were fighting off the deadening effects of that chronic grayness. But when I printed at night—and there were a great many midnight sessions over the three years I used that darkroom—I could actually roll the curtains up and open the back door, because we were up above all the streetlights. Which was a really beautiful experience: I finally had some ventilation, and I could always look up from my work to watch the fog rolling in over Twin Peaks…

Z: What was the process of revisiting these photos like some twenty-four years later?

TA: It was a long, very revealing process. In real time, back in the ‘80s, I was pretty cavalier about my negatives when I was finished with their immediate use: I sleeved some, like you’re supposed to, and hung most of the rest on two or three nails I pounded into the wall next to the enlarger. When the nails got full, and negs began to slither onto the floor, I threw that whole tangle into a garbage bag and tossed it in a corner. A dozen of those bags followed me to L.A. when I moved there in 1988, and after a couple years I started cutting and paging those negs, which went into a couple bankers boxes that then moved from apartment to house to garage to attic over the next two decades. I began organizing them in 2008, and spent the winter of 2009 making electronic contact sheets; I edited throughout the summer, and started scanning individual frames in the fall, which was a six-month process. I revisit those contacts once a year, to see what I might’ve missed in my last run-through; just this June, I found three really great frames that are among my very favorites in this show.

During all that, I learned a lot about how my style and craft developed. Since I’m a photographer who tries to have a personal point-of-view—rather than just being an “objective” recorder of scenes and events—my contact sheets are always full of specific ideas about composition and light; when you walk through those contacts, you can see me trying to nail a very particular notion: a visual pun, an angle, a certain shadow, a subtext. But, in retrospect, most of those notions are nonsensical and too forced and not nearly as interesting as I thought they were at the time. Sometimes I actually get a little nauseous, inspecting my banal, past attempts to make a picture “happen.” But, mostly, its more humbling than humiliating: I see clearly how young I was then, how green in many ways. But it also makes me realize that I really did have a gift for a certain kind of picture—probably my only true gift—which was so fully-formed, right from the beginning, that all my technical failures and rookie blunders couldn’t compromise it. The poignant thing, for me, is that when I chose to become a “real” photojournalist at daily papers, I set aside that particular kind of picture—the one I was born to make—for five or six years, until the mid-‘90s. I’m happy to say, I began shooting that way again in maybe ’95, after I was established enough to take some risks—and,the funny thing is that’s what made my national reputation. Clearly, daily papers were finally ready for what I’d been doing ten years earlier, and then they celebrated that “new style.”

Z: How did you choose which photographs to characterize a now-historic moment in San Francisco’s history?

TA: The body of work is large and varied—way too varied for one coherent exhibition. The pictures that made it into “Gay San Francisco” are stylistically very coherent; it’s clear that they came from the same photographer, and that that photographer had a distinct point-of-view. And then I chose the pictures that were the very best in that category. So, this exhibition is more a tone-poem than a straight-line narrative.

Indeed, with two or three exceptions, all those pictures are made with wide lenses, fairly close to their subjects, using a strobe light as principal illumination. (In fact, those couple exceptions almost lost their place in the exhibition, because they were made with long lenses and available light.)

That style of photography is still in use today, but its heyday was the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, mostly in New York. The photographers who pioneered that look were seen as “aggressive” and “confrontational,” because their pictures were close-up and strobe-lit. Diane Arbus, William Klein and Garry Winogrand were certainly that, but other photographers used those techniques in a kinder and gentler way: Larry Fink, Lee Freidlander, Rosalind Soloman, Jeff Jacobsen, Mary Ellen Mark. It’s no coincidence that that latter group tended to work for magazines, in which there was a minimal obligation to illustrate stories with “sensible” pictures that included context and environment.

Reluctantly, I joined that second group. When I began developing my version of that pictorial style, as a student in Michigan, my natural inclination was to obscure and deconstruct the “assigned narrative” in a scene—to, in short, render the “story” indecipherable. But I soon realized that, in order to get access to the events I wanted to shoot, I needed to work for some kind of newspaper or magazine, which meant I had to deliver at least a handful of pictures that were coherent accompaniment to the written report. But I was still pretty insistent that the pictures have that “look”—the wide lens, the flash, the cockeyed angles—which disqualified me from regular work at daily papers. So, I spent five or six years working for weekly tabloids, where such pictures were not only tolerated but actually celebrated. The work I did at the Sentinel, in San Francisco, was definitely of a piece with the pictures that were being done at weeklies in New York, especially at the Village Voice, the granddaddy of them all. In later years, when I became a successful photojournalist at daily newspapers in Los Angeles, the pictures I made were far less personal and quirky and, in retrospect, far less “interesting” and memorable.

2 thoughts on “Documenting Life Amid the ‘Dragon’s Jaws’: Q&A with Thomas Alleman”