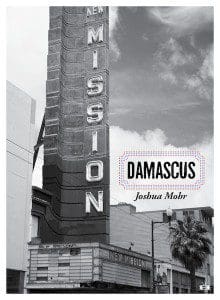

Critics have compared the writing of Joshua Mohr to that of Dostoevsky and Bukowski’s for the imagination with which he depicts grimy people clawing through a downward spiral. Following suit, Joshua Mohr’s third and most recent book, Damascus (Two Dollar Radio, 208 pages), rolls out a sooty cast of compelling characters including a Santa suit-wearing bartender, a memory haunted ex-Marine, a controversial performance artist looking to hit it big, and Shambles, “the patron saint of hand jobs.” They all struggle with emotional scars, addictions, and a litany of pathological neurosis. As in all three of Mohr’s books, what elevates Damascus from the mire of fatalism is its immense compassion. Readers can relate to Mohr’s characters, finding more than a sample of themselves in these seemingly broken people.

Meeting Mohr can be, like reading his books, a bit intimidating. (This is a man, after all, who wrote a scene in which an alcoholic tap dances barefoot on broken glass to keep from having a drink.) He’s six feet, his arms are tattooed; he has dark hair, stubble and penetrating eyes. Then he offers a warm hand and the ebullient conversation that follows dispels any discomfort. Mohr is quick to laugh, and though he mirrors his book’s dark humor and dry sarcasm, he’s sometimes goofy; for this interview with ZYZZYVA, he wore a Pepsi T-shirt in which “Jesus” replaced the brand name. We met in San Francisco’s Mission District at Ritual Coffee Roasters, a setting alluded to in Damascus, to talk about his work.

ZYZZYVA: In interviews, Robert Altman has partly defined his style as making the audience feel like a voyeur. You’ve mentioned that you wanted your third novel to read like an old Altman script from the seventies. For Damascus, were you consciously trying to reproduce the feeling of being a voyeur?

Joshua Mohr: The thing that all my books have in common is this really suffocating take on point of view. One of my goals is to really embed you into minds, really embed you into scenes you may not want to be a participant in. So from that standpoint, the voyeur only works up to a certain point, because one of the things that fiction has over filmmaking is that we are privy to what’s going on in people’s minds and what’s going on in people’s hearts, so we can actually take it a step further. Suddenly, we have not only the voyeuristic experience going on, but at the same time we also have our reader peering through the heart and peering through the brain of our players. So hopefully they’re able to experience it on this incredibly intimate and incredibly visceral level. When they become Shambles [a character in Damascus] jerking off a cancer patient in a bathroom, they probably don’t want to be that person. But if I’ve done my job right, they leave that scene, you know, probably needing to take some sort of literary shower.

Z: Well, I think your books are all wildly successful at having scenes that are extremely compelling but uncomfortable to be in. So congratulations.

JM: Well thank you. It’s nice to know that I can continue to alienate an audience, which is one of my ultimate goals.

[Laughter]

Z: You make rather explicit references to your characters’ internal lives through their physical defects. In your first novel, Some Things That Meant the World to Me, Rhonda has an unset broken arm. Mired, from Termite Parade, has broken teeth. And Owen in Damascus has that Hitler-esque birthmark on his upper lip.

JM: One of the rules I’ve set for myself when I decide that I want to externalize something on a character’s body, which is going to modify or map to who they are inside, is that I’m only allowing myself to do that based on things that I’ve actually seen. So I used to have an old neighbor who had fallen off a horse, this crazy old lady. She fell off a horse and broke her arm and never got it set and as she’d been aging over ten or fifteen years her arm has continued to bend. So when I knew her, it basically was shaped kind of like a capital C. It was this terrible, terrible thing. And every time you would ask her why she didn’t get it fixed she’d just be like, “Oh, what’s the point, I’ve lived with it this long,” so on and so forth. And it seemed like a perfect metaphor for addiction.

So now we’re starting to build some sort of composite psychology for what might work in Rhonda’s mind; this idea of “never finding the right way to solve what the real problem is,” really, I think, resonates with him as a player. Something as simple as going to the doctor and having your arm set — you know, if you’re programmed like a normal happy person, obviously you go get that arm set, but if you’re programmed like Rhonda is, that seems like the most uphill battle you could possibly imagine.

And in the second book, Termite Parade, I had a friend who I saw fall down drunk on the street and knock her teeth out. And it just seemed like an interesting way — even though I didn’t end up using that exact tableau — it seemed like an interesting metaphor that I could find a way to contort and use. And I saw a guy on MUNI one time with this weird mark between his nose and upper lip, and from a distance, with my terrible caustic attitude toward life in general, it looked like a Hitler mustache to me, and I just thought it was funny. So then I decided to try to use that as one of the driving character details in Damascus.

Z: All your novels have characters that are plainly in a state of personal apocalypse, with ambiguity surrounding whether or not they escape their self-destruction. But it also seems like each new book is more hopeful than the last, or at least less ambiguous about who escapes doom. Was that a conscious decision? Do you feel like you’re taking a more definitive stand on your characters’ ability to save themselves?

JM: There are probably two things happening that you’re noticing. The first one would be the more personal side of that, which would be that I’m sober now, and Damascus was the only book of these three books that I wrote not on booze and drugs the whole time. So I think my worldview is starting to morph a little bit. Whereas with these things [booze and drugs] we’re always kind of really monochromatic and really bleak, I think I see a much more colorful world around me now than I did back then. So if there is optimism in the third book that wasn’t there in the first two, it’s probably because there’s optimism in my heart that wasn’t there in the first two.

But in terms of just looking at the art as their own bodies of work and trying to separate myself out, if that’s even really possible, it was a conscious decision for me not to want to paint these characters into a really tight corner. I wanted there to be a little bit more ambiguity. When the book fades out on the last page, you could make a pretty cogent argument both ways. Maybe you could say, “I can point to these three pieces of evidence in the narrative that mean maybe she gets her shit together,” or “I could point to these three pieces of evidence in the narrative that she doesn’t.” A lot of that’s going to depend upon what the reader’s bringing to the book.

Z: Damascus has a little bit more political awareness than your other novels, almost to the point that you could argue it’s a polemic book.

Z: Damascus has a little bit more political awareness than your other novels, almost to the point that you could argue it’s a polemic book.

JM: Polemic meaning controversial?

Z: Well, in that it makes an argument about the war in Iraq or at least that it makes an argument as opposed to displaying people. It seems like a big shift from previous novels that had a very inward focus. This latest novel has a distinct outward focus, localized around a controversial art show about the Iraq war and the conflict between a group of angry soldiers and the artist. Do you agree? And was that a conscious choice?

JM: It was conscious in that I wanted to tell a very specific story. I don’t feel that I’m a smart enough a person to get on stage and wax about geopolitics. But I do feel I can talk about this one dive bar, Damascus, in this one neighborhood, in this one town, and I can use that setting as a microcosm to have both sides of the argument. Because it isn’t just an anti-war book, hopefully I present the soldier’s stance with as much dignity and as much integrity with which I presented the performance artist’s stance; at least that was my goal going into it. You would be allowed as a reader to say, I’m siding with character A or I’m siding with character B.

Z: Speaking of artists, there are artists in your novels who make questionably moral art. In Damascus, the artist is killing fish by hammering them to portraits of fallen soldiers, and in Termite Parade the artist is scaring unsuspecting people to catch their reactions on video. What are you trying to say about artists? Are you trying to say something about these particular artists, are you trying to engage in a dialogue with the larger artistic community? Or do you just find artists to be interesting characters?

JM: I think artists are always interested in the worlds of other artists, and I like to be able to masquerade in the different mediums. I think that, specifically, with the performance artist in Damascus, I’m having a bit of fun with her. When I was twenty-two, I might have seen what she was doing and thought it was pretty badass. I think at this point, I’m having a little bit of fun with the limits of … how to describe it? The limits of where art stops — or what’s an artist’s responsibility during wartime.

And it’s a really interesting thing to dialogue about in general: as artists, what are we supposed to do when our country is doing things we don’t agree with? We’re fighting these wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, are we supposed to just write Whole Foods realism stories about what happened to Patty’s kids after school today? Or do we have some obligation to try to document some of this stuff and try to make sense of all the chaos. So that was definitely going on for Damascus.

For Termite Parade, I was talking a lot about reality television without ever really wanting to mention that [the story] is a metaphor for reality television. I think that stuff is really interesting. Where do we set the boundaries? Do boundaries even exist anymore? What’s the difference between public versus private identity? But again, I didn’t ever want to get on my soapbox and wag my finger in everyone’s face about this is a big metaphor for reality TV. I think that connection’s there to be made, but it’s definitely quiet.

Z: So there was a different intention between putting an artist in Termite Parade versus Damascus?

JM: I think so. I mean, being an artist myself, I’m probably very narcissistically interested in the idea of what is the capacity for art to influence people. Especially as we hear about the desiccation of the attention span, that no one reads anymore — I mean, “insert artist’s complaint here.” I think it’s fair to stand back and just say if no one’s participating with our art, why do we continue to make it? What’s this gust, this wave that just propels us to keep making art despite evidence to the contrary? What keeps us getting up and making art?

Z: So what’s your answer to that?

JM: Well, I think on a fundamental level it’s just that idea of communication. I think that there’s always this susurration behind every page where you’re just telling another human being that you’re alive. I’m up here, I’m doing this, I hope you pick this book up and I hope it’s meaningful to you. I hope, even though we’ll probably never meet face to face, I hope this makes you feel something. Because I felt something while I was on this side of the equation putting the pieces together, and if we can find a way to connect, a way to feel, a way to yearn, I think that’s really important.

Z: In Damascus, you post your email address in the Acknowledgements, inviting the reader to contact you with their thoughts. This is also something you occasionally do on your website in your blog posts. Have you gotten any emails from readers? What kind of emails are you hoping to get?

JM: I like that idea of trying to reach out and communicate or humanize those things. For Termite Parade, I put a poll up on my website with five different pictures, asking people to help me pick which author photo to use in the book, and they all voted, and that was the one that I ended up using, even though the one where I had this awesome mustache would have been so much better.

And with Damascus, it’s just this idea of trying to invite people to join a dialogue. Whether in Twitter or some kind of ironic Facebook status, there can be a lot of one-way communication. But I want a way that you can invite people into an educated conversation, not where we’re just making snarky posts, where we’re having a clever competition with whoever we think is out there in cyberspace, but to actually engage, even if it’s virtual, in a one-on-one interaction. Everyone who sends me stuff, I always answer, whether it’s on Good Reads, Facebook or direct email.

Of my books, the one that I get the most interesting emails about is the first one [Some Things] because it’s such a naked story about a fucked up childhood. So many of us had really rocky, tumultuous experiences growing up, and I get emails from people all the time where they say, thanks for having the balls to write all that stuff down. There’s a scene in the book where the little boy’s house is described, where all the rooms are moving apart from one another like separating continents, and I got an email from a woman just last week where she said, “I grew up in a moving home, too.” Talk about an intimate connection. I would always rather hear something like that than “I thought your book was good,” which is a very static response. I mean, that’s cool, too, but when you can actually hear the really emotionally touched side and merge to someone’s own side of experiences, I think that’s really remarkable.

Z: You have some interesting marketing strategies for your books. For your first book, on your website, there’s images of you dressed up as some of your characters. For your second book, you did a preview movie video —

JM: Did you think I looked good as old lady Rhonda?

Z: Oh yeah, you were fabulous.

JM: I think I use her as my phone wallpaper. [He shows his phone. The backdrop of his phone is an image of him, dressed as a white-haired woman in a dress with a diving neckline.]

Z: Do you see that as part of the artistic wholeness of the book? Are they linked together, or are you just having fun with some marketing strategies?

JM: I think the more you can do to keep a sense of whimsy, not to take it too seriously … I don’t ever want to be the kind of writer who’s all elbow patches and monocles, you know, I want to have fun with the stuff. I take my job very seriously, I want to do a really good job at producing the best book I’m capable of producing, but at the end of the day, they’re just books. We’re not saving the children in Sudan, or working in Japan for disaster relief or whatever it might be. So I think it’s important that two things can be equally true, you want to write books and you want those to be the best books you can write, but to keep it in a comfortable frame of reference.

I have friends who think that their artwork is so important to what’s going on in the real world and I don’t necessarily agree with that. I think that being able to produce art in-and-of-itself is such a luxury, and I want to continue to convey a sense of playfulness and a sense of fun. I think it helps to take some of that stock image of the pretentious author out of the equation.

Z: You’ve referred to your three novels as a cycle or trilogy. Does that mean your next novel will be a departure from this world? Are you planning to change things stylistically or thematically?

JM: Now that I’ve gone sober, I’m very much not interested in writing about alcoholics anymore. I’m ready to put this stuff to rest. It was a fun world to spend a lot of time in, but it was also an exhausting world. It never really occurred to me why it took me so long to write these books. Like Damascus, specifically, I’ve been working on for seven years, and I think it’s because it was so personal that I have to take a lot of time off in between drafts just to put some fucking calluses back on my body before I get back into that really painful ecosystem.

With this new thing I’m writing now, I’m working on this crazy postmodern fairy tale that has nothing to do with anything that I’ve ever really experienced. I wrote it to be comedy, which is something that sort of makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up even just saying that out loud, it makes me really uncomfortable. There’s something almost safe about the nihilism and fatalism present in these first three books, and now telling this over-the-top fairy tale, I feel incredibly vulnerable and incredibly exposed in a way I haven’t really anticipated feeling. It’s pushing my buttons, but hopefully it’s also pushing me to make better art. We’ll see if that works out or not, but anyway, I’ve been having a lot of fun being completely fictional. Whether or not that ends up bearing fruit, it’s too early to tell.